Working with cells requires knowledge, dexterity, time management and an absurd amount of confidence.

For years, I watched researchers culture cells in biosafety cabinets. I took notes as they changed out cell media (the liquid “food” cultured cells float in), passaged cells from one flask to another and conducted experiments on the microscopic organisms. When I began lab work in high school, my mentor allowed me to watch him culture the cells we used. I wanted so much to be the one on the bench, but I knew I’d have to wait until I had the experience, skillset and age required to handle cells.

As I became involved with my lab at Hopkins, I once again started taking notes on cell culture. My primary mentor explained each step he took and, after a couple of months, offered to let me try it.

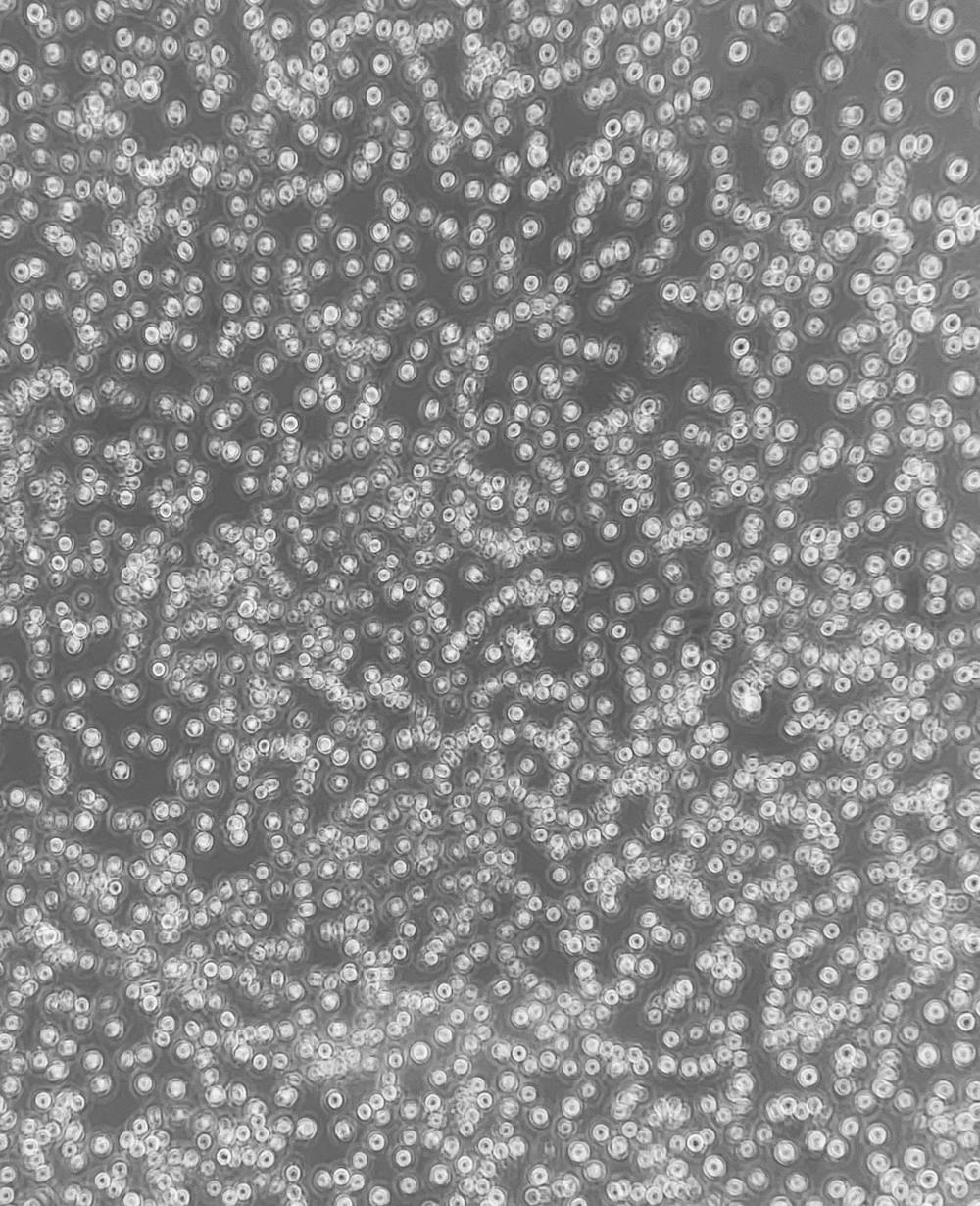

The first step in this process was to understand the underlying science behind cell culture. According to the National Institute of Health, cell culture is the process of growing cells in a controlled artificial environment, especially in the context of research.

I spent an afternoon with another senior laboratory member who gave me a cell culture crash course. I learned what the different types of cells used are, why it is important to passage them, how their shapes change with the artificial environments and what the basic equipment used at this lab is. He offered me a spare flask to practice with and, over the course of a few evenings, I rehearsed opening it single-handedly like he had shown me to.

Upon returning to my primary mentor, I studied his example. I wrote down each phase of the protocol and watched his movement — the way he sat (avoiding touching his arms to the hood), how often he sanitized his gloves with ethanol and the special grip he used to hold tubes and their caps together. And then it was my turn to try.

The knowledge I had gleaned went out the window. I was sitting in front of a sterile environment, expected to actually do stuff in a process where one mistake could render the entire cell line useless. The pressure was on.

My mentor sat next to me and motioned for me to start the protocol. I began with something I knew how to do: Opening the lid to the flask with cells. I twisted the cap off and put it down on the bench — wrong! My mentor quickly pointed out that putting the cap down led to an increased risk of microbial contamination. I picked the cap back up and tried holding it, contorting my hands to fit both the flask and the cap like I’d seen him do. The plastic dug into my fingers, but at least it was — wrong! Holding the cap opening down could disrupt airflow in the hood.

