I used to think closeness was a grade I had to earn. If I were easy, uncomplaining, funny on demand and bent to their interests, then friends would keep me. On bad days, I'd check notifications as if they were emergencies. On good days I told myself I didn’t need anyone at all. Between those two postures, constantly anxious or apathetic, was a yearning: I wanted to feel safe with people, and I wanted to feel safe with myself.

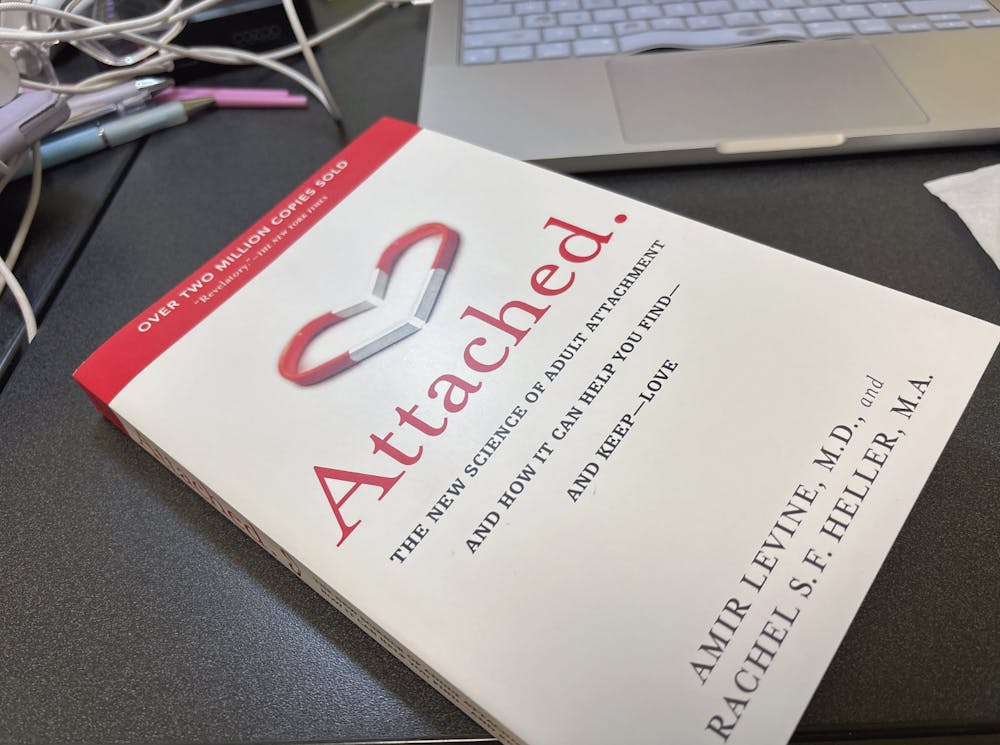

I started reading Attached by Amir Levine and Rachel Heller. They describe three attachment styles: secure, anxious and avoidant. It’s mostly discussed in the context of dating, but I started seeing these patterns long before I recognized them on any first date. I’ve seen myself in the midst of all three. The anxious parts of me show up as a quick scan for signs: Did that “okay” sound annoyed? Have they been responding slower? And then I have the urge to fix whatever I imagined I had broken. The avoidant parts show up as a quick, polite escape into “I have to go to my class.” And the secure voice, when I can hear it, tells me that nothing catastrophic is happening.

The book traces these styles to early experiences; how our needs were noticed or missed as children often shows up later in our lives. It explains so much to me, why silence sometimes feels louder than it should and why certain tones reassure me and others do the opposite. Levine and Heller are just as clear that these styles aren’t destiny. We are not defined by them — they’re just what we relate to, and we can work to outgrow them.

Somewhere along the way I confused emotional support with validation. I wanted people to encourage me, but I also wanted them to define me: tell me I’m kind, driven, smart, in perfect control of everything I do. Say it until I believe it. The problem is that compliments evaporate when they’re covering a hole only I can patch. I can and should seek emotional support from others, and I’m not built to do it alone. But my core confidence, knowing who I am when no one is clapping, can’t be outsourced. When I treat the people I love as proof of my worth, I stop relating to them as people and start performing for them. It’s exhausting for all of us.

Attached calls this the dependency paradox: when our needs are predictably met, we don’t become clingier. Depending on trustworthy people makes us more independent, not less. I’ve seen it in small ways. Receiving a comforting text such as “I’ve got a lot on my plate, taking a rain check” keeps my brain from inventing anxious scenarios. And it goes both ways. When I answer consistently, I become someone else’s soft place to land. That’s what healthy dependence looks like.

Of course, these habits still come up from time to time. I want to triple text, apologize for existing and call it “communication.” But I want to be able to describe how I’m feeling without depreciating my own self-worth or disrespecting the other person. Family is trickier. The same people who taught us our first attachment lessons are the ones we’re trying to re-learn with. I don’t expect a family group chat to transform into a therapy circle, but I do think we can change how we show up.

What I keep returning to is permission. Not just permission to feel, but permission to need and to stay. To let people in without asking them to carry my whole identity. To receive reassurance without making it a condition for existing. To be the friend who replies, the sibling who calls, while holding my own center when I receive responses that are imperfect and human.

Maybe that’s what security really is — being with people without dissolving into them and being yourself without pushing everyone away. On campus, at home, in all the spaces in between, it looks ordinary — answering texts, showing up when you said you would, saying “I need a minute” without disappearing. And in that balance, closeness stops being a test I’m destined to fail and starts feeling like a place I can rest and still be myself.

Linda Huang is a sophomore from Rockville, Md. majoring in Biomedical Engineering. Her column celebrates growth and emotions that define young adulthood, inviting readers to live authentically.