I’m 22 years old, and I still think that one of the most heartbreaking sounds is hearing your parents cry. Last week, I was on the phone with my dad, and he started to choke up. He was calling to tell me that Jamie, our family friend, has about two weeks left until her organs fail. She has been struggling with terminal cancer for a few months now.

Jamie is 46 years old and has two boys — an eight year old and a six year old. I’ve known her since I was around her kids’ age; it was at that time when her husband, Derek, started to work with my dad.

I always liked Jamie. She has a soft smile and a calming energy. When I was little, I wanted to have long, shiny black hair like her. I would tell her, over hot, steaming bowls of ramen, about my plans to go to a boarding school — Hogwarts was the dream, but any fancy British school would do. Once, Derek, Jamie, my dad and I went to a Giants baseball game, and Jamie took me around the park when I got bored. Whenever we went to her house, she would serve interesting snack combinations, like prosciutto and tea.

Those were the things I thought of when my dad told me about Jamie. I wondered if memories are really all that make up a person. And then I just felt empty. There’s a universal sadness in knowing that children will grow up without one of their parents. It makes you question everything. In other words, it can bring about a full-on existential crisis. How is it okay, how is it fair, for children to lose their mother when they’re young? How can someone so young, and so kind, die?

If you’re a nihilist, you would probably tell me that everyone dies and life is meaningless, so what’s the point of being sad? And I’ll admit that nihilism is appealing, seductive even. It requires little of us except our passivity and a continual repression of emotions.

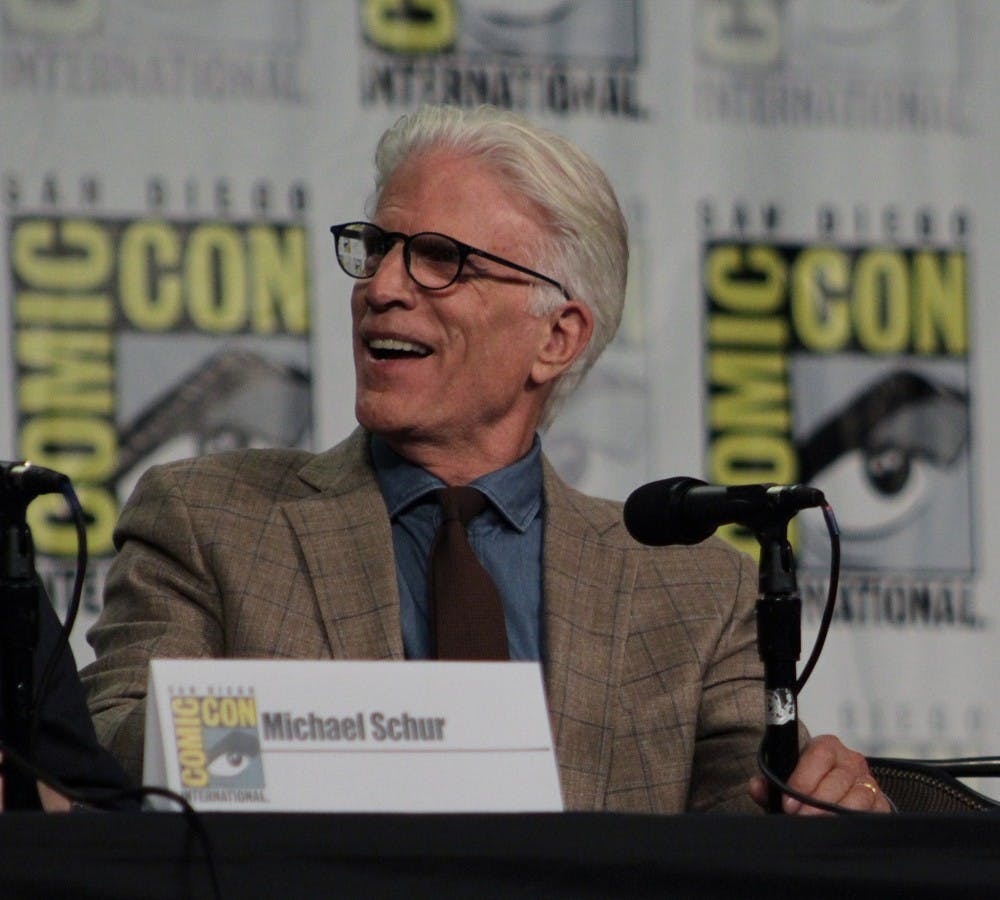

So I thought more about those questions, and I ended up revisiting a scene from the TV show The Good Place over and over. The basic premise of the show is that an awful person, Eleanor Shellstrop (Kristen Bell), accidentally ends up in heaven and decides that she wants to learn to become better in order to stay. In the fifth episode of the second season, “Existential Crisis,” the show tackles its essential question — can morality be taught? — with a twist.

Michael (Ted Danson), the architect of one of the neighborhoods in the afterlife, is an immortal being and thus doesn’t understand morality or ethics. His actions have no consequences because his life is infinite. But when he comes face to face with the concept of death, Michael is launched into his first existential crisis. And it doesn’t suit him.

Eleanor, determined to help Michael out, is forced to come to terms with how she repressed her feelings on Earth, and how it contributed to her living a selfish life.

“Do you know what’s really happening? You’re learning what it’s like to be human,” Eleanor says. “All humans are aware of death, so we’re all a little bit sad, all the time. That’s just the deal. And if you try to ignore your sadness, it just ends up leaking out of you anyway.”

The scene is a short one, but it really packs a punch. Is it true that the finiteness of our time injects meaning into existence, that grappling with mortality helps us live more meaningful lives? I’m not sure. But I do feel like confronting death can help us figure out our priorities.

It’s easy to get caught up in the monotony of everyday life and focus on the things that are stressful or awful or annoying. But those things also don’t seem that meaningful when you think about loss and impermanence. The truly important aspects of life come forward in the face of death. When I thought about Jamie, I remembered small moments, conversations, meals shared. Feeling cared for and feeling safe. I only remembered the little things. Those are truly what make life special and worthwhile, even if looking back on them make us feel a little bit sad.