Prescription to Prediction: The Ancient Sciences in Cross-Cultural Perspective conference brought Egyptologists, Classicists, ancient Near Eastern scholars and science historians from around the world to Scott-Bates Commons on Oct. 6–7 to discuss intercultural exchange of medical and scientific knowledge in the ancient world.

The conference, produced by the Scientific Papyri from Ancient Egypt in Cross-Cultural Perspective (SciPap) project, is the third of its kind — the previous two took place in Copenhagen in 2018 and in New York in 2019 — and was sponsored by New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW), the National Endowment for the Humanities Collaborative Convening grant and Hopkins’ Singleton Center for the Study of Premodern Europe and Department of Near Eastern Studies.

ISAW Doctoral Candidate and SciPap Collaborator Amber Jacob discussed SciPap’s overarching goals in an interview with The News-Letter.

“The whole purpose of the conference series is to bring not just Egyptologists working on science together, but scholars from adjacent disciplines... because this is a very interconnected world where there's so much interaction in the sciences,“ she said. “We don't want to just be studying these texts in a disciplinary bubble, we want to really expand that conversation so that as new texts are being published, they're having scholars from other disciplines, informing the way that we're reading and interpreting these texts.”

SciPap, founded at the University of Copenhagen in 2017, was created to study, translate and publish the Papyrus Carlsberg Collection, the largest collection of Demotic medical and astrological texts. Demotic is a form of the Egyptian language utilized between 650 BCE and the fifth century CE that historically has received less attention from scholars than its earlier counterparts.

One goal of the collaboration is to shed light on Egyptian contributions to Western medical traditions, which are often said to begin with the Greeks. This myth persists despite a 2000-year history of Egyptian and Near Eastern medical practice prior to writers like Hippocrates. These sources, however, are portrayed as irrational and magical. One reason for the lasting legacy of this myth is the lack of Egyptian source material from the periods when trans-Mediterranean contact was greatest — to which many of the Carlsberg Collection date.

