Defining art

As the boundaries of art continue to blur, the question of what marks art ‘good’ or ‘bad’ has become increasingly complex. These distinctions matter not just for critics or artists, but for anyone seeking to understand how creative expression shapes human thought and culture. However, before we can evaluate the quality of art, we must first ask a more fundamental question: What is art in the first place?

In order to define the idea of what is considered to be ‘good’ art versus ‘bad’ art, we must first define ‘art.’ In itself, art is the product of creation, mental and physical.

According to Immanuel Kant in Critique of the Power Judgment, art is defined as “a kind of representation that is purposive in itself and, though without an end, nevertheless promotes the cultivation of the mental powers for sociable communication.” If we characterize art as a tool of representation, we can argue that its value lies not in what it is, but in what it does.

Additionally, Leo Tolstoy defines art in What is Art in the thesis: “To evoke in oneself a feeling one has once experienced, and having evoked it in oneself, [...] so to transmit that feeling that others may experience the same feeling — this is the activity of art.” In Tolstoy’s perspective, art functions as a communicative bridge in which emotion is transferred from one consciousness to another. Therefore, the success of art depends on whether that emotional or intellectual experience is effectively shared.

Further, Albert Camus in The Myth of Sisyphus (specifically his chapter on “Absurd Creation”) defines art’s purpose as only to describe human experience, and not explain, and that an artist may only create a world that mimics our own: Art is a product of the absurd, defined as the conflict between humanity’s innate search for meaning or purpose and the universe’s indifference to such. As such, I argue that art is defined as a tool for communication, which then establishes that what qualifies as ‘good” art is its efficacy in transmission.

Novice art

Having established that art’s value lies in its capacity to communicate intention, we can now examine how this framework applies to varying degrees of artistic ability. ‘Novice’ art can be defined as art that is created with limited technical skill or experience (coming from an artist who lacks experience). The reason why the majority of ‘novice’ art is considered to be ‘bad’ art is that the usual purpose of novice art is to be aesthetically pleasing.

Take, for example, an image of a girl by a body of water, but the anatomy of the girl is incorrect, and the body of water does not obey the rules of physics. In itself, this piece would lean closer to the idea of ‘bad’ art, as the novice artist clearly demonstrates an engagement with nature and craft. By this, we mean that the artist shows an awareness of form and environmental context by their attempt to replicate a recognizable human figure within a natural setting. The failure, however, lies not in the artist’s attempt itself but in the piece’s inability to communicate a coherent message to the viewer.

Because the visual elements contradict reality without a discernible purpose, the work does not convey a feeling, idea or narrative that can be received by an audience. In this sense, the piece exemplifies an ‘absurd’ form of creation: It exists and is technically informed, but its intention to communicate is lost amid inaccuracy.

Child art

While novice art often fails through overreliance on form and technical ambition, the child artist represents the opposite extreme: art created with pure intention. A child’s art intends to communicate an experience or feeling. In this case, a child’s art may be considered ‘good’ art based on its intention, as it succeeds in expressing emotion without needing to use mediation or artifice. The child may not aim to replicate reality with utmost precision but rather aims to render the world as they perceive it. Through this lens, what distinguishes a child’s ‘good’ art from ‘bad’ novice art is not the level of skill, but its honesty in communication.

However, child art may still be considered as objectively ‘bad’ by a subtle distinction. While child art communicates effectively at an emotional level, it may lack the refinement, universality and complexity that allows a broader audience to fully grasp its message. While the child’s sincerity grants the work authenticity, the success of communication still comes from their inherent intention of conveying the message.

If the child’s creation lacks a discernible message, then it fails to fulfill the function of art as a vessel for meaning. In such cases, the piece may remain as a product of expression but not of communication. This highlights an important limitation: Effective communication is not only about intention but also how it interfaces with an audience.

