I recently finished the latest season of Dancing With the Stars. For those who weren’t keeping up, Robert Irwin and his professional ballroom partner, Witney Carson, brought home the highly coveted Mirrorball trophy.

Every year, a new season of this show premieres, and it becomes one of the only things I can talk about and the thing I look forward to the most on Tuesday evenings. This year, I was rooting for Whitney Leavitt from The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives. Sadly, I couldn’t text “WHITNEY” to 21523 because voting is only available to the United States and Canada, and I’m in… Scotland. But I was supporting her from afar!

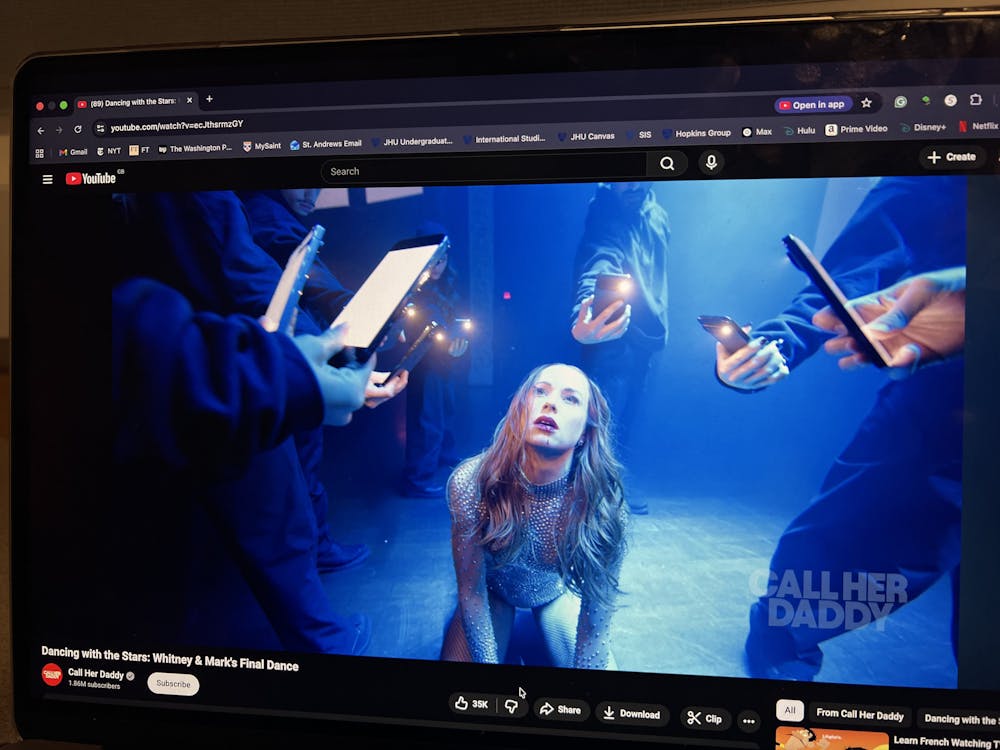

In case Reality TV isn’t your forte, or you decided to skip this season of Dancing With the Stars, Leavitt was eliminated during the semi-finals due to a lack of fans voting for her to stay in the competition. The third season of The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives had aired right before the semi-finals, and to say it hadn’t been to Leavitt’s benefit would be an understatement. But this was the first time I had seen a vast number of people on social media band together and actively decide to vote for every other couple except her (I think psychologists call this groupthink).

While I am not one to lecture people on the dangers of obsessing over Reality TV or developing a black-and-white form of thinking, I had never quite seen how social media could be wielded as a destructive tool in real time.

Naturally, as a Political Science student, I began to think about how easy it has become for our society to succumb to dangerous forms of thinking — seeing things not on a spectrum, but as either all-or-nothing. We’ve already begun to see this mentality infiltrate our politics.

The recent government shutdown, the longest in U.S. history, serves as a prime example — Congressional Republicans largely refused to compromise with Democrats on a spending budget and vice versa. Throughout the entire shutdown, I would see comments on TikTok or Instagram either blaming Democrats for the shutdown entirely or insisting Republicans were single-handedly responsible for the stalemate. Very few people seemed willing to admit what political scientists seem to repeat like a broken record: that a gridlock is rarely the fault of one person or party, but rather the product of institutional incentives, polarized media ecosystems and elected officials who ultimately benefit from refusing to budge.

But that kind of nuance doesn’t trend.

What does trend, however, are the posts that declare “This side is evil” or “That side ruined everything.” Social media rewards outrage, certainty and villians to point at, because life is always a little easier when you have someone else to blame. And once the algorithm finds the narrative you’re most likely to engage with, it feeds it back to you until your entire worldview feels confirmed — no matter how distorted it becomes.

This is how we get from voting against a contestant on Dancing With the Stars because TikTok told us she’s “problematic” and a “horrible person” (when most of us don’t really know her at all), to voters insisting that one political party alone is responsible for government dysfunction. It’s the same impulse dressed up in different stakes: we want someone to blame, someone to cancel, someone to remove, so we don’t have to wrestle with complexity.

And the political system thrives on this. Politicians don’t get reelected if they make things complicated for their constituency. They know that if they provide a simple enemy — a person, a party, a scapegoat — social media will do the rest of the work for them. Outrage spreads faster than any policy briefing ever could.

In the end, maybe the real Mirrorball trophy goes to the platforms themselves. They’ve mastered the art of choreographing our attention, pushing us into neat little corners where the world makes sense only if there’s a hero and a villain, a winner and a loser, a right and a wrong. No shades of gray and definitely no middle ground.

But politics — like people, like ballroom dance — has always lived in the in-between: the messy, complicated, imperfect spaces where the real work actually happens. We need to dive into the nitty-gritty and actually understand what is going on. Or else we risk becoming victims of the very system we claim we want to fix.

If we want a healthier political culture, maybe the first step is learning to log off once in a while and touch some grass. Remember that not every conflict needs a villain. It takes more energy to think about nuances and retrain yourself to look at the shades of gray, but it’s worth it.

Sometimes it’s a controversial semi-final round of Dancing With the Stars, a broken Congress or a system that needs more cooperation and less choreography.

And unfortunately, you can’t fix all that by texting “WHITNEY” to 21523.

Alyssa Gonzalez is a junior majoring in Political Science and International Studies. Her column approaches the political atmosphere through an individual lens, grounding the conversation in empathy and clarity in an attempt to humanize the field.