I have never experienced unadulterated joy like my first listen to Sam “King of Soul” Cooke’s 1963 epic, his album Live at the Harlem Square Club. Hidden beneath a steadily strumming upright bassline and lightly up-tempo drum swing, Cooke’s masterful crowd work combines with a raucous, enraptured audience to create one of the most magical 36-minute sets I’ve ever heard. It’s the kind of music that makes you want to roll your windows down on a quiet summer night, the type of songs that find a way to penetrate a bad mood with a specific kind of impossible-to-ignore, jumping-up-and-down passion.

In lyrical simplicity, soul music captures the essence of everything that is so keenly right in the world. It transcends chords, strings and vocals to evoke some higher power. Cooke’s high-pitched rhythmic scream, heard on the outro to “Having a Party” epitomizes the nearly religious atmosphere cultivated by the short but memorable concert. There was extraordinarily little room for interpretation within the four walls of Harlem Square, which is the beauty of it all. Cooke’s words ignited a fire in a world that was so clearly rigged against him, one that was eager for him to fail.

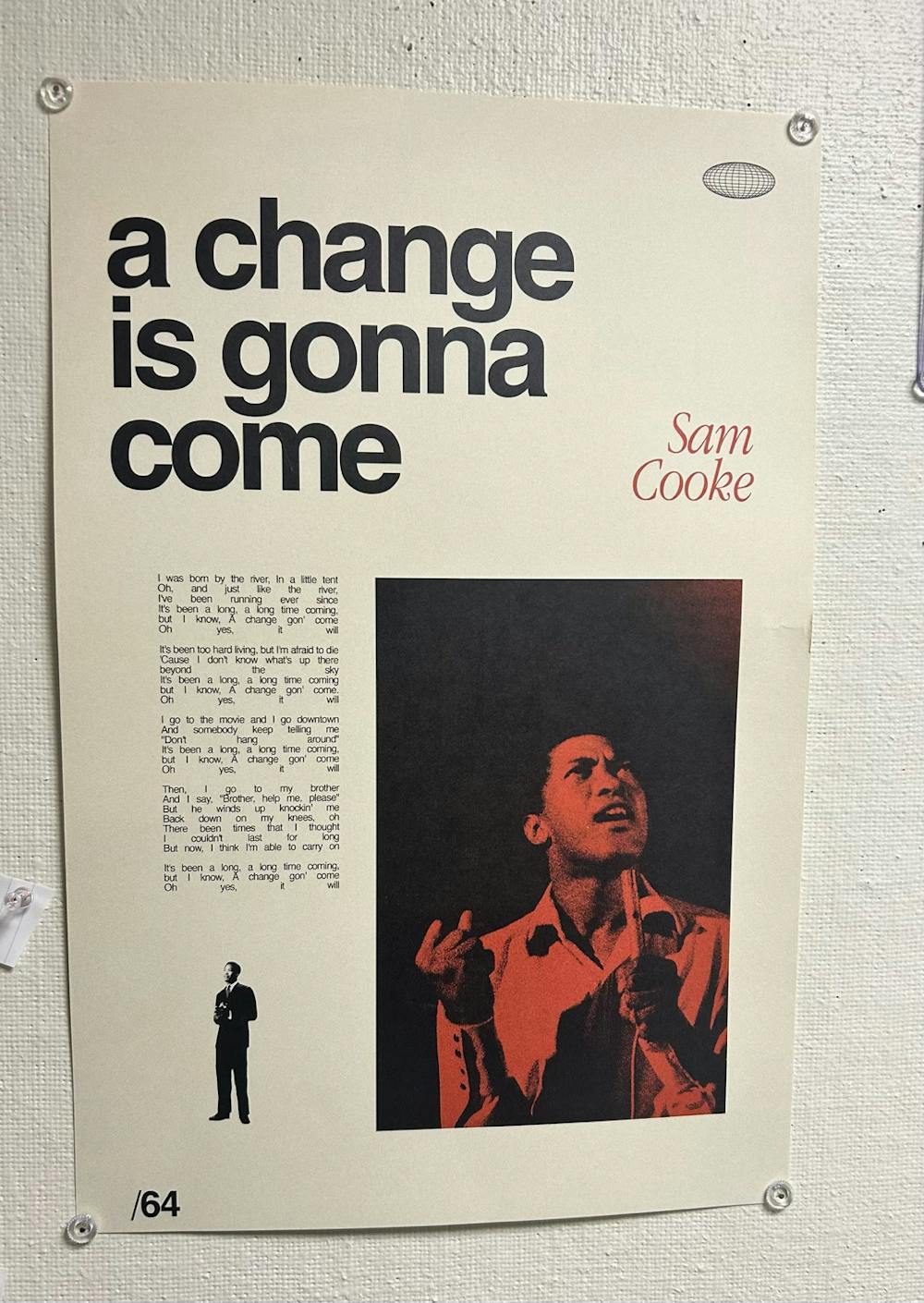

An activist for the Civil Rights Movement, Cooke shared societal and personal struggles through “Chain Gang” and “Bring it on Home to Me.” His music was a triumphant display of authenticity at a time when racism was a prevalent worldview in America.

Cooke’s sincere craft shines above all; his unfeigned truthfulness to himself is what managed to reach me decades after his performance. As unorthodox as it sounds, soul music has saved me more than once during my time at Hopkins. Arriving on campus in mid-August was supposed to be a flood to the senses — like a moon-landing onto some foreign planet. The impersonal, packed Rec triumphantly showcased double the number of people who attended my high school, and the expectant smiles of people I hadn’t yet met left me with a dully sour taste in my mouth. I couldn’t quite swallow the fact that Homewood didn’t feel like my home, and these people didn’t seem quite like the friends I grew up with.

