Citizen Kane is hailed as the greatest film of all time. Mank, in one of the most unexpected and idiosyncratic ways possible, tells an equally remarkable story of the process behind the film. Helmed by director David Fincher and written by his late father Jack Fincher, Mank had been in the works for thirty years prior to its December release on Netflix.

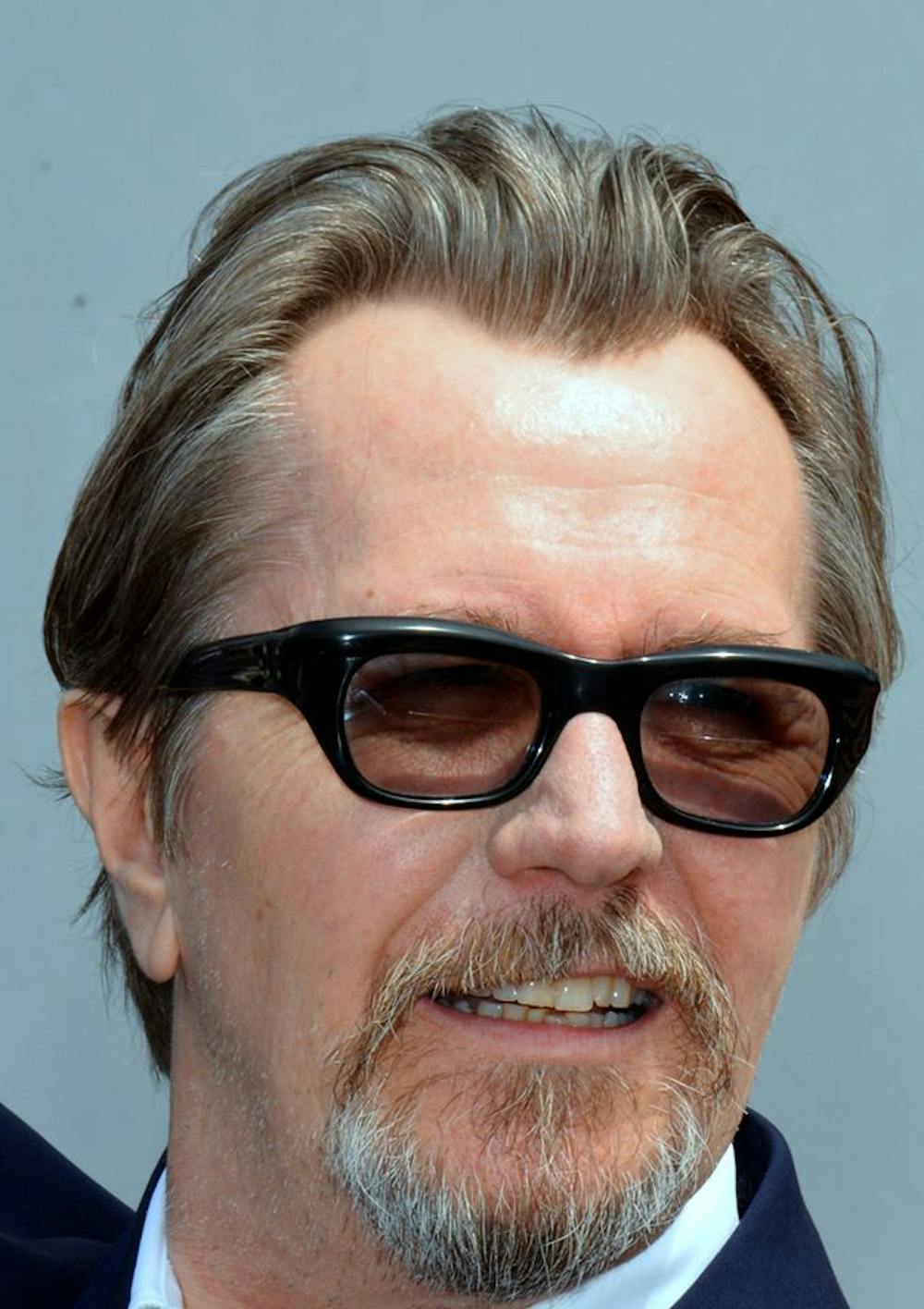

The first unorthodox element comes in the form of Fincher’s choice of narrative. As opposed to a focus on the director Orson Welles, at the center of the story is the great screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz — known as Mank. He is delightfully played by Gary Oldman, who effortlessly captures the characteristic wry wit of the man who co-wrote Citizen Kane with Welles.

