Although many have visited the Hutzler Reading Room in Gilman Hall, not quite as many have paid attention to what’s on the stained glass windows.

In fact, each panel displays a renowned European printing press during the Renaissance period.

Why shed light on the progress of knowledge by commemorating the printing press, I wondered.

Recently, the Dr. Elliott and Eileen Hinkes Collection of Rare Books in the History of Scientific Discovery answered this inquiry.

Dr. Elliot Hinkes obtained both his bachelor’s and medical degrees from Hopkins. Though he became a collector by accident, Dr. Hinkes was wholeheartedly devoted to his collection. He was exceedingly careful in obtaining the finest available copies of books he sought and never halted his academic pursuits so that he was well-versed enough on the subject matter of the materials he acquired.

In the 2000s, Dr. Hinkes generously donated his collection to Hopkins, which enabled students and faculty to study its contents on a regular and active basis.

The Hinkes collection contains roughly 300 volumes, dating from the late-15th to the mid-20th century. It meticulously maps human progression from the Scientific Revolution to the modern age without any significant leaps. This is all thanks to Dr. Hinkes’ focus on the true “Eureka” moments of scientific history. The Hinkes collection illustrates how the invention of the printing press in Europe facilitated the burst of knowledge at the dawn of the Renaissance.

Included in the Hinkes collection is a leaf from the Gutenberg Bible, one of the first books in the West to ever have been printed using movable type.

German inventor Johannes Gutenberg combined oil-based ink, adjustable molds and mechanical movable type in his invention.

Gutenberg’s contemporaries and immediate successors were quick to take advantage of this system that allowed economically viable production of books. Among them was Austrian court astronomer Georg von Peurbach, and the Hinkes collection includes one of his most popular works: Tabulae Eclypsium.

Peurbach, after observing a lunar eclipse occurring eight minutes earlier than predicted by the Alphonsine Table, the standard planetary table at his time, went on the refine the old table.

Although Peurbach himself was an advocate for geocentrism, later generations of astronomers — including Tycho Brache and Johannes Kepler — used his data in Tabulae Eclypsium to calculate the solar and lunar longitude and latitude, anomaly and parallax, which served as evidence for heliocentrism.

Another remarkable work the collection includes is Johann Bayer’s magnificently illustrated Uranometria, which is truly a masterpiece of the Printing Revolution.

On its allegorical title page, “mother earth” — the goddess Cybele — charges through the celestial heavens on her lion chariots. On either side, Apollo and Diana are enthroned above Atlas, the ancient master of astronomy, and Hercules, the first student of the heavens. Down below, the author’s home city Augsburg is depicted below the zodiac figure of the constellation of Capricorn.

Although Bayer only recorded the constellations visible to the naked eye, his methodology of assigning Greek letters according to the brightness of stars, as evident in this depiction of the constellation Cetus, successfully reduced confusions.

Works of earlier astronomers, preserved by the technology of print, served as a jumping-off point for successors during the Renaissance to resolve the relationship between the heavens and earth. Nicolaus Copernicus’ De Revolutionibus, in which he presents the heliocentric system, is almost synonymous to the Scientific Revolution itself. The Hinkes collection includes an uncut, unsewn and unbound copy of it produced in 1566.

Although Copernicus resolved issues that the geocentric system had failed to account for, it took a gradual succession of astronomers, including Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei to solidify the foundation of heliocentrism.

Although Brahe only made observations using the naked eye with the assistance of instruments he built, he was one of the first to acknowledge the value of monitoring the quality and fidelity of records and illustrations.

Brahe owned a private group of printers and pressmen, and his collaborator and successor Kepler also played a role in compiling his observations. Kepler, despite being a true empiricist himself, greatly relied on Brahe’s records to develop his planetary laws.

The Hinkes collection includes a copy of Kepler’s Mysterium Cosmographicum which features an intricate illustration of geometric shapes inscribing one another that was Kepler’s first correct attempt at describing the solar system geometrically.

The Hinkes collection also owns several of Kepler’s later works, which he was likely to have made copies of and sent to noted astronomers, such as Galileo, who inherited the spirit of making meticulous observations and designing replicable experiments.