I walked around my new double room with the silent acknowledgement that I wouldn’t go home until Thanksgiving, and that didn’t hurt. The weight of distance didn’t overwhelm me, and it certainly didn’t bring joy; a silent cognizance of my new life was vacancy, not acceptance. That is, until I lay out on my twin XL bed, toes comfortably touching the footboard, put my headphones on and closed my eyes.

I’m immediately transported to a homey, neon-lit nightclub in Miami’s Overton neighborhood, with a very much alive Sam Cooke urging me, “Don’t fight it, just feel it.” He lets the music overtake him, the rush of the ensemble enveloping the crowd in waves. It’s almost difficult to see him as the air grows thick with smoke, a grayish haze covering the pit before the gospel-inspired “Soul Twist” generates a foot-stomping singalong. For just a moment, I’m able to let the doubt and otherness wash over me, and I wallow in the singular aloneness of starting a new life 300 miles from my old one. Cooke grants me unspoken permission to grieve, to allow sadness.

Enduring pain doesn’t have to be a negative experience. I know that I’d rather feel lost than feel nothing at all.

A little over half an hour later, I gently press a button on the side of my head, making a silent but graceful exit with what I’d like to think is a knowing nod between a civil rights icon and a white guy from Connecticut. Snapping back into reality through the buzz of the AC unit, my eyes move from the painted white brick slowly toward my in-need-of-a-vacuum floor. Pinpricks on the canvas wall are thumbtack-sized tributes to the singers, movies and people that have shaped those who lived before me. The fluorescent lights of a college dorm room are a brutal contrast to the lowlights of a jazz club, but I’ll manage.

Putting my feet on the carpeted ground again, my next step is not confident but aware. I don’t know where they’ll take me, but it’s hard to be despondent with a voice in my ear singing:

It’s alright

It’s alright

Believe me when I say it’s alright

Long as I know, long as I know that you love me

Baby, it's all right

Bryce Leiberman is a freshman studying Political Science and Philosophy from Madison, Conn.