Chances are that if you’re here, you’ve always had a passion for knowledge, whether it manifested itself in a love of books (as was the case for me), an intense interest in taking things apart and reassembling them, or in playing “doctor” and “operating” on your siblings.

I was the girl that woke up an extra hour early before I had to be at the bus stop to read Harry Potter. Upon arriving at school, I made my way through my classes in anticipation of the refuge that recess would bring, when I could once more retreat into the world of the novel in my hands rather than face my unforgiving peers.

To this day, if you’re one of my friends, you know that books are my favorite kind of gift to give and receive. While each one of us has our own unique experience when consuming a novel, there’s something beautiful about sharing a story with someone whom you think will enjoy being immersed in it.

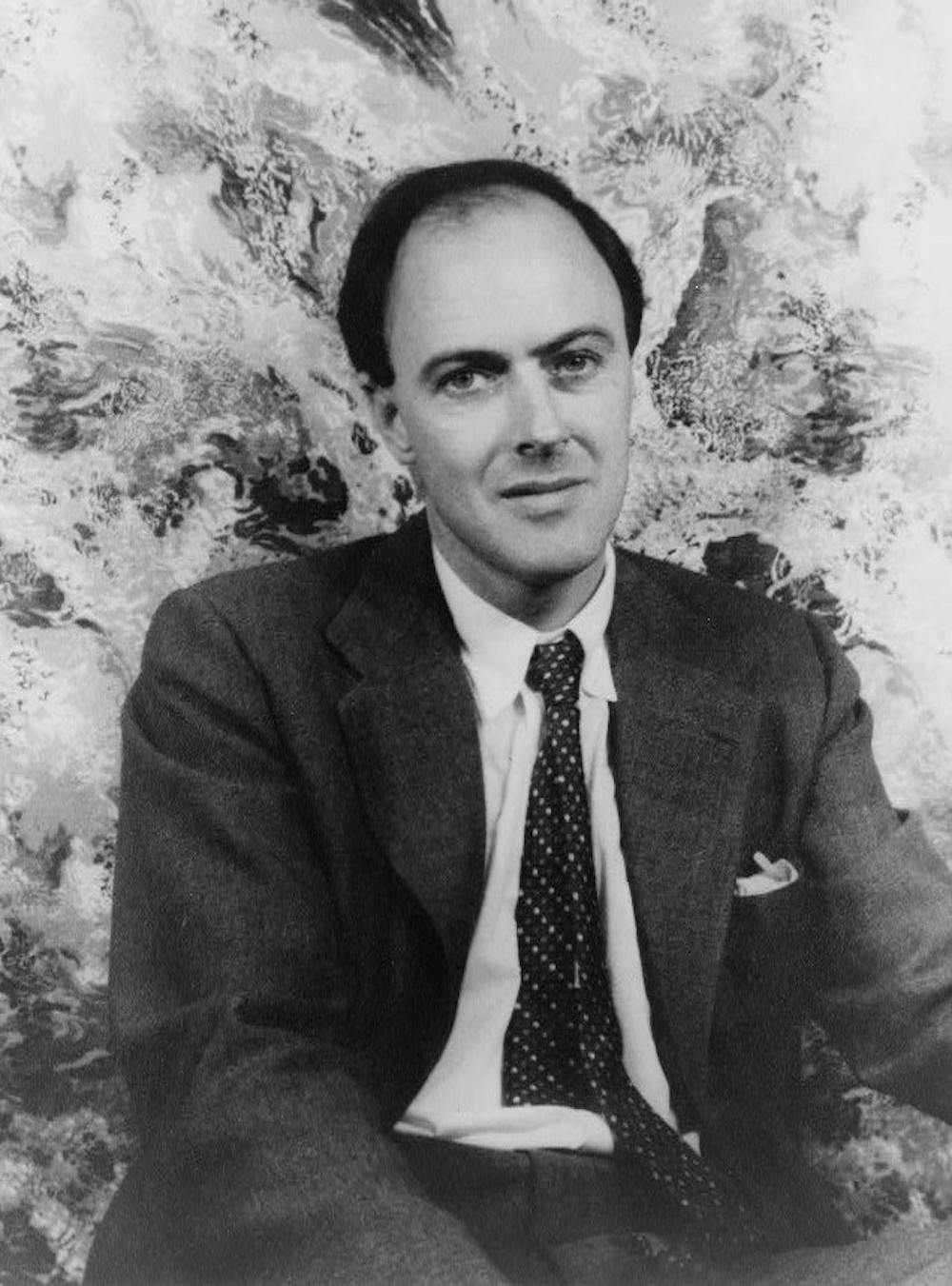

Of course, I owe much of my love for reading to my parents for taking the time to teach me how to do so at a young age. I was reminded of my gratitude for the efforts my parents made in fostering this interest in the early stages of my life when I saw that this week marked the 30th anniversary of Roald Dahl’s classic book, Matilda.

To mark the occasion, a pair of statues has been temporarily installed by The Roald Dahl Story Company in Great Missenden in Buckinghamshire, England. The statues feature a defiant Matilda facing off against none other than Donald Trump in lieu of her nemesis in the novel, Miss Trunchbull.

After what was a particularly frustrating and triggering week for many women, especially survivors of sexual assault, there was something that felt refreshing about this image of a young, bookish girl justly expressing her anger toward not only our current president but also the patriarchy as a whole.

As I reflected on how I gradually found my way from being a curious five-year-old girl that questioned the rules of the world around her to transforming into an adult looking to engage in activism through pragmatic actions both big and small, I felt buoyed by a sense of hope.

Should I have a daughter, I am optimistic that she (as well as the rest of her generation of informed girls) will act in the spirit of both the fictional heroine Matilda and real-life women who continue to take a stand such as Dr. Christine Blasey Ford and Kamala Harris.

As I watch Rebecca Traister and Soraya Chemaly publish works about the constructive rather than the destructive power of female anger, I am hopeful that scholarship in this realm will continue to find an audience of women looking for the validity of their emotions to be affirmed rather than denied.

Gradually, as a healthier conception of the role of emotion in women’s daily lives seeps into the public consciousness, I hope that we will no longer feel such intense societal constraints around what is considered acceptable for us to express.

Yet, I must acknowledge that, while the manner in which women have given voice to their stories as of late has highlighted a set of all too common shared experiences, the ability to acquire knowledge, as well as to be able to afford expressing one’s anger, requires a level of privilege that not all women possess.

In fact, when it comes to reading, which is arguably one of the primary means through which women can educate themselves, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), young women worldwide make up at least 59 percent of the illiterate youth population. The narratives that fill our heads as our eyes take in ink on a page, our imaginations captivated, have an immense power to shape our worldview.

The story of Matilda is just one example amongst hundreds — one in search of similar work containing strong, young female characters must look no further than to Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, which is celebrating its 150th anniversary.

If we want to continue to elevate women’s voices, not only in the U.S., but also around the world, we need to ensure that young women are given the opportunity to receive an education.

At the end of the day, we can theorize all we want about the power women’s words wield, but if young girls are not equipped with role models to look toward or the lexical toolbox to express themselves, then we cannot expect such dynamic conversations around gender norms and acceptable behavior to continue to thrive in the future.