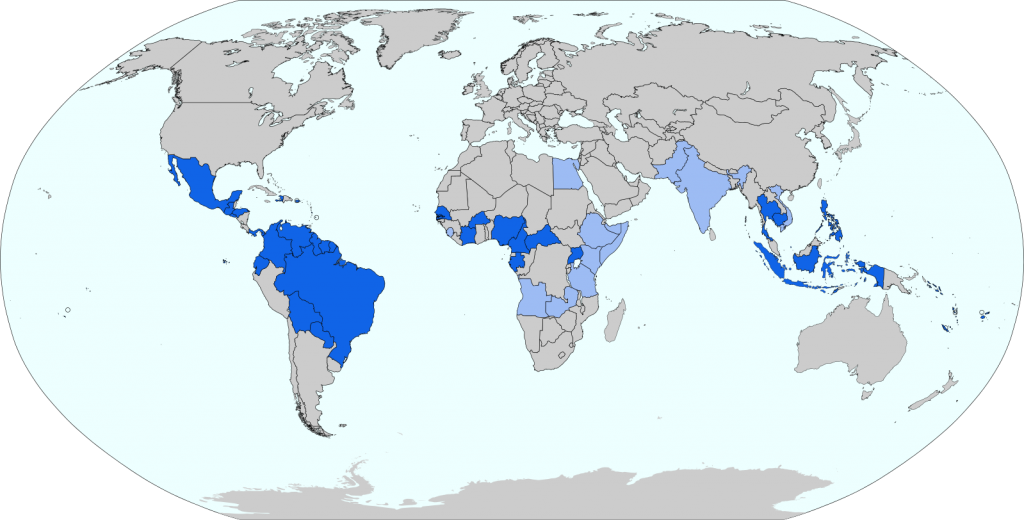

The current Zika outbreak has spread to more than 20 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that it will infect another four million people by the year’s end.

In response to the increasing number of Zika infections, the WHO announced on Monday that the current outbreak is a global health emergency. This declaration is expected to engender international coordination in the efforts to combat the disease.

Zika, a mosquito-borne disease, had not previously been regarded as a major threat due to its usually mild symptoms, which include a fever, rash, conjunctivitis and muscle pain. Zika rarely drives infected individuals to hospitalization. However, the scope of the affected population for this outbreak, as well as the recent spike in microcephaly cases, has alerted health and government officials of the need to sound an alarm. Microcephaly is a birth defect that results in infants who have abnormally small heads and may face a range of developmental and intellectual problems due to incomplete brain development.

While researchers have yet to establish Zika as the main cause of microcephaly, officials of El Salvador have urged women to delay pregnancy until 2018, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended that pregnant women avoid travel to affected countries. As for pregnant women who are returning from countries in which Zika virus is prevalent, the CDC urges that they consult a healthcare provider upon their return. Pregnant women who develop symptoms of Zika infection are also recommended to undergo a diagnostic test for the virus.

In addition to the lack of a vaccine for Zika, there is, as of yet, no reliable diagnostic test that can easily determine whether an individual is infected with Zika. Antibody tests for Zika may cross-react with those for dengue and yellow fever, so patients suspected of a Zika infection can only receive a definitive diagnosis following the detection of the virus in their blood or tissue samples at advanced laboratories.

The WHO, in response to the difficulties in managing the Zika outbreak with the currently available tools and knowledge, is leading the effort to control the Zika outbreak by strengthening the ability of laboratories to detect the virus, training doctors on the clinical management of Zika and emphasizing research into the Zika virus disease.

In addition to being associated with microcephaly, the Zika virus has been linked to Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) in some cases. GBS is a neurological disorder in which an affected individual’s own immune system damages nerve cells, causing muscle weakness and, in some cases, paralysis.

The exact nature of the association between the Zika infection and GBS is unclear, but the Brazil Ministry of Health’s reports of the increased number of people afflicted with GBS have caused both the WHO and the CDC to begin to spearhead research studies into the connection between the two diseases.

As the WHO and CDC continue their efforts in research, the WHO recommends that for the purpose of prevention and control of the Zika virus, citizens and travelers in affected countries wear insect repellents and stay in screened or air-conditioned rooms for protection against mosquito bites. The Zika virus is primarily spread by mosquitoes of the Aedes genus, which, after feeding on infected individuals, transmit the virus via bites to other people.

Local transmission of the Zika virus has recently been observed on the continental U.S., in a case of transmission via sexual contact, as travelers returning from affected countries have begun to import the Zika virus. While U.S. officials do not believe that there is a high chance of a Zika outbreak in the U.S., there is a prevailing concern that an international gathering, such as the one expected for the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, would spur the further transmission of the disease to spectators, who would then return to home countries which would have a greater mosquito population in the summer heat.

Though the colder temperatures that are predicted in August in Rio de Janeiro are expected to decrease the activity of the Aedes mosquitoes, some Brazilian virologists insist that merely eliminating stagnant water on Olympic venues would not be sufficient to ensure the containment of the Zika virus. Mosquitoes of the Aedes genus, particularly the Aedes aegypti, the principal transmission vector, are aggressive daytime biters that can breed in pools of stagnant water as small as a bottle cap. Moreover, as Rio de Janeiro is a tropical city, there is speculation that the mosquito population would be capable of transmitting the Zika virus year-round.

In addition to research concerning the association of the Zika virus to microcephaly and GBS, further research would be required to assess whether an international gathering such as the Olympics would present further complications in the containment of the Zika virus.