As part of the Virginia Fox Stern Center Lecture Series, Sonja Drimmer, an associate professor of Medieval Art and Architecture at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, gave a talk entitled “Provisional Vision: Posters and Politics in Fifteenth-Century England“ on Tuesday.

The lecture was held in the Macksey Seminar Room in Brody Learning Commons.

Drimmer explained that she planned to use this opportunity to express her thoughts, as she is currently working on her second monograph, on objects largely overlooked by art historians because they are not considered “good” art.

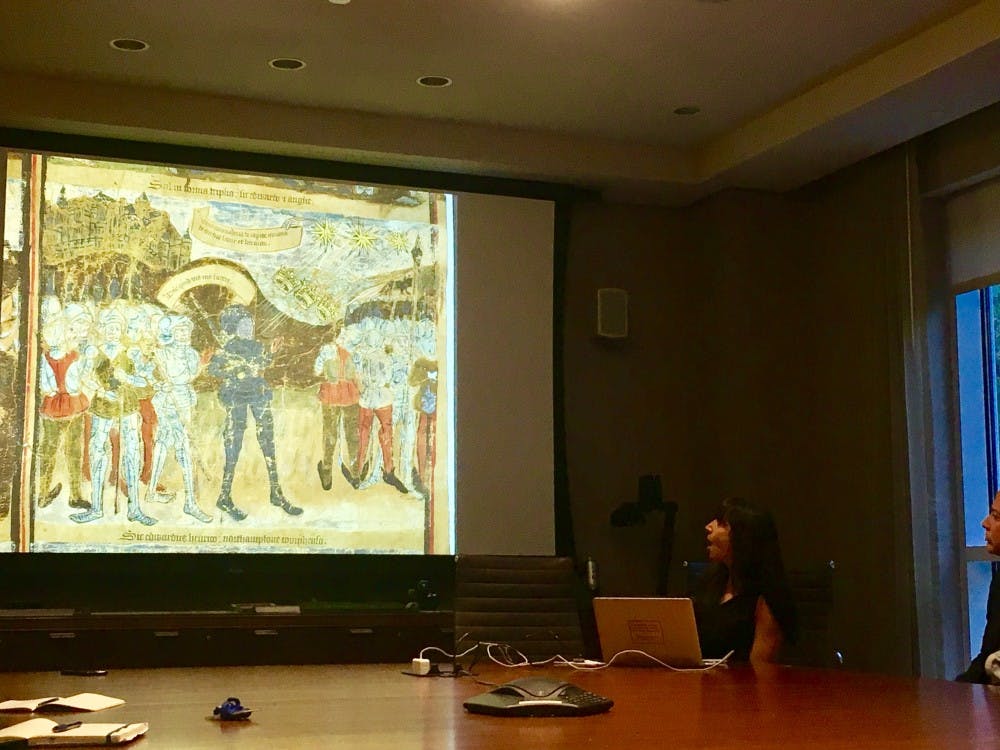

Her main topic was the manuscript roll of Edward IV. The famous piece of parchment has remained an anomaly within the art history field.

The roll was inspired by the final battle of the War of the Roses between the house of Lancaster and the house of York, headed by Edward IV, Earl of March, before he became king.

Now located in the British Library, historians still do not know who created it or from when it originates.

Drimmer proposed two ways to view the roll — the political and the visual.

The political perspective focuses on recognizing competing claims of what a legitimate government is to the public. The visual perspective, on the other hand, represents wishful thinking regarding ideals of a regular person.

“So these two conditions — recognizing competition and wishful thinking — describe a vision that conceptualizes the here and now as if it were or might be otherwise,” Drimmer said.

Drimmer went on to discuss the three main parts of the roll. She explained that the lowest part of the scroll depicts the genetic symbolism of the Yorkist family tree.

“The family tree mimics the Tree of Jesse, which depicts the lineage of Jesus Christ. The very top of the family tree shows the infamous scene between Henry VI of the Lancaster house and Edward IV of the York house in their final battle scene, as Edward IV takes on his final obstacle before gaining the throne,” she said.

The middle part of the roll, Drimmer said, is filled with images of typologies between the Old Testament and the New Testament.

The top part of the roll depicts Edward IV’s final assumption to the throne. The images portray Edward becoming the alpha and omega, existing as an omnipotent force.

Drimmer also explained that the artist has portrayed Edward IV to seemingly mimic Christ’s powers and abilities as the new King of England. She also discussed the roll’s connection to politics and religion.

“The difference between political and religious visionary experience is expressed clearly here,” she said.

She went on to discuss the differences between religious and political typology.

“Religious typology demands that we accept that Christ is a prophet and is a king. But political typology asks you to think of Edward as if he were the new Moses and be compelled by that proposition,“ Drimmer said.

Drimmer stated that she has always dreamed about finally being able to end her lecture with an answer to the many mysteries of Edward IV’s roll.

But she explained that since she didn’t have concrete answers, she would end her talk by instead giving her hypotheses on the enigma.

“What I suspect is that it was placed in the interior of a large public space, perhaps a city’s guild wall. And in this capacity, it would have altered a communal space, transforming its signifying system with the factual vision that imagines Edward as if he were Moses, David, Joshua, Saul, Constantine and even Christ himself,“ Drimmer said. “Questions of what this object is, how it was displayed and how it was perceived are all in dialogue and inseparable.”

History graduate student Alex Yang read one of Drimmer’s articles in class. He explained that, due to his interest in popular forms of politics in early modern Europe, the lecture topic was very relevant to him.

“One of the really interesting things in studying the meaning of early modern art or just systems in general that are not our own is that it reminds us there are a lot of different things that make meaning that we do not think about necessarily nowadays,” Yang said.

Another graduate student in the Department of History, Arthur Lee, learned of the lecture series through an email from the Hopkins history department.

Lee said that he has always been very interested in the histories of different books and wanted to learn more through Drimmer’s discussion on manuscripts and typology rolls.

“I really appreciated the creative attempts to figure out what the object was. I thought that the informed speculation there was very interesting,“ Lee said. “When we’re trying to study the history of books and printing and publication, it is easy to think that we know what a book is.”

Lee continued, explaining how physical artifacts bring new perspectives to the histories of books.

“Objects like these are helpful in making us think harder about the differences between books and things that look really similar,” he said.

Mitchell Merback, a professor in the History of Art department, already knew Drimmer’s work and came to her talk to learn more about her research, confident that it was going to be a great lecture.

Merback was very impressed with Drimmer’s ability to convey complicated concepts to an audience of students.

“I heard a very sophisticated analysis of some very complex imagery that involves words and pictures,” Merback said.

Merback added how art historians in particular have unique takes that contextualize things for audiences.

“I’m always interested in that and the possibility that it was set out for a specific audience. It is really good when art historians can describe how an audience would have seen it in light of its specific context,” she said.