It’s not that I’m ashamed of being Vietnamese — now at least. Growing up was a different story. I really don’t want to frame this piece like another “I grew up in a predominantly white area and I had no one that looked like me,” because that’s not real.

The truth is, I did grow up in a predominantly white area (Pensacola, Fla. is as Deep South as you can get), but there were plenty of Vietnamese families. There were small clusters that knew each other through church or food or gossip, but I was never really part of that. My parents didn’t go to community events (they are anti-friendships), and I never learned how to properly say “hello” to people in Vietnamese without feeling like I was performing.

I told myself it was because I didn’t like the noise, how everyone was conservative and the way the adults would compare kids’ grades like it was a sport. But, really, it was because I didn’t want to be the wrong kind of Vietnamese (the one who didn’t belong even among her own).

The truth is, my shame is about disappointment. The people who were supposed to understand me best were the ones who made me feel small: the elders who whispered about how dark my skin got in the summer, the kids who made fun of how I couldn’t read Vietnamese, who rolled their eyes when I said I didn’t go to church. Even as a child, I knew that kind of judgment wasn’t about culture but hierarchy. Who is more Vietnamese? Who is more American?

I never knew how to balance the two, and after a while, I stopped trying. It’s strange, the way that resentment hides as indifference. For a long time, I told myself I didn’t care. That I didn’t need a community, didn’t need people who shared my face or my language. But sometimes, when I’d go to a Vietnamese restaurant and order food, a waiter would smile and my heart would sink before I could stop it.

There was always that flicker of recognition that was followed by guilt for wanting it, and then shame for never knowing how to reach for it. I was too liberal for the South, too dark or too light to be considered the “right kind” of Asian and too American to be the right kind of Vietnamese.

That didn’t change when I got to college. At Hopkins, everyone has their group. The East Asians and the South Asians are two huge communities that move in clusters, and I don’t fit into either. The Vietnamese people I do meet are scattered, and even then, it feels like we’re trying too hard not to cling to one another, afraid that doing so might reveal how unsure we are about what connects us.

When people ask me where I’m from, I say Florida before I say Vietnam. When they ask me what kind of Asian I am, I hesitate before answering, because I’ve learned that “Vietnamese” doesn’t mean much to most people.

Sometimes I think about writing about being Vietnamese, but my words don’t come out right. I look at Voices articles like Steve’s “The first time my Chinese was good enough” or Magazine articles like Buse’s “I wouldn't be me without my Turkish idioms”, and I freeze. Their pieces are homecomings, while mine would’ve just sounded like an apology. I don’t have a clean narrative or a triumphant rediscovery of identity. I just have fragments: the smell of fish sauce clinging to my clothes, the sound of my parents speaking in half-English, half-Vietnamese and the ache of wanting to belong to something that never quite wanted me back.

The hardest part is admitting that I’ve built my own bias — that I’ve spent years rolling my eyes at the Vietnamese conservatives who hung MAGA flags outside of nail salons and cringing at the whitewashed Vietnamese kids who can’t differentiate between spring rolls and egg rolls. I told myself that I was different, but that was just another way of keeping distance.

But I want to be proud. I want to be proud that I speak a second language. I want to be proud of the food, the history, the way Vietnamese people carry humor through grief like a lifeline. I love my culture, even when I don’t feel seen in it.

I think that the biggest part of my hesitation is the fear of being misunderstood, not by my white readers but by Vietnamese ones. I’m scared that they’ll think I’m ungrateful, that the American ones will feel like I’ve turned my back on opportunity, while the ones from Vietnam would suppose that I’m too soft and Western to understand what being Vietnamese really means. I’m scared that they’ll see this as another daughter of diaspora talking too loudly about things that should be kept quiet.

And so I push away being Vietnamese. Instead, I told the world: I’m a writer, I’m a student, I’m an editor, I’m a researcher.

But I know deep down that before all of that, I am Kaylee Nguyen.

I’m still learning what that means, how to hold pride and love myself, though I do know that I want to be happy with who I am. Maybe that’s why I don’t write about being Vietnamese, it’s because I’m still learning how to love the parts of myself that make me flinch.

