On Jan. 19, the Equal Access in Science & Medicine seminar committee at the Hopkins Disability Health Research Center hosted Dr. Chad Ruffin as a speaker for their monthly lecture series.

Ruffin gave a lecture titled “A Deaf Surgeon Comes Into His Own: Insights for Improving Outcomes with Hearing Loss,” where he not only talked about the challenges he faced in his time in the medical field but also discussed internalized ableism.

Ruffin is an otolaryngologist — an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist — and has worked as an auditory scientist and a tech innovator, developing cochlear implants to aid those with hearing disabilities. He completed his surgeon residency and research in cochlear implants at Indiana University School of Medicine.

While recounting how being deaf had affected his professional life, Ruffin pointed to his experience of applying to residency. He explained how he was typically treated with skepticism in interviews instead of interest in his work in cochlear implant devices and his experience speaking to heads of state about hearing loss and disabilities.

“I sat on the sideline and watched my colleagues get into the top programs with similar credentials and I felt like I had been denied a seat at the table that my implant was supposed to give me,” Ruffin explained. “Despite my parents telling me that with hard work, nothing was out of reach... no one wanted to take a chance on me.”

Hearing loss affects around 15% of all Americans and, according to Ruffin, 5% of children with mild hearing loss even in one ear are at higher risk of failing a grade. On average, those who have hearing loss have about half the employment rate compared to those with normal hearing.

While the medical field has developed new technologies to aid those with hearing loss, Ruffin still believes that more must be done both in science and society to have a true impact on the community.

One idea that Ruffin emphasized in his lecture was that hearing loss is more than a sensory deficit. While we can aid those with hearing loss with cochlear implants, these devices, while extremely useful, are not able to fully give one the full experience of those with normal hearing.

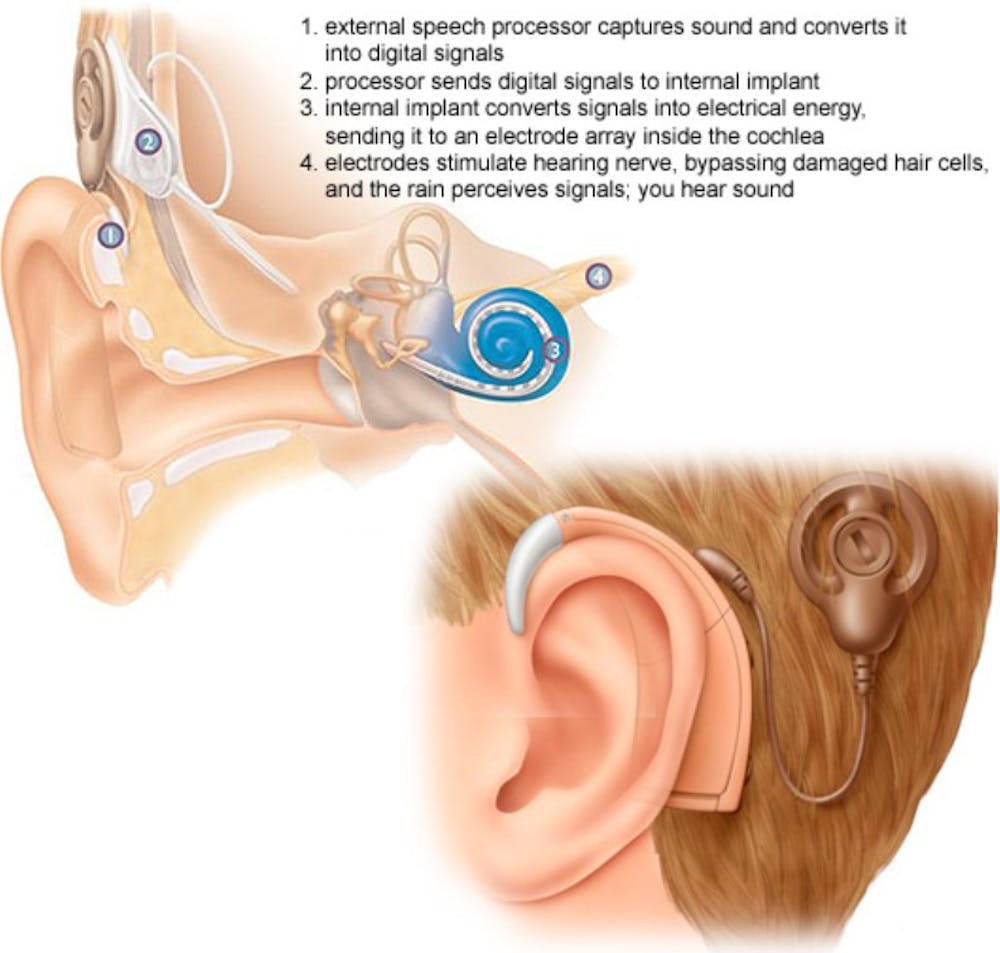

Cochlear implants are electronic devices that can partially restore one’s hearing capabilities. They are neurostimulators that are implanted into the inner ear to bypass any damage on the cochlea. The implant converts sound into electrical signals to stimulate the auditory nerve. This, in turn, gives the user the sensation of hearing sounds.

However, as Ruffin demonstrated in his lecture by playing a recording of what one hears with the cochlear implant, the quality of sound the user hears is still relatively muffled and imprecise.

Ruffin described how those with hearing loss may suffer from a increased cognitive load; so much cognitive energy is spent in conversations on deciphering the words, that people are prevented from being able to think ahead in conversation, which can be a huge disadvantage in professional settings.

In addition, those with hearing loss may have a harder time in social settings as an inability to decipher different tones and inflections may prevent someone from reading social cues. Implants help to make sound louder, but don’t necessarily help with the lack of clarity.

Furthermore, having deficit hearing as a child may also help to prevent some children from gaining many softer social skills, since they are unable to hear surrounding conversations and activities that contribute to incidental learning as a child.

It took Ruffin about 30 interviews over two years before being admitted to an otolaryngology residency program after medical school to get training in the surgical specialty that deals with communication.

“You can’t go through that much opposition and lack of invitation without wondering, many times, if you really belong in a field,” Ruffin said.

He continues to talk about his personal experience with internalized ableism that comes with disability and how he was able to build confidence over the years.

While many structures and offices are now in place to aid those with hearing loss and other disabilities, Ruffin talked about how, while these accommodations are necessary and helpful, the vulnerability that comes with taking these accommodations can be difficult and can even feel shameful.

“I’m very, very proud of what I do now, but it was not without talking to other people, getting perspective, finding mentors to really overcome this internalized ableism or shame,” he said.

Ruffin learned to cast a wide network, talking to different professionals to learn and better himself as a surgeon, scientist and communicator. He grew to realize that his lived experience as someone with hearing loss is, as he said, a “fellowship and advanced training within itself.” He takes pride in his story and realizes that his experience helps him to connect and communicate with patients with similar experiences.

Correction: This article originally stated that those with hearing loss experience a decreased cognitive load. They experience an increased cognitive load. The News-Letter regrets this error.