Astronomers are fascinated with the early universe, peering outwards in space and backward in time to the very beginnings of the cosmos. Technological advancements help further their research, including the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which is specifically designed to see the earliest galaxies.

While observing one such galaxy, Hopkins doctoral candidate in Astronomy and Astrophysics Brian Welch found all his models pointing to a speck of light, a single star 50 times more massive than our sun: Earendel, the most distant star ever seen.

In an interview with The News-Letter, Welch discussed how the models guided him towards this discovery.

“As I was figuring out what the magnifications at different points along the galaxy were, the models I was working with kept pointing to this one piece being extremely magnified, by factors of 1000s, to the point that it was something much too small to be any sort of star cluster or any usual component of a galaxy,” he said.

His primary focus is gravitationally-lensed galaxies: distant galaxies whose light is distorted by large masses such that they are magnified from the perspective of Earth.

The classic analogy for this phenomenon is a rubber sheet with a bowling ball on it. An object, such as a marble, pushed along the distorted sheet will follow a curved path. In reality, massive objects like galaxy clusters redirect light from a source creating the appearance of multiple images or magnification. Welch cautions that this magnification is messy, more akin to looking through a wine bottle than a magnifying glass.

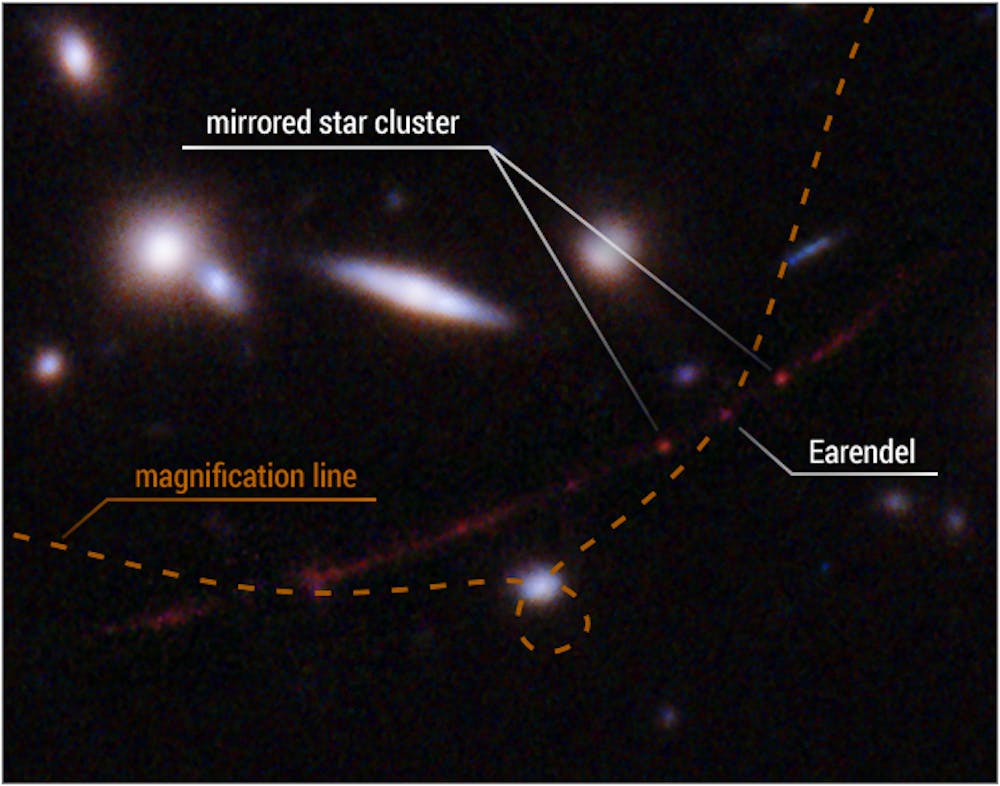

This distortion is clear from looking at the galaxy, WHL0137-zD1, containing Earendel (WHL0137-LS), which is stretched into a “Sunrise Arc.” Using four independent modeling techniques, Welch developed best-fit lensing cluster critical curves where the magnification was most extreme — a caustic. All four of these curves crossed the galactic arc within one-tenth of an inch of Earendel, enabling its light to be seen after 12.9 billion years.

“We're seeing the star as it was about 900 million years after the Big Bang. The universe back then was a really different place. There hadn't been generations of stars living, dying and spreading their heavier elements across the universe, so we expect the stars in the early universe to be much less enriched in heavier elements,” he said. “Studying one of these stars in detail, instead of looking at millions of them blended together, gives us a new way of looking at the early universe.”

Welch expressed his surprise at the interest in Earendel’s discovery, noting the many articles written since its announcement.

“It's definitely gotten a lot more attention than I expected,” he said. “I think the reason that it's gotten so much media coverage is because it’s a big superlative — the most distant star seen so far — that grabs media attention pretty well, and we ended up breaking the record by quite a bit.”

The previous farthest star, Icarus, was discovered in 2018 and sits 9 billion light-years from Earth. Earendel is not to be confused with the oldest known star, Methuselah, discovered in 2013. All three were discovered by the Hubble Space Telescope. Earendel was found in the Reionization Lensing Cluster Survey (RELICS) run by the Space Telescope Science Institute’s Dan Coe.

Before early stars like Earendel were kindled, the universe was in the Cosmic Dark Age—a period when no light was being produced. The birth of the first stars heralded the Cosmic Dawn, giving light to the burgeoning universe. Welch explained this light-bringing power is alluded to in the naming of Earendel, Old English for “morning star” and the name of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Eärendil, a mariner who sailed the heavens as a star on a never-ending voyage.

“[Earendel] was one of the first things that popped into my head, because the character Eärendil in The Silmarillion is an awesome character and literally becomes a star,” Welch said. “The [Old English connection was] great because the period of the universe we're looking at is referred to as the Cosmic Dawn, so the morning star of the Cosmic Dawn fit really well.”

The JWST will be re-examining Earendel to further study its properties and give even more understanding of the early universe.

In a press release from NASA, Welch reflected on the possibilities this discovery could yield.

“Studying Earendel will be a window into an era of the universe that we are unfamiliar with, but that led to everything we do know,” he said. “It’s like we’ve been reading a really interesting book, but we started with the second chapter, and now we will have a chance to see how it all got started.”