Many of Galileo’s published works included precise illustrations of specific instruments he used, offering fellow academics the opportunity to replicate experiments, confirm findings and make other discoveries.

The process of making scientific discoveries, starting from this era, began to resemble modern day methodologies. Starting with the era of Brahe, Kepler and Galileo, and facilitated by the use of printing press, scientific discovery seems to have taken an aggressive turn, towards a mechanistic understanding of the natural world.

This way of investigating and viewing the world reached its heights in the Newtonian Revolution at the end of the 17th century. The printing press had woven European scientists together and helped to accelerate scientific discoveries at an unprecedented rate.

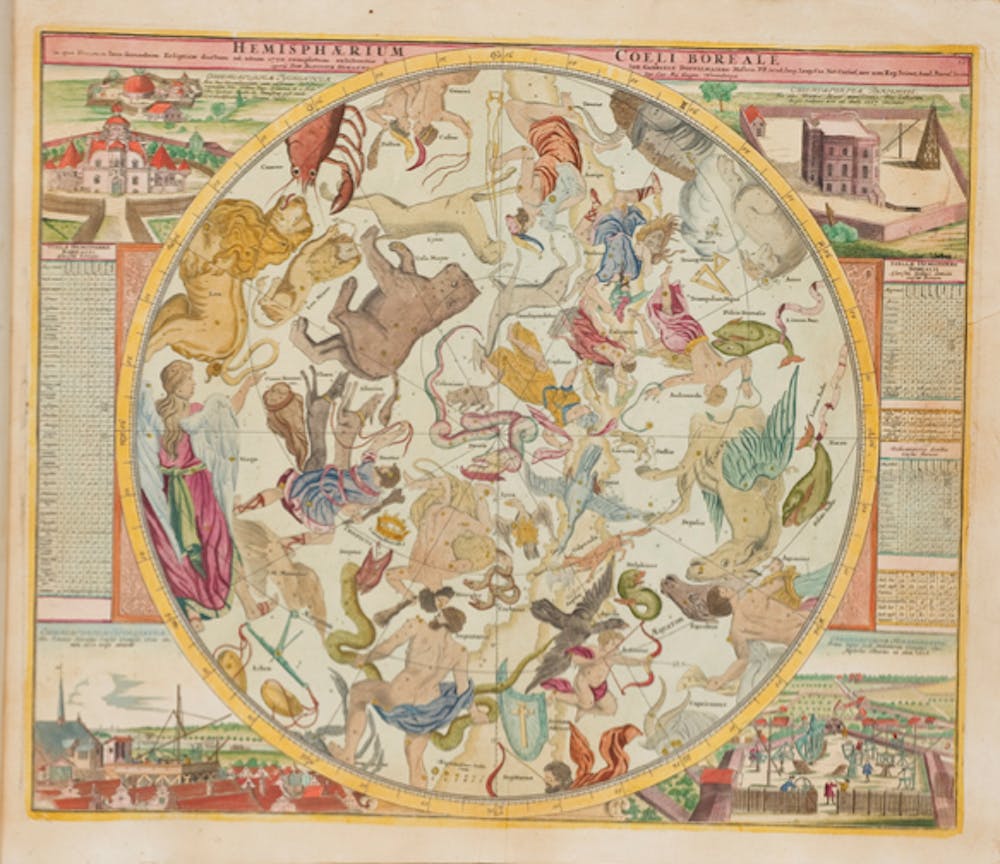

One of the pieces from the Hinkes collection offers a perfect conclusion to those centuries worth of scientific progress - Johann Doppelmayr’s Atlas Coelestis. In vivid juxtaposition to the works of Copernicus, Brahe and Kepler, which stand out due to their scientific value, Atlas is one of the finest color prints to survive to this day.

The plates that the collection preserves present elegant star charts overlaid with figures from classic mythology. On each side, Doppelmayr also pays tribute to the places where great discoveries were made, including Brahe’s laboratory on the Danish island of Hven, the observatory of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris and the English Royal Observatory at Greenwich.

Doppelmayr’s work puts the celestial heavens in the context of the institutions that would go on to transform scientific discoveries. And it seems rather fitting that, along with other pieces of the Hinkes collection, it now resides here in America’s first embodiment of modern European research universities.