The Writing Seminars Department invited the acclaimed poet Richard Kenney to share his philosophy on writing poetry and read some poems from Terminator, his new and fifth published book of poetry and his first since 2008.

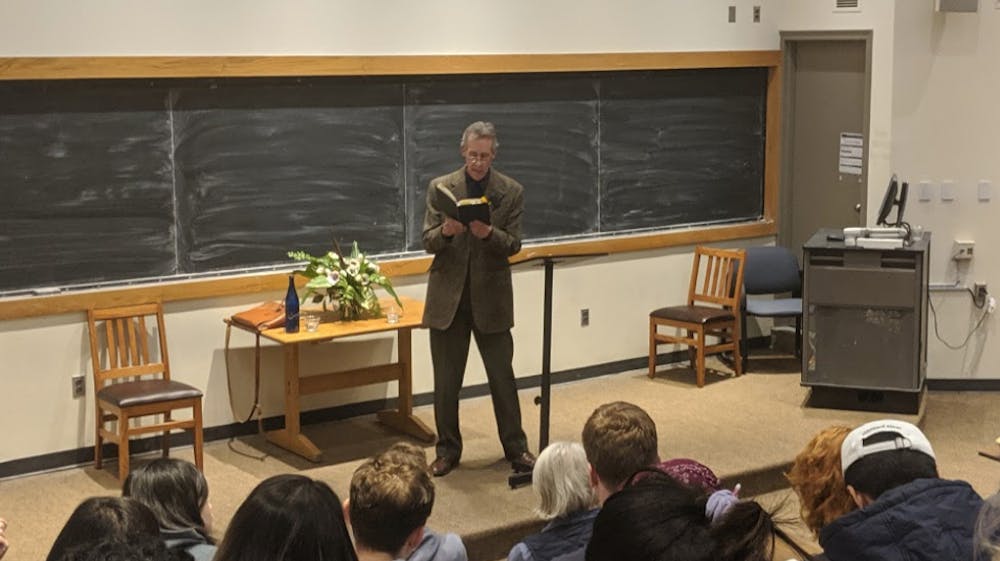

The reading took place on Nov. 6 in Mergenthaler 111, which was so full that many attendees had to sit on the floor.

Resident poet and professor Mary Jo Salter introduced Kenney. She then proceeded to ask him about his thoughts on the difficulty of poetic language, especially since he is known for writing complex and dense poems.

Kenney expressed his feeling that poetry must be written in a way that makes it “function best.” He also warned the audience that an attempt to make poetry more accessible can, in actuality, harm the integrity and quality of the poem.

Kenney also spoke about the integration of science into his poetry. Though he admitted that he is not an expert in science and mathematics, he expressed his fascination for the world around us. Even if he can only understand it to a certain degree, he said that he seeks to learn as much science as possible and that he allows that knowledge to influence his art.

Salter then asked Kenney about his use of meter and rhythm, allowing Kenney to delve into his love for words and language beyond the exploration of science.

For Kenney, meter and rhythm are extremely important echoes of our yearning for fulfilling aesthetic experiences. They are the answer to our desire to hear satisfying sounds. He admitted that it can be disheartening to work with these tools when other poets have already mastered them.

“How can I even try to write with rhythm knowing that I’ll never grasp it the way Tennyson did? Why even bother trying to use meter when we’ll never be Shakespeare?” he said.

As an answer to this question, Kenney explained that it is not about being perfect, as some poets have been and can be. Rather, poets should use these tools to create better poetry that can sound the way they want it to — even if it’ll never be as good as John Milton’s work.

The discussion also led into Kenney’s method of organizing his poetry collections. Kenney described his redacting process as “spelunking,” where he carefully curates his works from the past decade and separates them into distinct categories and chapters. Once finished with that more basic task, he goes about finding a theme for the book. In the case of Terminator, it was a shift from lighter, happier poems in the beginning to darker and heavier poetry in the second half.

It was this contrast that inspired the title of Kenney’s book. Terminator refers to the terminator, the line perpendicular to the equator that separates night from day.

Kenney said that he hated that title. Still, he admitted that he hated it less than all the other titles his publisher had suggested to him.

After discussing his work, Kenney went on to read a selection of his own poems.

The first of his poems that he read was a composition titled “Poetry.”

It was a short poem and made a simple claim: Nobody really reads much poetry, as there are other ways to have fun.

But, as Kenney wrote, “who would wish to live in a culture of which future anthropologists would say, / Oddly, they had none?”

“Poetry, I think, is the distant thunder-sound in the drying ink,” Kenney read.

Members of the audience seemed moved by his poetry.

In addition to reading “Poetry,” Kenney also recited one of his longer poems about a theoretical chimaera.

In Greek mythology, a chimaera is a monster with a lion’s head, a goat’s body and a serpent’s tail.

Kenney’s chimaera, though, was not a lion, a lizard or some other mythological combination. Rather, it was a sci-fi amalgamation of a human and a chimp.

Kenney raised many questions about how the world would receive such a creature. He came up with different imaginary headlines from newspapers and websites that would fearfully herald the birth of the chimaera. In Kenney’s poem, the surrogate mother of the chimaera was horrified by what she had helped to create.

These difficult and disturbing questions all remain unanswered, though. In the end, the chimaera only lived for five weeks.

Kenney also read a poem called “Schrödinger’s Elephant,” in which he certainly demonstrated his command of scientific language.

He began with reading about “blind men” who “met to scratch the quantum noggin.”

Kenney continued to use very difficult scientific terminology, discussing “the wave function of the pachyderm.”

The final lines of the poem, while dense, were perhaps some of the most powerful that Kenney read all night.

“Human? — How in heaven’s name — / The answer’s mathematical as all Creation, involving probability and Chance… Laypeople simply can’t—look, no offense, but try now not to think of elephants,” he read.

Overall, the reading was a really fascinating look into Kenney, a poet who challenges readers with his complex works. Moreover, the reading gave valuable insight into how poetry and science can intersect.