Hopkins Medicine has long been known as a pioneer in its field. One of its remarkable aspects is its efforts to involve women in the medical field since its establishment.

“I desire you to establish, in connection with the hospital, a training school for female nurses.” A notable proportion of Johns Hopkins’ will, which was published closely after his death, was dedicated to founding a School of Nursing.

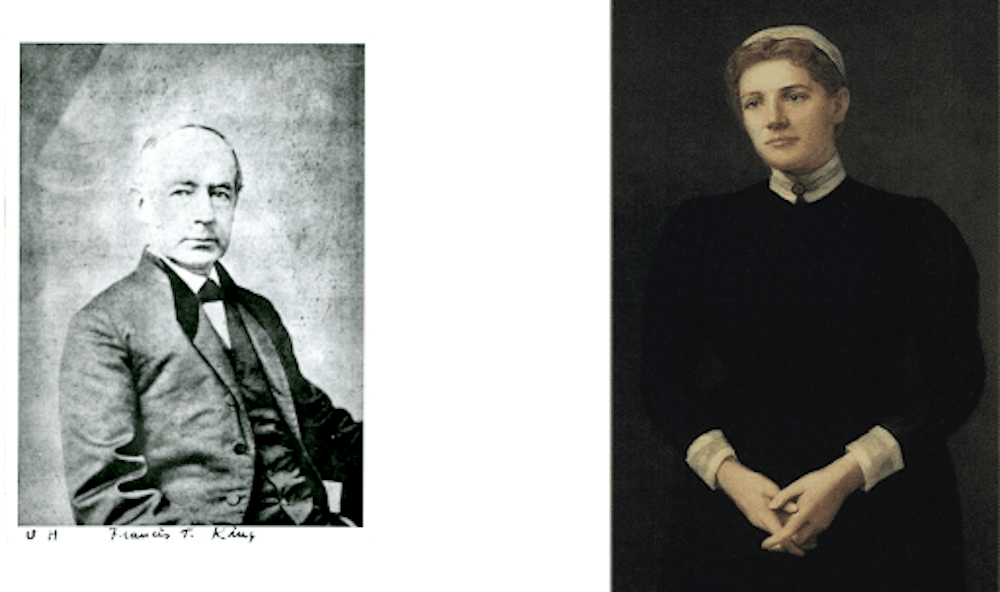

In 1876, as the Hopkins Hospital was nearly prepared to open, the establishment of the School of Nursing was also underway. Francis T. King, a member of the Board of Trustees at the time, travelled to England to consult Florence Nightingale on what the University should model this School of Nursing after. Burdened by domestic affairs, Nightingale could not visit the U.S. herself, so she exchanged letters with King and sent a copy of her Notes on Hospitals.

In the following years, King would continue to recruit faculty and staff for the school and the hospital. In 1889, shortly after the completion of the Hopkins Hospital, the School of Nursing welcomed its first class, with Isabel Hampton serving as the principal and superintendent nurse.

To gain admission, candidates had to pass an exam in reading, writing and math. They were also notified that after fulfilling the training and passing the exams for graduation, they were expected to serve the hospital for at least five years. However, those demanding criteria did not intimidate candidates — the first class had a size of around 20.

Those young women were admitted intermittently, and due to shortage in staffing, many of them were immediately placed on duty.

“It reminded me of the initiation of students in fraternity house,” said Georgia Nevins, a member of the first class, as documented in a catalogue of the School of Nursing.

Hampton recognized that the top priority was to formalize the training of their students, and soon turned better in the following year. Documents show that in 1890, the school operated under an organized structure of six head nurses, four staff nurses and 17 nurses-in-training. The students were also promised a combination of lectures as well as field experience. In fact, many of the lectures the first class received were given by three of the four doctors appointed as the first deans of the hospital.

The field experience proved helpful for the preparedness of the students in training. A year after its establishment, the School of Nursing had already started to gain international fame, welcoming visitors from nationwide and overseas.

Women also played key roles during the founding of the School of Medicine. In 1876, the Hopkins Hospital first opened its doors to patients. Twelve years later, just as the construction of hospital facilities was reaching completion, the University found itself in an awkward position of not having a large enough budget for the originally-promised School of Medicine.

Faculty at the hospital were anxious to see the pre-med undergraduates they had taught at Hopkins turning to offers from medical schools elsewhere. They appealed to the Board of Trustees for a pressing need to raise funding for the School of Medicine. In the meantime, the Women’s Fund Committee, a group of women passionate about obtaining opportunities for medical education for women in the U.S., extended an offer to donate to the School of Medicine.

At the center of this committee were five well-educated, wealthy and unmarried women who were all daughters of trustees of Hopkins.

The one leading this movement was M. Carey Thomas. An English professor, Thomas was well aware of the value of harnessing the media to spread their influence. Following the launch of the committee in May of 1890, she rapidly enlisted participants, and the organization soon grew to have regional representations across the nation, with prominent members such as First Lady Caroline Harrison. That fall, Thomas, on behalf of the Women’s Fund, officially proposed a donation to the University, offering a sum of $100,000 on the terms that the school would hold the same criteria of admission for women as they did for men.

While Thomas initiated it, this campaign would not reach success without the efforts of Mary Garrett. Although her terms were appealing, the University was still hesitant to extend medical education to women. Many believed that women were not competent enough for academic work, and too frivolous for tasks in the medical field. Daniel Coit Gilman, the University president at the time, had privately written to the Trustees, suggesting alternative plans to raise funding.

Eventually, the Women’s Fund settled on an agreement with the Trustees that they would contribute a total of $500,000. Yet the committee was still more than $300,000 short of this amount.

This was when Garrett came into the picture. Previously, she had inherited the Baltimore and Ohio Railroads from her father, becoming the wealthiest women in the country. Due to her family business, she had a unique grasp on professionalism and entrepreneurship. Garrett offered to fill the $300,000 gap herself, while adding another condition: All male and female candidates, in addition to having a Bachelor of Arts degree, must also pass an entrance exam that tested French, German, physics, chemistry and biology.

Garrett exchanged numerous letters with the University and the medical faculty to have her terms accepted. In 1893, she took to court an extended statement concerning the terms of how her gift should be accepted, with which the University eventually agreed.

At the end of that year, administration and faculty came together to draft the announcement of the establishment of the Medical School, which recognized Garrett’s contributions. Starting from its very first class of graduates, the Medical School had women.

Although the terms were accepted, many were still apprehensive about the decision to accept women. However, time proved Garrett’s vision correct. Dr. William Welch, the first Dean of Physiology, who was formerly among the voices of opposition, later admitted that Garrett’s demand to raise the standards of acceptance altogether did allow the school to produce more competitive graduates.

“Where man has hesitated and has been impelled by women to take the first steps.” This was how Dr. Alan M. Chesney, a former dean of faculty at the School of Medicine, wrote about the efforts of the Women’s Fund in The Johns Hopkins Hospital and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine: A Chronicle.