On Thursday, Oct. 9 the Opioid Industry Documents Archive (OIDA) hosted a Q&A with Christopher K. Haddock and Andrew Kolodny about their team’s recent publication: “Imagine the Possibilities Pain Coalition and Opioid Marketing to Veterans: Lessons for Military and Veterans Healthcare.” OIDA, which is co-created by Hopkins and University of California, San Francisco, won the Society of American Archivists Archival Innovation Award.

Haddock is the chief scientific officer for the National Development and Research Institutes (NDRI-USA). As a military veteran himself and a provider for a chronic pain program at a military treatment facility, he has first-hand encountered the effects of opioid addiction around him. Joined with Kolodny, the medical director of the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University, Haddock focused on the impact of pharmaceutical marketing on the opioid crisis with military veterans.They used OIDA to locate documents, identify the epidemic’s root causes and analyze corporate behavior harming public health.

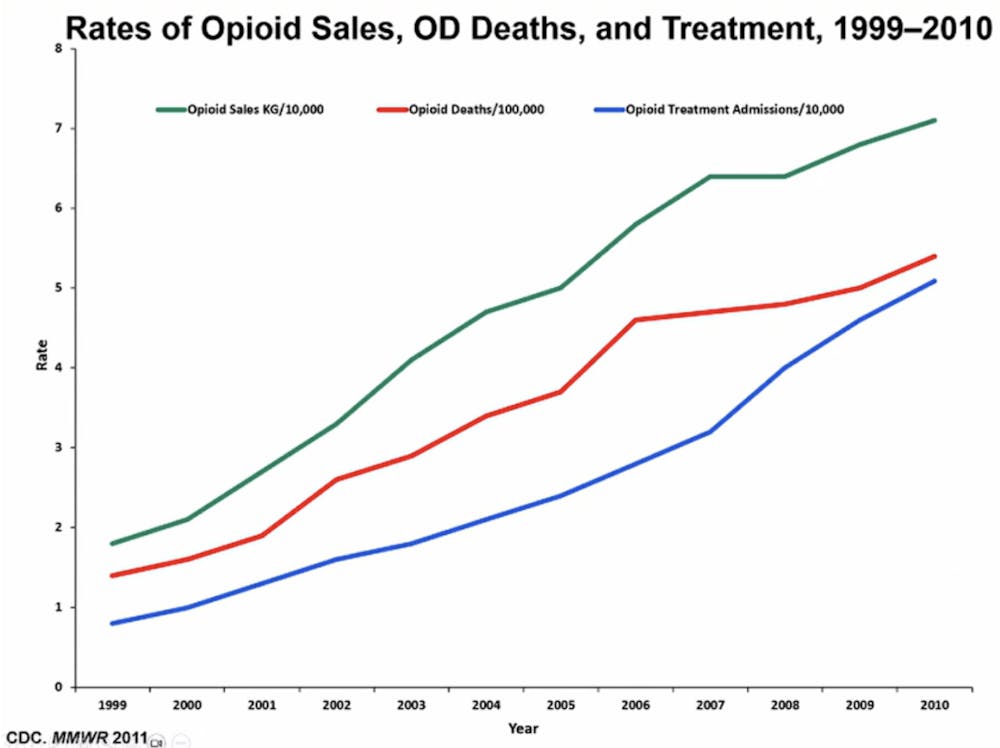

The opioid epidemic disproportionately affects veterans, with nearly double the mortality rate compared to the general population. Around 2011, the Center For Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began to regard opioid addiction as a serious issue and wanted to cut back on sales, but were met with major backlash from the pharmaceutical industry. Haddock and Kolodny focused on the example of the Imagine the Possibilities Pain Coalition (IPPC), a coalition run by Janssen Pharmaceuticals (now Johnson & Johnson).

“The IPPC launched in 2011 with a mission to create a broad-based community in the field of pain management focused on influencing the pain narrative to be person-with-pain centered, and, therefore, more holistically managed,” Haddock explained.

IPPC used many key tactics to promote their views to physicians and patients, including educational materials, such as publications, that overstated the benefits of treatment. Haddock claimed that similar tactics were also used by the tobacco industry. He emphasized the tactic on empathy-forward messaging, which aimed to normalize treatment with opioids. Haddock later highlighted the risk stratification, specifically the rhetoric that suggests harms can be managed later on in therapy, such as the idea that patients who become addicted to opioid can be treated after. Emphasis was placed on the pain veterans were going through at the present moment, not the harmful effects they may encounter down the line.

“Getting physicians to focus on the fact that the person in front of them has acute pain – has pain right now – and that their primary task is to solve the pain problem right now. So it was to try to remove the focus from anything beyond right now,” he stated.

Another tactic used by IPPC was ghostwriting publications to push positive narratives in scientific literature. One such paper investigated in Haddock and Kolodny’s research was “Pain management strategies and lessons from the military: A narrative review.” The paper drew lessons from military pain management, claiming opioids were successful for the military in pain management for veterans. They were framed as “critical” for those in chronic pain, and again emphasized risk stratification and that any addiction effects can be treated with therapy. This report had editorial support for manuscript preparation from MedErgy and was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. According to Haddock, since MedErgy was funded by Janssen, the company had major control over the paper and its publication. Another issue with the report was its citations. Haddock and Kolodny’s team discovered that the narrative review had displayed the citations out of context in a way that supported long-term use.

Haddock went on to explain the implications of these results for the Departments of Defense and Veteran Affairs (VA). Most importantly, it calls on them to investigate industry-funded “coalitions” to avoid strong influence over treatment, and prioritize evidence-based, transparent manuscripts.

“The opioid crisis [is] a very good example of what can go wrong when the pharmaceutical industry has undue influence on the medical practice. These are industries that remain not adequately regulated to this day and it really speaks to why the OIDA is so important and why research on these tactics is so important, because we really have to address these regulatory failures,” Kolodny concluded.

Kolodny and Haddock then moved into a Q&A session with viewers, moderated by Dan Kabella, a postdoctoral fellow with the OIDA at the University of California, San Francisco's Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education. Viewers anonymously submitted questions through the Zoom chat.

A viewer questioned if the system has improved throughout the years and if veterans were still being overprescribed opioids today. Both Haddock and Kolodny agreed that the circumstances have greatly improved. Kolodny even claimed that the VA guideline system is now one of the best in the country, even ahead of the CDC. However, he went on to say that there are still room for improvements.

“We are still prescribing opioids too aggressively for acute pain, both while they're in a hospital bed and on discharge. And I think we could be doing a lot better on that front and I think there is still room for improvement there within the VA system,” he said.

Kolodny and Haddock continue to emphasize the need for oversight on coalitions that emerge such as the IPPC. Haddock reaffirms that the fake empathy by companies is causing much hardship to consumers. By using “trojan horse marketing” (appearing to be patient-centered, but actually serving the industry), the pharmaceutical industry has hurt the lives of many veterans, and he believes such a serious occurrence should not be allowed to happen again.