Over the course of the past year, researchers have found that residents of low-income, majority-Black neighborhoods in Baltimore and cities across the country are at a higher risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19.

For these neighborhoods in Baltimore, a common pattern emerges: They were almost all subjected to mid-20th century practices of housing segregation, including redlining and other racist policies.

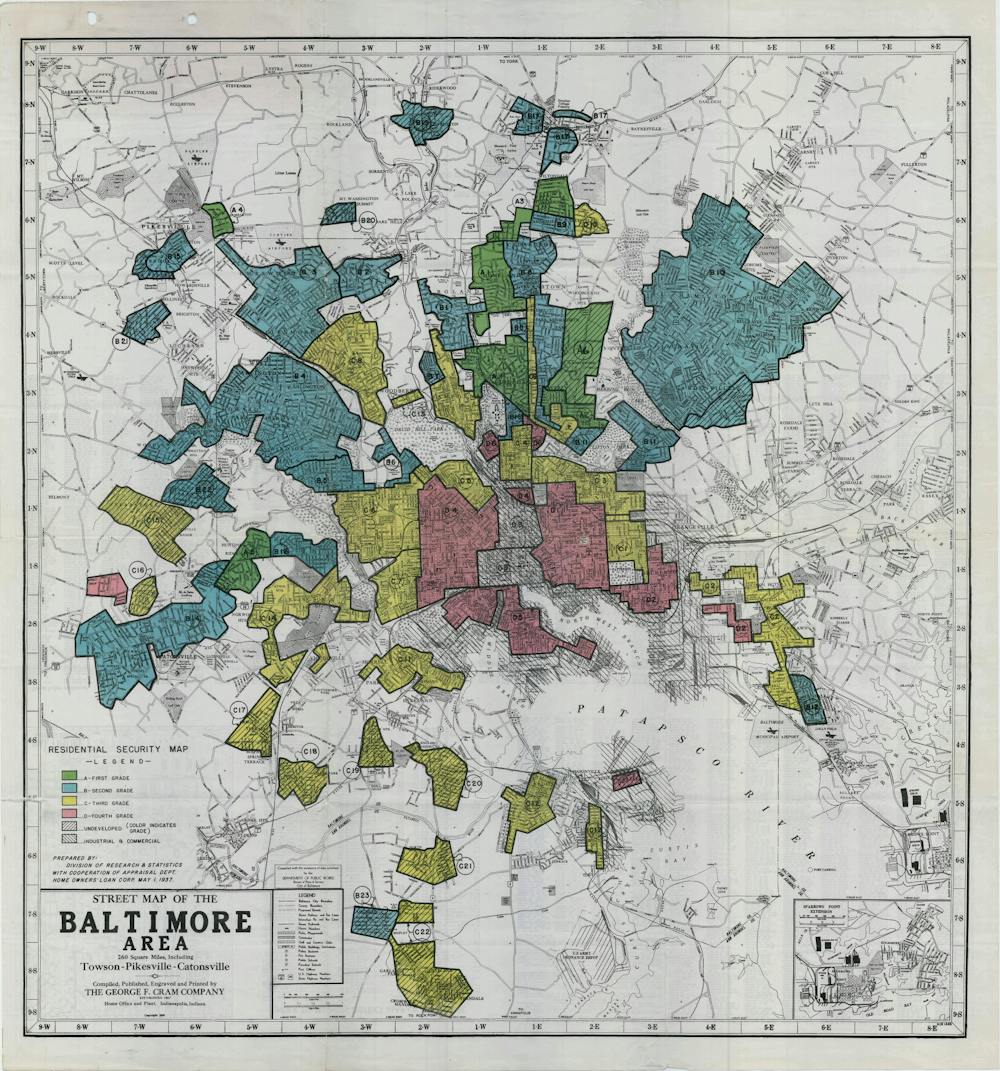

The history of redlining

In the 1930s, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) instituted redlining, which denied investment in neighborhoods deemed high risk. The risk was generally based on race or ethnicity. Members of minority groups were unable to secure housing loans outside of specially designated neighborhoods, whereas wealthier, white residents moved elsewhere.