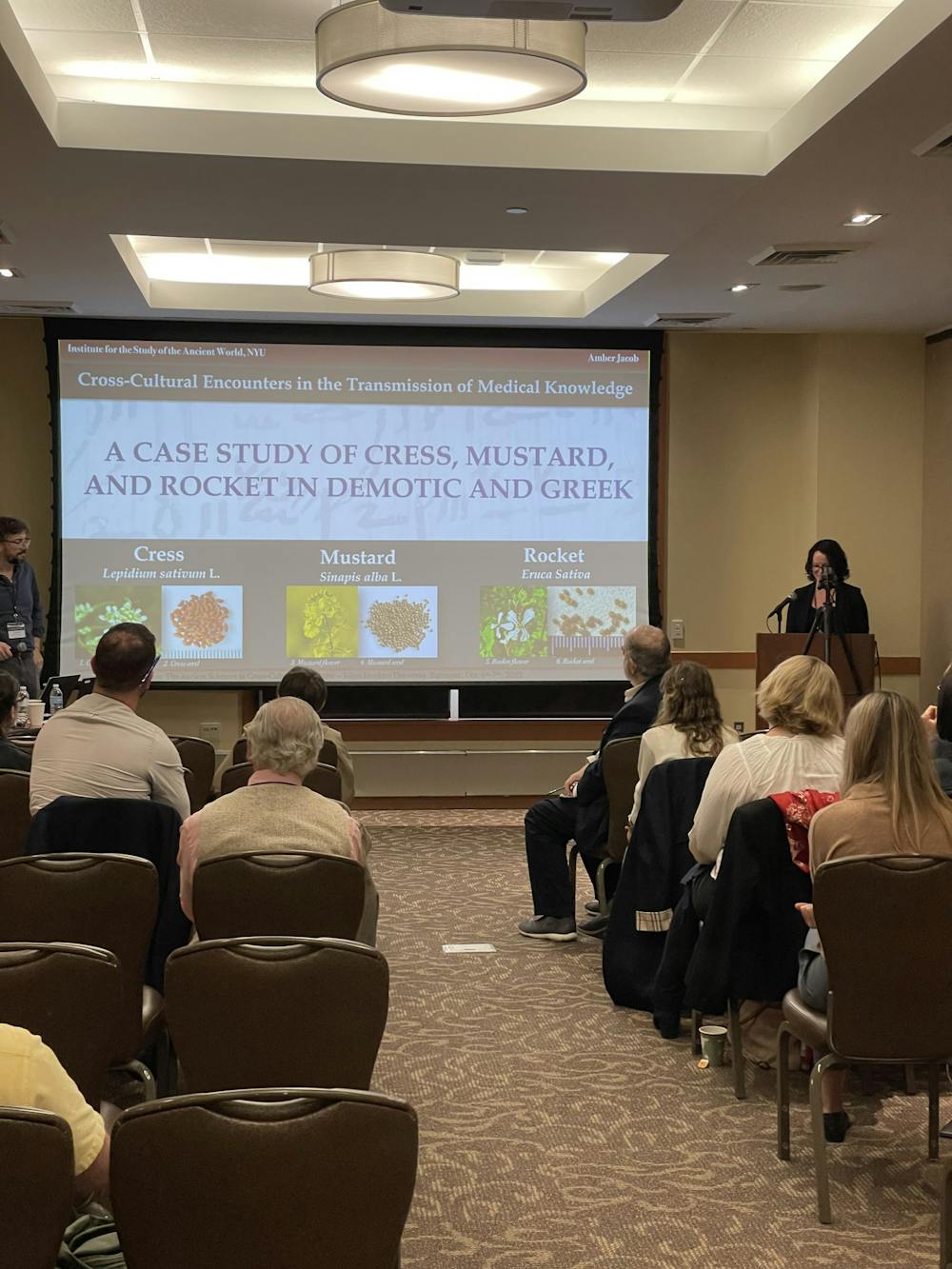

This lack of Egyptian source material results in a one-sided view of the origins of Western medicine that ignores non-classical additions. Her presentation “Cross-Cultural Encounters in the Transmission of Medical Knowledge: Case Studies from Graeco-Roman Egypt,” gave an example of one such transmission of a cress, mustard and rocket-based prescription to treat lichens, wrinkles and leprosy found in Egyptian, Greek and Roman sources.

Far from originating in Greece, the treatment passed to them through Egyptian hands with linguistic analysis suggesting an even earlier origin in Persian sources. This process of communication gives a clear example of the complexity and multidirectional of ancient pharmacological and medical knowledge.

In an interview with The News-Letter, Hopkins Professor of Egyptology and Chair of the Department of Near Eastern Studies Richard Jasnow shared his experience visiting the collection.

“I went to [see the Carlsberg Collection in Copenhagen] with a German scholar in the 70s, one of the great masters of our field,“ he said. “We looked at that material, and as he was going through the files, he just said to himself, ‘There is material here for 100 generations.’ It’s very exciting and humbling for us to be able to be part of this process of recovery.”

While this material possesses more historical than scientific significance, Jasnow firmly believes that studying ancient sciences can further our own understanding of both modern science and of the human condition.

“Engaging with these sorts of issues, cures us a bit of our hubris... because it exposes people to virtually new worlds, and much of what these people thought really resonates with us now,” he said. “It's just a good thing and an inherently positive thing that we should be aware of what these people thought and that sort of helps us get out of our bubble.”

Jacob agrees with Jasnow’s analysis adding that these texts speak to problems that no longer exist in the modern world, such as the violent, manic throes of fever, and highlight a legacy to which modern science is indebted.

“Anytime you're studying a modern discipline, it helps to understand the history of that discipline because it does pull you out of the world you've been raised in and gives you a little bit of a broader perspective,” she said.

Over the course of two days, the conference covered 25 papers on topics ranging from Babylonian astronomy to dream divination and from Islamic alchemy to Greco-Roman theories of digestion. The conference was hosted in a hybrid format, enabling participants to attend from around the world.

Jacob described how, in addition to the lecture component, the conference enabled SciPap collaborators, to discuss their work with their peers and grow as scholars.

“The project has a component where it trains [doctoral] students to do this type of work,“ she said. “We present our work at the conference; we have these specialists in Demotic already convened, so then we host a workshop so that those of us who are reading these unpublished texts can say, ‘I can't read’ this and we get to have the benefit of having experts look at it.”

Jasnow mentioned the beauty of this collaboration, noting that it has been enhanced by technologies like Zoom which facilitate further conversation.

“We all have trouble reading this script, and it's really a beautiful thing to have people get together and someone says, ‘I got this, this group here, this sign and I just don't know [what it means]? What do you think? I’ve looked at it for two years,’ and then through the wonders of Zoom, professors in Germany, England and many different places can participate,” he said.

As the long process of translation and interpretation continues, Jacob encouraged members of all STEM fields to investigate their field’s ancient roots and understand the struggles that brought science to modernity.

“This is an academic tradition that has a very long history,“ she said. “If you only just jump in, and all you have access to is this one little slice and particularly if that slice happens to be very specialized, you’re missing a lot.”