Growing up on the outskirts of Washington D.C., one of my favorite spots as a child was a bridge near my house that overlooked the trains rushing to and from our nation’s capital. Watching them with my grandparents was exciting for a five-year-old whose television habits involved Thomas the Tank Engine, Cars and other animated shows starring transportation. And so, my interests as a five-year-old included playing with a train set that I had at home, consciously observing bus and rail services, and reading books about our nation’s infrastructure and locomotives.

However, that interest took a back seat when I became inundated by the “cool” factor of space exploration and computer science, and my interests in trains and buses faded away almost entirely.

My high school commute was atypical for a student in the Washington Metropolitan Area. I didn’t take a car to campus and didn’t have a license either. My parents often worked long hours that prevented them from bringing me to and from my school, extracurriculars and home. The only solution? Public transportation.

Simply put, my commute to and from my extracurriculars was hectic. Often, it involved multiple modes of transportation: the Metrorail; my county’s bus service, Ride On; D.C.’s Metrobus; and the Bethesda Circulator, a regional shuttle service. However, navigating these systems as a high school student was challenging, as I had to be conscious of where and how these services operated. Living on the outskirts of D.C. exposed me to various roads, bridges and other map features, and, as a result, I developed a strong sense of direction. Accordingly, at first, I thought I was capable of getting around independently. I couldn’t have been more wrong. The bus and rail systems had conditions and nuances that made commuting more difficult than it needed to be. What were peak and off-peak times? If any, what were the cost savings involved in transferring between services? What was the express service, and did students have to pay? These were all questions I had to ask myself because failure to understand them would result in both the lengthening of my commute by a significant amount of time and a sharp increase in the amount of money I had to spend.

Ultimately, my daily commutes resulted in my growing comprehension of the design choices involved with transportation infrastructure. Peak and off-peak times were designed to manage the influx of people during rush hour, and their respective prices were adjusted to maximize revenue stream. Transfer discounts were designed to encourage people to use buses rather than their cars. Express services were designed to supplement existing lines by providing riders an alternative to get to places quicker, sometimes at a premium.

Further, my fascination with political science encouraged me to understand the planning and funding of these services on a government level. Downtime while riding public transportation often meant reading articles about designs for new infrastructure services, the bickering involved with financing and route planning, and the efforts by regional leaders trying to make infrastructure more accessible to low-income populations, especially during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Suffice to say, there are a lot of factors that go into transportation from an engineering and socioeconomic perspective, many of which I was completely unaware of before being immersed in D.C.’s public transportation systems.

Fast forward to when the pandemic hit. I no longer had the opportunity to take the bus and train. However, as a high school senior with nothing to do, I decided to take up biking, a hobby I’ve written about previously. That was when I encountered a piece of transportation that we often overlook: bike trails and foot trails. Bike trails are interesting because their planning often is in the scope of recreation, but they also offer another option for daily commutes. In my case, I commuted from D.C. via bike for an internship one summer. The route involved the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, a relic converted into a 180-mile, hiker-biker trail. Though old, the isolated trail enabled me to take a break from city life as I was greeted by breathtaking landscapes along the Potomac River and occasionally accompanied by great blue herons soaring next to me. Like the public transportation infrastructure mentioned above, the trails involve planning that often goes overlooked. For instance, many of the trails in the D.C. region are known as “Rails-to-Trails,” referring to the conversion of old rail lines into bike paths. Bike trails can also be created in the form of closing roads, much to the dismay of drivers. But closed roads also provide benefits for citizens to enjoy the outdoors during the weekend without the need to build additional trails. I never expected recreational transportation infrastructure could be so complex.

Fundamentally, infrastructure is the art of designing systems that move people. It involves adapting to human traffic (due to work or otherwise) as well as adjusting prices to maximize revenue streams to fund new transportation projects. My encounter with the numerous transportation systems around our nation’s capital has enabled me to appreciate the factors and considerations involved in planning modes. Today, a bike, bus or rail ride is no longer just a means to get home but also an experience to appreciate how these systems are designed to move people efficiently.