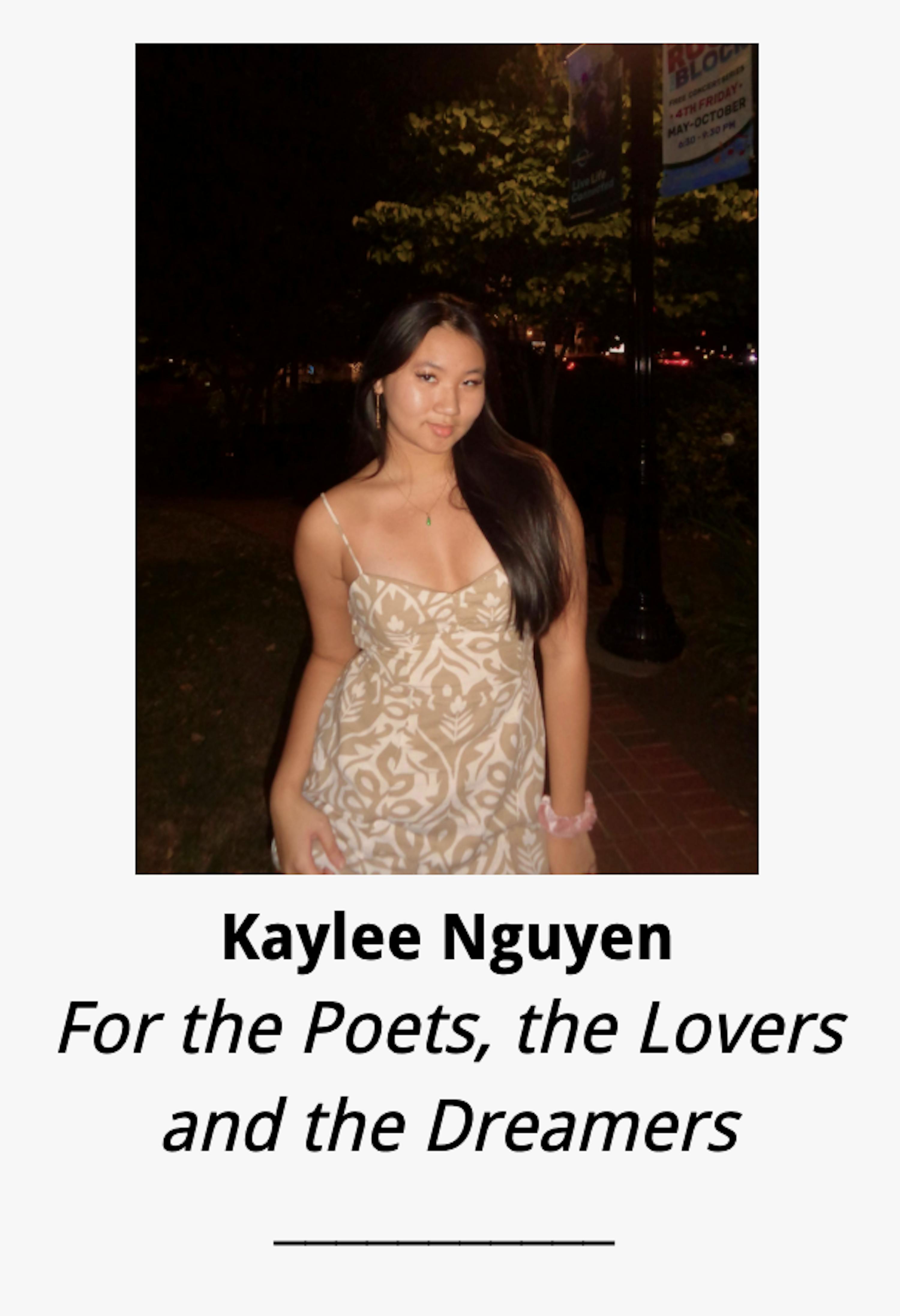

Kaylee Nguyen is a sophomore from Pensacola, Fla., studying Molecular and Cellular Biology and Writing Seminars. She is a News & Features Editor for The News-Letter. Her column tackles how creativity connects with identity as she hopes to connect with others through shared experiences and the universal love for learning.