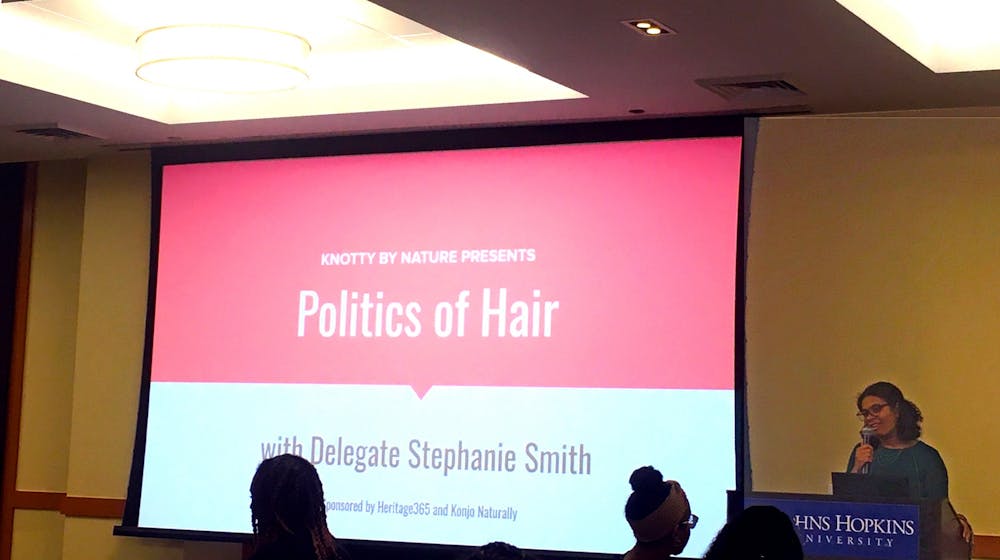

Delegate Stephanie Smith explored the government’s nationwide efforts to ban hair discrimination in a presentation titled “Politics of Hair,” hosted by Knotty by Nature, a student group on campus that seeks to empower natural hair, in Charles Commons on Tuesday. Smith represents the 45th State Legislative District in the Maryland House of Delegates and serves on the Legislative Black Caucus.

The event was co-sponsored by Heritage365 and Konjo Naturally. Heritage365 is an initiative of the Office of Multicultural Affairs that seeks to celebrate cultural heritage year-round. Konjo Naturally is a company that distributes customized boxes of hair products that are naturally produced by black-owned businesses.

Smith primarily discussed the Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair (CROWN) Act, which Montgomery County unanimously passed earlier this month, becoming the first county in the U.S. to ban discrimination on the basis of a person’s natural hairstyle.

According to Smith, the natural hair rights movement began after a controversial Dove ad in 2017 that featured a black woman becoming white as she washed her body. An African American Dove executive, Smith explained, urged the company to invest in black organizations, leading Dove to support the CROWN Act, which has since been introduced and passed in other states.

“What’s really important about this whole effort is that it’s bringing together academics and social activists, people young and old, and policymakers to take a more aggressive stance against what anti-blackness means in this context,” Smith said.

Before Smith spoke, Zainab Jimoh, co-president and co-founder of Knotty by Nature, recounted the history of hair discrimination.

“Once our ancestors were brought from Africa, one of the few things they were forced to do was shave their head. This was a sign of dehumanization in an effort to strip them of their identity and culture,” she said.

Jimoh mentioned that the Tignon Law, passed in 1786, prohibited Creole women of color from dressing elegantly and forced them to wear a head covering to show that they belonged to the slave class, regardless of whether or not they were enslaved.

She added that, although the Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned racial discrimination in schools, employment and public places, it did not prevent hair discrimination because it was left to the courts to decide what constituted racial discrimination.

Jimoh also discussed Jenkins v. Blue Cross Mutual Hospital Insurance Inc., where Beverly Jenkins argued that she was denied a promotion because of her Afro. Although she won the lawsuit, Jimoh noted that the precedent had little impact on future laws.

“This was the very first time that anyone with natural hair was given a piece of legislation to be allowed their natural hair,” Jimoh said.

In 2006, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a federal agency, created a compliance manual that protected against workplace discrimination based on a person’s physical characteristics associated with race.

However, there are still many cases, Jimoh said, where individuals face discrimination because of their natural hair.

“Hair discrimination is not pertinent to one specific person. Males and females, no matter the age, even as young as three years old, are being discriminated against,” she said. “A third of the residents of Maryland are black, and yet this does not mean that black people have all the opportunities that you think they should.”

Sophomore Adelle Thompson underscored the value of Smith’s presentation in an interview with The News-Letter.

“I’m a black woman who wears her hair natural. It’s one of the first things that people see about me, and it’s something that everybody always comments on,” she said. “I haven’t faced hair discrimination, but people have made extremely negative comments about my hair. I remember one kid at my high school said that I shouldn’t be able to go to prom with my hair.”

Sophomore Lani Banner told The News-Letter that she has never experienced hair discrimination. She expressed her support of the CROWN Act, but noted that she disagreed with Smith’s extending the definition of race to protective styling. Protective styling is type of styling where hair is not “loose,” protecting hair ends.

“The CROWN Act includes protective styling, which they are trying to argue that this Act will be an extension of race. Protective styling itself is not an extension of race, so they may just have to craft a different argument, but I do feel protective styling should be included,” she said.

Sophomore Gurjot Chand emphasized the need for the CROWN Act.

“To think that it’s still a struggle is upsetting in the sense that it’s just starting to get talked about. Not being in the black community, I think it’s also important to have others here as well because it is a fight where everybody is in it,” he said.

Similarly, Smith concluded by encouraging audience members to use their platform and advocate for the CROWN Act.

According to Smith, even politicians such as herself are not immune from hair discrimination, and worry about whether they will be taken seriously in their work because of their physical appearance.

“Just the way you were brought into this Earth, from the crown of your head to the sole of your feet, there is nothing deficient about you,” she said. “You were made the way you were supposed to be.”