Although racial discrimination in housing was banned in 1968, the impacts of these practices remain. The correlation between redlined neighborhoods and COVID-19 risk factors is merely one example of how these policies fueled pervasive inequities.

The city is still deeply divided between majority-Black and majority-white neighborhoods. To this day, Baltimore neighborhoods that were redlined have lower rates of homeownership, worse health outcomes and higher rates of poverty. Morgan State University Assistant Professor Lawrence Brown coined the terms the “White L” and the “Black Butterfly” to describe how white neighborhoods in Baltimore, which form the shape of an “L,” have structural advantages over Black ones, which form the wings of a butterfly.

Just north of campus, there are clear disparities between the east and west sides of the corner of York Road and Cold Spring Lane, including life expectancy and median household income. Last July, community activists and Hopkins students marched along York Road to protest these inequities.

COURTESY OF RUDY MALCOM

Baltimore’s Ordinance 610 in 1911 was a precursor to redlining across the country in the 1930s.

HOLC was created as part of the New Deal in 1933 and was a division of the government which issued bonds to purchase mortgage loans. The corporation is best known today for its maps of over 200 U.S. cities that indicated to mortgage lenders which neighborhoods were “safest” for investment. A blue neighborhood received an “A” grade, a red neighborhood a “D.” The term redlining was born from the red grades, which indicated “hazardous” status — a code for predominantly minority neighborhoods. While this often referred to high numbers of Jewish, Italian or immigrant populations, it almost always referred to high numbers of Black residents.

HOLC’s practices were the first official efforts to racially segregate housing nationwide. Yet Baltimore was familiar with the practice long before the 1930s, according to Alexander Lothstein, Museum Learning Manager at the Maryland Center for History & Culture.

“The idea of race-based housing segregation began in Baltimore, and a lot of other cities picked it up,” he said in an interview with The News-Letter.

In 1911, the mayor signed an ordinance that prohibited Black people from moving into certain “white” blocks. The reason for the policy was that a Black civil rights attorney had moved into a predominantly white neighborhood earlier that summer.

Though the first of its kind in the nation, the ordinance affirmed ideas that had already been blatantly present on both a national and local level, such as the “separate but equal” doctrine of the landmark Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson and the 1899 Baltimore mayoral campaign slogan, “This is a white man’s city.”

The Supreme Court declared race-based housing segregation unconstitutional in Buchanan v. Warley in 1917.

“It struck down civil government instituted racial segregation,” Lothstein said, “but it didn’t strike down private racial segregation.”

A new tactic emerged instead: blockbusting. Developers and real estate agents urged white residents to move out of their homes, operating on a fear of Black individuals moving in next door. They then turned around and sold the properties at higher rates to Black residents.

Rick Sadler, a former Bloomberg Fellow at the School of Public Health and a current assistant professor of public health at Michigan State University, noted that after World War II there was an even clearer distinction between white and Black neighborhoods in cities.

“The general pattern was that Black neighborhoods would be by factories, near polluted rivers, polluted ground. In older parts of cities, the housing would be in poor shape,” he said. “Linking the whole patterns of racial discrimination in employment and education, part of that was a self-fulfilling kind of outcome, where Black families welled up in these denser, poor neighborhoods.”

Race-based housing discrimination was finally outlawed on all fronts with the Fair Housing Act of 1968. But the effects on today are undeniable.

“There’s that generational wealth gap now where white families could start building wealth in new homes in the suburbs, starting in the ‘50s, or ‘40s even,” Sadler said. “That was basically completely locked out to African Americans until the late ‘60s, early ‘70s.”

COURTESY OF RUDY MALCOM

The Hospital is a bright white square in a sea of red on the HOLC’s residential security map of Baltimore.