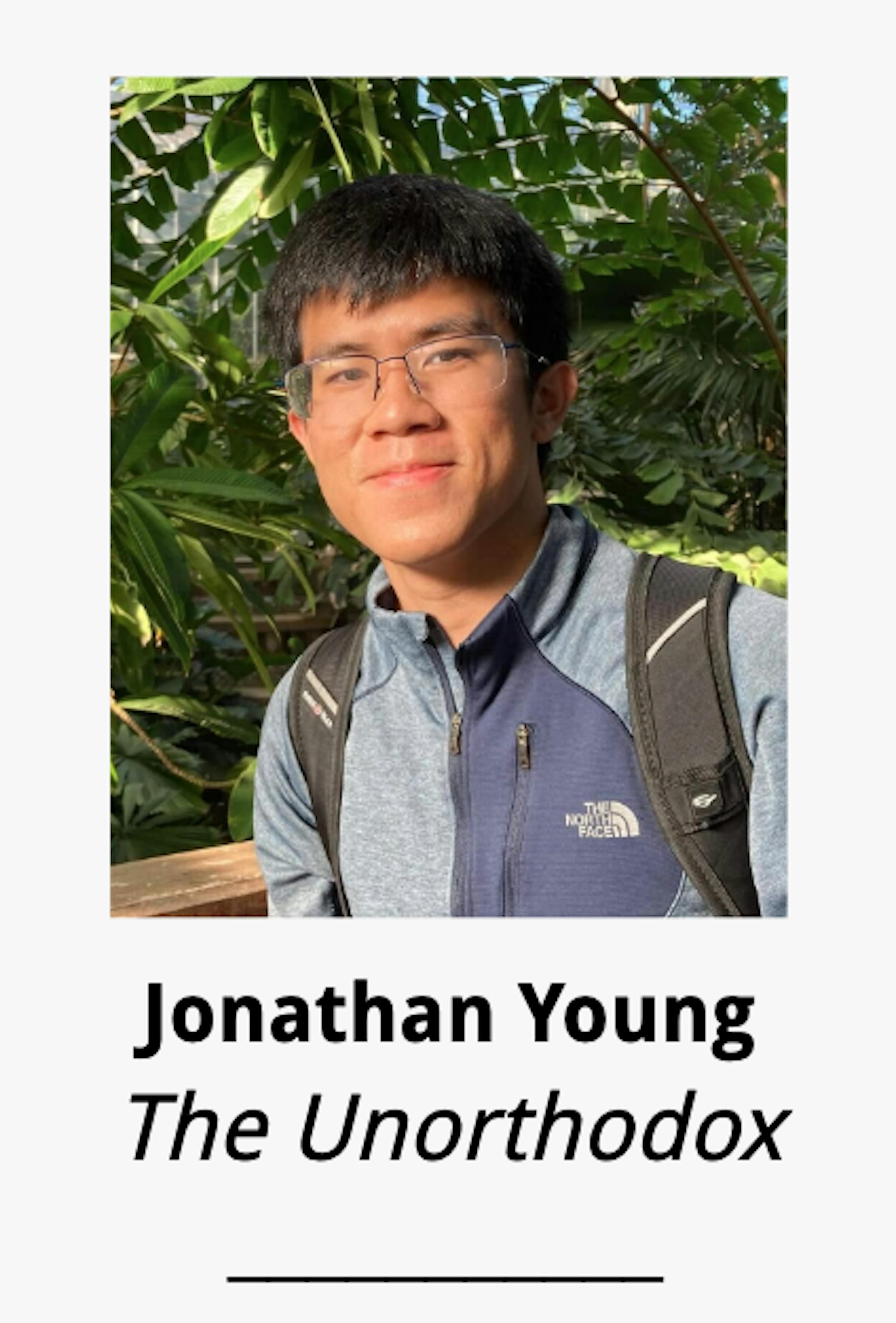

Jonathan Young is a junior from Potomac, Md., studying Computer Engineering. His column is about the nontraditional activities or events that have shaped him into the person he is today.