Some people move through life like it’s a test they didn’t study for. They try hard (harder than anyone sees) to be kind, to be useful, to be good. But beneath the polished surface, there’s a quiet ache. Not the kind that cries out, just a hum of sadness that settles in the bones.

Dorothy Rowe, a psychologist who spent her life listening to suffering, once offered a strange idea: only good people get depressed. Not the cruel. Not the indifferent. But the gentle ones — the ones who carry the weight of the world in silence, who would rather shatter inward than let anyone else break.

They are the people who still show up for others, even when they can’t get out of bed themselves. The ones who ask how are you? and really mean it — while quietly drowning in their own pain. And most of the time, no one notices. Or if they do, they don't understand. Because these people have learned to wear their suffering like armor: polished, quiet, invisible.

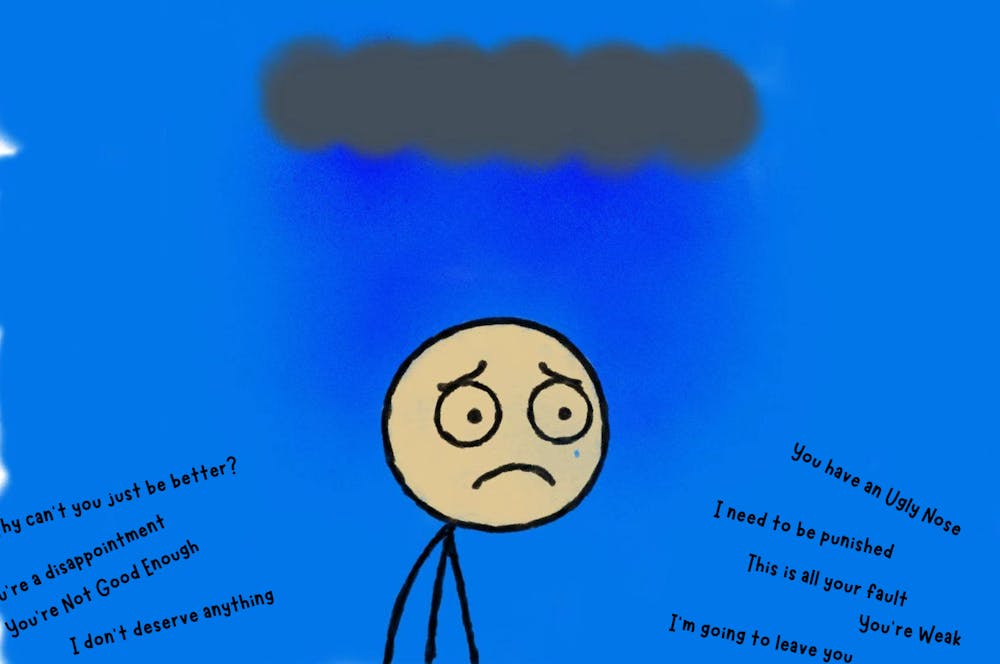

It’s not goodness in a moral sense. It’s something deeper — an aching responsibility. The belief that every wrong thing must somehow be their fault. That if they were just more capable, successful, perfect, the pain would go away.

They build their sense of self out of reflections and rules. Be helpful. Be strong. Be whatever keeps you loved. And so, when something breaks (a job, a relationship, a dream) it doesn’t feel like something is wrong. It feels like they are.

Rowe described this as a kind of collapse. Depression isn’t weakness, she said. It’s a defense. A structure the mind builds when it’s collapsing under the weight of its own expectations. A person wakes up and can’t move — not because they’ve given up, but because they’ve been holding everything up for far too long.

Behind this collapse is a story. A story they started telling themselves long ago: If I am not good, I will not be loved. And over time, that story became law. A prison, Rowe called it — constructed from beliefs that once protected them but now keep them small.

I must be perfect to matter.

I must never show weakness.

If I suffer, it’s because I deserve to.

These thoughts sound like shame, but they’re really survival. A way to make sense of chaos. If the world feels cruel, it’s easier to believe the cruelty is deserved than to admit it might be random. If love is conditional, it’s safer to believe it must be earned.

So they keep trying. Smiling. Achieving. Helping others. Apologizing for their own existence. And all the while, aching to be seen — not for what they do, but for who they are.

What Rowe offered wasn’t just theory — it was a kind of grace. She knew that the world rewards performance, not vulnerability. That it builds people up only to let them fall. And she knew that healing doesn’t come from fixing the self, but from releasing it — from rewriting the old, punishing stories.

A person cannot outrun their sadness by becoming better. They can only be free by becoming real — by letting go of the illusion that worth must be earned, that love must be proven.

Rowe reminds us: Depression is not a flaw. It’s a signal. A quiet cry from a heart that has tried too hard for too long.

And if only good people get depressed, then maybe (just maybe) that pain is proof of something quietly beautiful: the capacity to care, even when no one sees. Even when no one understands.

Leo Lin is a freshman from Xiamen, Fujian, China studying in History and Philosophy.