The University’s role in redlining

The Baltimore City Council officially passed Ordinance 610 in 1911, establishing a strict, city-wide housing segregation law. The bill included a report titled “Housing Conditions in Baltimore,” by Janet Kemp, which suggested that certain residencies, particularly Black-owned properties, be condemned.

Kemp’s report was initiated by the Charity Organization Society, a group that intended to solve social problems in Baltimore and was founded by former University President Daniel Coit Gilman.

In her analysis, Kemp distinguishes between white “tenement districts” and Black “alley districts,” referring to the latter as “slums.” Racism underpinned her analysis and ultimately the ordinance that became law.

Ordinance 610 was a precursor to nationwide redlining in the 1930s. Hopkins Hospital is located in what was once deemed a “D” neighborhood by HOLC. All of the surrounding neighborhoods — with the exception of the ungraded Greenmount Cemetery, Patterson Park and harbor docks — were graded either C or D.

HOLC listed a “proximity to employment, industrial and commercial” as an aspect of the area’s “Favorable Influences” and a “heavy concentration of foreigners” under “Detrimental Influences.” The area description detailed that foreigners included Italians and an “Infiltration of Negro,” each group comprising a quarter of the community.

The Hospital itself, however, is not subject to a D grade. Like the greenery surrounding the neighborhood, which escapes a rating, the Hospital is bright white square in a sea of red.

Lothstein explained that this was HOLC’s attempt to mark the Hospital as a separate institution. He stated that because the plot wasn’t a home that could be considered for rent, it was left out and marked as a decent employment opportunity.

Under Clarifying Remarks, surrounding properties are described as “better than average” and having “considerable desirability.” This characterization reinforces the ongoing perception that Hopkins is an institution that thrives at the expense of its neighbors, that Hopkins sits in Baltimore but isn’t a part of it.

COURTESY OF KATY WILNER

Housing segregation in Baltimore is in part the legacy of Gilman Hall’s namesake.

In an interview about his book The Ghosts of Johns Hopkins, Baltimore historian Antero Pietila discussed how Hopkins had once considered relocating from East Baltimore to Columbia. It chose not to do so because “it would not have had ready access to clinical material, people with whom it could experiment — whereas in East Baltimore, in poorer black East Baltimore, there was lots of clinical material.”

Pietila also describes how the University demolished Black residents’ homes to make dormitories for workers. This action echoes the idea from the HOLC map’s Clarifying Remarks that the neighborhoods around the Hospital have good qualities, but only if their current residents are removed.

Nneka Nnamdi, the founder of Fight Blight Bmore, elaborated on the University’s negative impact on the city. Fight Blight Bmore works to remedy blight, an umbrella term for vacant and underutilized properties in neighborhoods lacking adequate resources.

“There is a straight line from redlined communities to blighted communities today,” she said. “[The University] is using its power as an anchor institution to displace the people who live in the footprint, making people's housing insecure and damaging communities.”

She detailed the physical and psychosocial impacts of living in areas that have been affected by things like deindustrialization, white flight and urban renewal.

“As a child when you look at communities that are in poor condition you start to wonder, ‘What is wrong with me? What is wrong with us?’ Especially when three blocks over, on the other side of town, there are parts of your city that don’t look like that.”

Nnamdi urged Hopkins students to research Baltimore in a way that does not “pathologize” its residents or their conditions.

Debra Furr-Holden, former professor at the Bloomberg School of Public Health and current colleague of Sadler at Michigan State, investigates health equity and disparities.

She pointed out that Hopkins signed a charter with the city in 2009, stating that it would provide medical care for the Hospital’s surrounding ZIP codes. However, Furr-Holden noted that the distrust between these communities and the Hospital runs deep.

“The cost of primary care relative to the emergency department is crippling for some people,” she said. “The University has to write off annually a very large amount of medical expenses from people who come to the emergency department who simply don't have the ability to pay.”