It quickly becomes evident that Mank isn’t so much plot-driven as it is an observation of the happenings of the time. It can be best described as a central storyline set in 1940, interlaced with flashbacks from the ‘30s and onwards. The said storyline which the flashbacks revolve around is Mank’s race to finish the screenplay for Citizen Kane in 60 days, as demanded by the then-24-year-old prodigy Welles.

A broken leg — thanks to a very avoidable car accident — has Mank cooped up in a guest ranch in Victorville, which is where he begins to write. With his secretary Rita Alexander (Lily Collins) taking dictation, he spends the majority of his time in bed. And when he’s not working, he’s grumbling, usually affectionately, about something — likely along the lines of getting a drink.

Soon his alcoholism proves to be a major hindrance to his writing, much to the disapproval of Rita and his editor-turned-supervisor John Houseman (Sam Troughton). Concerns with the draft of the screenplay are brought up: its nonlinear nature, leaping around in time like “Mexican jumping beans,” as well as the resemblance of the protagonist to William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance), a newspaper tycoon.

Calls from Welles come from time to time, but Mank is shown to be solely responsible for the creation of Citizen Kane. Furthermore, the cinematic masterpiece appears to have firm roots in reality, taking a great deal of inspiration not only from Mank’s knowledge of Hearst but his own somewhat cynical view of power.

Throughout, we get glimpses into Mank’s world — his marriage with wife Sara (Tuppence Middleton), his friendship with actress Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried) and his acquaintance with Hearst. We also subtly get glimpses into his character. Unabashed retorts during dinner parties and ramblings with studio executives show Mank to be his own man, impervious to and, perhaps even disillusioned by, the glitter of Tinseltown.

All the while, Mank serves as an introduction to the studio system and the pronounced role of politics in Old Hollywood. The socialist Upton Sinclair is repeatedly mentioned, as we find out that Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) is producing propaganda to discredit him. Behind this endeavor are key figures like MGM co-founder Louis B. Mayer and producer Irving Thalberg. This subplot largely unfolds through the flashbacks, and Fincher makes a point to showcase the conservatism of Hollywood along with its power and corruption.

The great care taken to develop the story is also applied to how it’s told. As a homage to cinematographer Gregg Toland’s work in Citizen Kane, the film is shot in its entirety in striking black and white. In fact, nearly everything — from lighting to transitions to sound — is eerily period-accurate. As a consequence, it’s near impossible not to be enveloped into Fincher’s world, absorbed in the rhythmic ups and downs of Mank’s distinctive manner of speaking.

Despite these efforts, it can still at times be alienating for audiences that are not quite to the level of elite film buffs or even those not well-versed in 1930s American politics. The film moves quickly and purposefully, and the only direct explanation it takes time to give is Welles’ deal with RKO Pictures that granted him absolute creative autonomy. In other words, Mank is a niche film and seems happy to remain that way.

By its triumphant ending, it’s clear that Fincher has crafted an absorbing, touching portrait of the entertainment industry. By placing the spotlight on the screenwriter, he too has presented an argument against the concept of auteurism — providing his own take on the long-debated question of Welles’ contribution to Citizen Kane. And disguised within all this is a relevant portrayal of the political landscape of decades past.

As the legendary screenwriter remarks at one point, “You cannot capture a man’s entire life in two hours. All you can hope is to leave the impression of one.” And Mank certainly leaves quite an impression.