One of the most daunting burdens faced by Hopkins students is the grueling task of reading an endless flow of papers, articles and documents. It is an arduous task that is ignored by some and reluctantly performed by others. But there is a way to easily harvest the valuable knowledge within these texts through the concept of active reading.

I learned about this concept in my Reintroduction to Writing class through four authors who are stringent advocates of active reading. The idea of active reading involves engaging in deeper interaction with the text, such as questioning the author or marking up the text. I believe active reading helps improve performance in writing-intensive courses and is a valuable skill for students of all disciplines. I’ve learned that it’s important to break free of unfounded respect for written text, and it is not only okay but also necessary to engage in a two-sided conversation with the author.

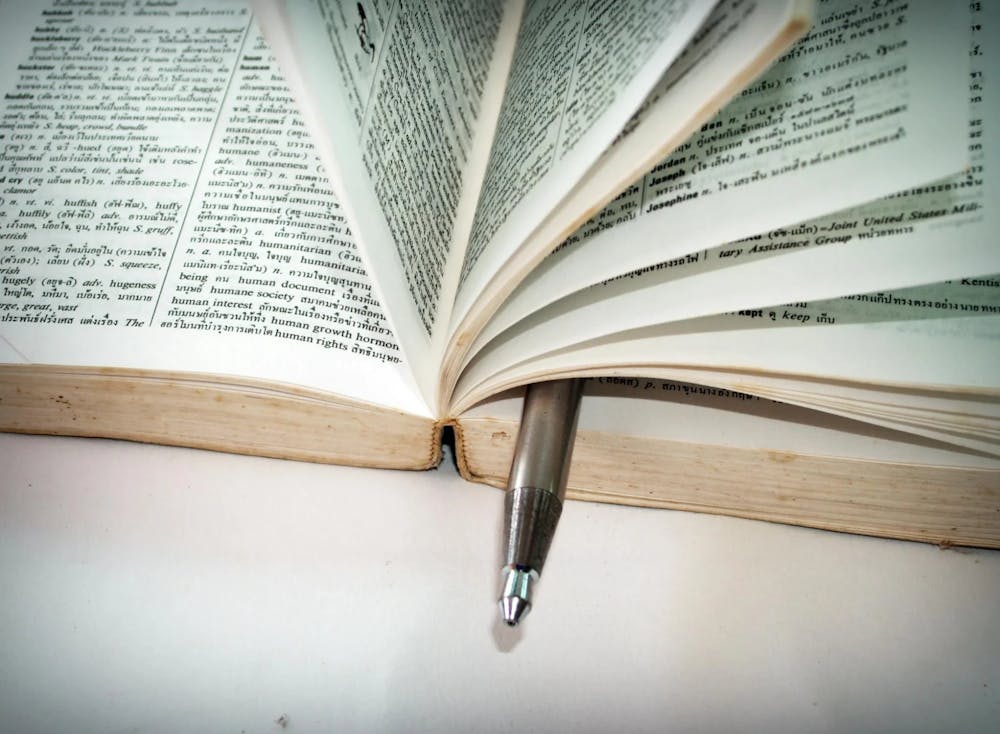

One way of active reading is to write in your books. While the idea of desecrating a piece of literature with a writing utensil might seem appalling, Mortimer J. Adler, a famed book-marker, states, “Marking up a book is not an act of mutilation but of love.” Adler says that writing in books, such as highlighting key points or writing notes in the margins, simulates a conversation between you and the author, helping you question their ideas and retain their knowledge better. I personally find this useful for navigating the dense academic materials encountered at Hopkins. Of course, this doesn’t give you the green light to go ahead and write in any book from the library; Adler still says that you should respect public books. He contends that a solution is to write down notes on a separate piece of paper and tuck them between the pages.

Another key aspect of active reading is questioning the author. Tung-Tien Sun defines this as “reading with specific questions in mind and search[ing] for answers.” He approaches active reading from a scientific angle, which is important to Hopkins students participating in research. Sun says that understanding the methodology and results of an experiment is crucial for proper comprehension of papers. He adds that while reading the text, you should formulate your own predictions and conclusions and compare them with the author’s results. If they’re different, then this could be an opportunity to identify where the study might have limitations or where further elaboration is needed. As someone involved in scientific research, this is a valuable way to scout out new areas for potential exploration or delve into new lines of inquiry.

Active reading encompasses all genres; whilst reading fiction, a reader should not be swept away by the story and engage in emotional reading, a shallow form of reading where one identifies themselves as a character in a book or treasures a book because it invokes nostalgia. This type of reading limits the book’s impact because you’re unable to focus on deeper themes that the author is trying to convey, and it limits exploration of the characters.

Vladimir Nabokov says that a superior approach would be knowing when to curb your imagination and enjoy the intricate world that the author has created. In Nabokov’s words, one should read with their “spine,” meaning that the literature should resonate on a deeper level, sending an instinctive tingle down your spine. I believe Nabokov’s advice is important for being able to enjoy both the artistic and writing talent of the author.

Finally, active reading can be achieved by reading with a pen in hand, which can be used as a weapon against florid or misleading writing. Although I think carrying around a pen while reading is a bit excessive, Tim Parks says that this allows a reader to catch flaws and errors that may otherwise fly over one’s head while engaging in passive reading. This is important in foreign languages, as an active reader will be able to notice illogicalities caused by mistranslations in text, ensuring that one understands an author’s original intent correctly.

I assure you that these simple steps empower any Hopkins student to improve their comprehension and critical thinking skills and gain a deeper appreciation for the text. This translates to saving effort by making sure you understand the text the first time around (because who enjoys revisiting the same paragraph fifty times?) and saving time by combining reading and note-taking. So, the next time you’re faced with a daunting pile of readings, make sure to utilize the active reading process and you might be surprised how much you can learn — and enjoy — while reading.

Eric Wang is a freshman majoring in Molecular and Cellular Biology from West Windsor, N.J.