I corrected the mistake and kept going, needing my mentor to prompt me before each step. There were dozens of factors to keep track of and so many steps to remember that I spent most of the process a little overwhelmed. But it was exhilarating. This was the same process I had watched so many role models go through, and I was finally taking it on myself. I also enjoyed the individual steps – transferring solutions between containers and applying the theory I had learned, which was honestly quite awesome. At the end of the process, my mentor asked what I thought of it. I answered as truthfully as I could: “Fun.”

The next time I tried cell culture, it went only slightly better. I was able to avoid putting the cells at risk of contamination, but the steps were still confusing; I was having a hard time remembering when to do what. When my mentor noticed, he offered me some of my favorite laboratory advice so far: “If you forget the steps, remember why we do the processes.” Focusing on the logic behind each step, instead of the step itself, made the protocol far easier – it was finally making sense. Within a couple of weeks of practice, I became faster and more efficient with the process.

I eventually gained the confidence to do it unsupervised. Without a mentor to call me out on mistakes, I continuously check myself throughout the process. Does the thing I just did put anything at risk of contamination? Am I holding this correctly? What is the next step in the process? How should I manage time so the process flows smoothly? My mentor recently asked if I still find cell culture fun – how could I not?

My learning of cell culture would not have been possible without the people who shaped my time in research. From the mentors at Florida International University who first introduced me to the concept to the mentor at Hopkins who has spent hours at the biosafety cabinet with me, I am grateful for the people who made my learning possible, and I hope to become one of those mentors for someone else someday. Though there is still a lot left for me to learn (the other day, I spent two hours trying — and ultimately failing at — a new protocol), I am eager to continue with this amazing part of my lab routine.

Like many good things, however, cell culture comes with its problems. There are various ethical considerations to keep in mind, and don’t get me started on the amount of biohazard plastic waste that laboratories produce. But cell culture is helping us shape a better future in science, health care and other related fields. It’s an amazing feat of technology and one I am excited to finally be a part of.

Sara Kaufman is a freshman from Fort Lauderdale, Fla. majoring in Biomedical Engineering. Her column focuses on the experiences she’s had and lessons she’s learned outside the classroom.