Contemporary art

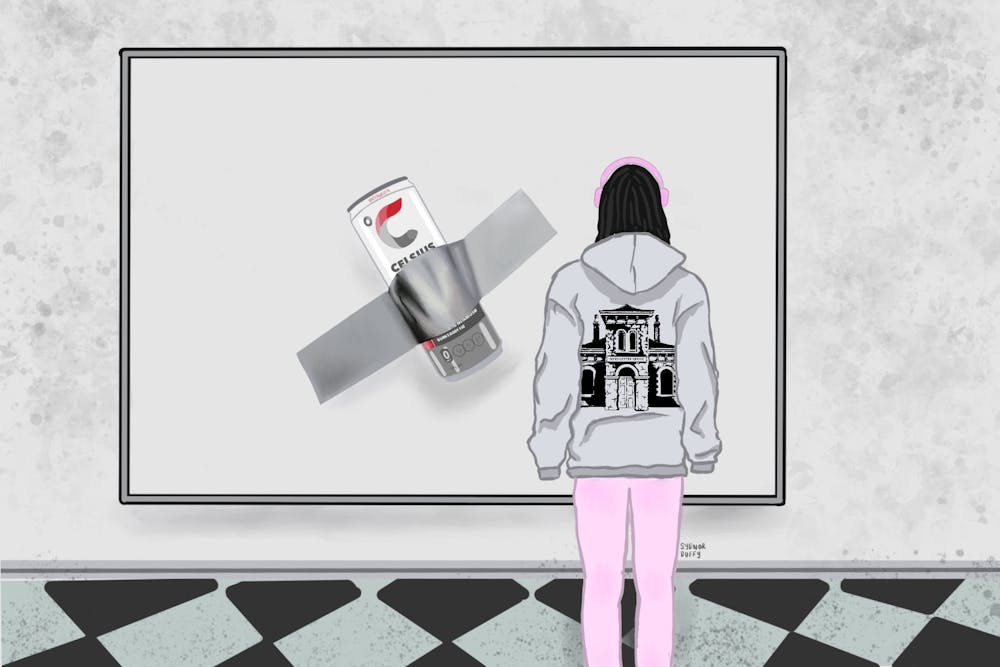

As we have examined how both intention and communication operate in novice and child art, we can extend this framework to modern and conceptual forms, where intention itself becomes the subject of the work. Take, for example, the contemporary art piece “Comedian” by Maurizio Cattelan. As a simple banana taped to the wall, many have criticized the piece as uninspired and an overall ‘bad’ piece of art.

Nevertheless, I argue that if we apply the established concept of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ art, the piece may fall into either category. If the piece intends to convey a sense of absurdism (as a reflection of the meaningless repetition of both life and the art world), I would argue that the piece is ‘good’ art, as it succeeds. This is because the medium itself reinforces the message. By taping a banana to the wall, Cattelan reduces the artwork to a familiar object that forces viewers to confront the arbitrariness of artistic value and the absurdity inherent in the art market. The humor and surprise generated by the piece communicate its intended reflection on absurdity. However, if the piece’s intention were to evoke sadness or intimacy, it would fail in that communication and be ‘bad,’ as its chosen form is incapable of conveying those specific sentiments. The success of the piece depends entirely on the alignment between intention and reception.

Yet, the events surrounding “Comedian” complicate this distinction. When performance artist David Datuna removed the banana and ate it, he transformed the piece into a new act of absurdism. By consuming the piece, Datuna revealed the instability of meaning in contemporary art. The controversy that followed thus became part of the piece itself. In this way, “Comedian” succeeds both through its subject and the discourse it generates. If art’s purpose is communication, then its intention and ability to provoke thought secures its place as ‘good’ art.

Art with no purpose

The argument that art with no purpose cannot be critiqued as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ art is ineffective. If there is art created that has ‘no purpose,‘ then the purpose of the created art is to have ‘no purpose.’ The critic must then ask: How effective is the art in conveying a sense of no purpose? Therefore, even art with the intention of having no purpose can be criticized by our categories.

Let us consider the idea of nature as art. Nature cannot be art per our definition, as it lacks origins of conscious intention. While nature may invoke beauty or meaning, these qualities are derived from human interpretation rather than from any communicative purpose within nature itself. A sunset may inspire awe, but it is not created with the aim of conveying a message or emotion. Thus, while nature can resemble art and serve as its subject, it cannot itself be considered art. The distinction lies in purpose: Art is the product of deliberate expression, while nature simply is.

This argument can be extended further into the metaphysical. If one believes in the creation of nature by God, then there is an inherent form of intention in the creation of nature, which would make it art. Within this framework, nature becomes an expression of divine will, communicating not through human intention but through the deliberate act of creation itself. This reinforces that art is defined by its capacity to convey intention.

The argument of subjectivity

The idea that good art is subjective must be separated from the concept of objective art. Judging ‘good’ art based on individual perception assumes that art’s communicative success is relative to the observer’s capacity to interpret it. However, if we define ‘good’ art as that which effectively communicates its intended message or emotion, then there exists an objective criterion by which to evaluate it: the coherence between the artist’s intention and the viewer’s reception.

The subjectivity of taste, such as a viewer’s preference for color, form and style, does not invalidate the objectivity of communicative efficacy. An artwork can be personally disliked and yet objectively successful in expressing its intended concept. This communicative success can be assessed by considering whether the intended message is accurately transmitted to the audience. Indicators might include critical reviews that identify the artist’s intended meaning or scholarly analysis that traces how the work’s elements convey specific ideas.

Conclusion

By defining art as a substance whose essence lies in communication, we create a framework through which ‘good’ and ‘bad’ art can be evaluated beyond aesthetic preference. Kant’s conception of art as purposive representation establishes that art exists for the sake of expression. Tolstoy extends this by grounding art in emotional transmission and Camus’ notion of absurd creation furthers this understanding, situating art as a mirror of experience.

Together, these views reveal that the defining feature of art is not its beauty or realism, but its capacity to effectively communicate intention. The question of what makes art ‘good’ or ‘bad’ is not one that concerns personal taste, but of coherent communication.

Kaylee Nguyen is a sophomore from Pensacola, Fla. majoring in Medicine, Science and the Humanities and Writing Seminars. She is a News & Features Editor for The News-Letter.