Liz Vandendriessche, assistant director of Public Relations, Media Relations, and Corporate Communications at the Hospital, underscored these efforts in an email to The News-Letter.

“At all points in that process, patients are encouraged to speak with financial counselors and patient financial services associates; their bills will be forgiven if they can show financial hardship or inability to pay,” she wrote. “To note, approximately one year ago, Johns Hopkins placed a pause on lawsuits related to patient debt collections.”

Despite these actions, Hopkins will always have to contend with its physical location in the city — even if it didn’t cause the housing discrimination itself.

COURTESY OF RUDY MALCOM

The University is acknowledging its racist legacy and partnering with community groups.

The legacy of redlining

Studies have also highlighted the health impacts of redlining. Baltimore is one of many cities that experience urban heat islands, where redlined districts are, on average, one to seven degrees hotter than predominantly white neighborhoods.

Redlining has also severely hindered property ownership, a key component of wealth-building strategy. Throughout history, residents in redlined areas have been denied loans from banks, instead being targeted by predatory loan services with high interest rates. As recently as 2012, Wells Fargo entered into a $184.3 million settlement after the U.S. Department of Justice found 34,000 instances of the bank issuing higher cost loans to Black and Latino people.

Additionally, speculators continue to purchase homes in redlined areas, only to turn around and rent them to residents at inflated rates. This has led, in part, to a lack of development initiatives in many neighborhoods in Baltimore; Inner Harbor, which was redlined in the 1930s, is a rare exception.

The stagnancy in development is disheartening, but Baltimore has made efforts to address the underlying inequities that cause this lull.

The Baltimore City Office for Equity and Civil Rights began hosting an annual Fair Housing Festival in 2020. The event, which features performances, student artwork displays and in-person and virtual historic galleries, celebrates the 1968 passage of the Fair Housing Act.

Lauren Jackson, an investigator with the Community Relations Commission within the Office for Equity and Civil Rights, hopes that the event will educate Baltimoreans and encourage them to speak up about their own neighborhoods. Most fair housing complaints, she said, come from people with disabilities and people of color.

“Our hope is that after they see these stories… that they’ll come forward and tell us their stories about housing discrimination, because that’s the ultimate goal,” she said. “We just know that folks either don’t realize it’s happening, because of the way that housing discrimination has changed, or they don’t know who to turn to.”

The federal government has also taking several steps to rectify the past through efforts like the Choice Neighborhoods program. Communities across the country, such as Baltimore’s Perkins Somerset Oldtown, receive grants from Housing and Urban Development to improve housing, schools and vacant properties.

Rick Sadler from Michigan State pointed out that the program seeks to improve the current situation of neighborhoods without making the same errors of former public housing projects. He explained that by improving housing within a city, there is a net positive effect on both families and the city.

“Kids perform better. Kids have less behavioral issues. Parents have more employment options,” he said.

The University has also attempted to address this issue through its urban research center 21st Century Cities Initiative (21CC). Mac McComas, a program manager at the 21CC, mentioned how in 2015, the University created HopkinsLocal, which aims to connect local Baltimore residents with economic opportunities and invest in local and minority-owned businesses.

Furr-Holden praised the University’s efforts to address the city’s continued racial divide through elevating partnerships with communities, noting her appreciation for the institution’s acknowledgment of its role in perpetuating inequity. While she is optimistic, Furr-Holden explained that Baltimore residents are the only ones who can say when Hopkins has done enough to rectify its past.

“Is it enough? I don’t know,“ she said. “I think to answer that question, we have to ask the community.”

Nneka Nnamdi stressed the importance of centering the Baltimore community going forward.

“We know that people with the lived experience of a particular problem will have the most sustainable and equitable solution to it,” she said.

Elizabeth Raphael contributed reporting to this article.

FILE PHOTO

Community activists and Hopkins students marched along York Road in July to highlight racial disparities just north of campus.