The entrance to the exhibition City People: Black Baltimore in the Photographs of John Clark Mayden sits to the left of Peabody’s entrance.

The room is small. Photographs grouped in couples and triples line the walls, all black and white, all centered around the black population of Baltimore as their subjects.

The pieces are in loosely related groups — in some, the bodies mimic and melt into the architecture. In others, subjects exist behind barriers and screens.

Some play with lapses of time, comment on religion, experiment with silhouettes or examine American values. There are allusions to the self, the self through the camera lens, to the inevitable process of aging, to ways of co-living and to action versus immobility.

Form and content interact. Interspersed are video recordings with the artist, historical analysis of the relationship between photography and African Americans and a map hanging on the wall at the end of the exhibit. Here visitors are asked to mark where they live in Baltimore and places that are important to them — a story of a city spreads out in blue and orange dots.

All foot traffic into the building without a Hopkins or Peabody ID is directed through the one-room exhibit. In fact during the hour or so I spent moving around the room, most of my fellow viewers seemed to have paused en route to the main, soaring hall of the library.

It seems as though the composition of the exhibition itself and its location adjacent to the library, is mimetic of the works in the exhibition. As viewers walk through the room to get to another destination, they get caught by a compelling image or a general curiosity that mirrors the methodology and practice of the photographer.

John Clark Mayden has spent close to 50 years walking the streets of Baltimore, photographing Baltimoreans as they go about their day-to-day lives.

In the video interview playing above a display of contact paper and aging cameras, Mayden relays that forms of transportation other than walking, such as public transportation or driving, limited his access to the city.

After stepping outside his previous methods of movement, which were often relegated by predetermined city routes or his own comfort, Mayden found that he had limited much of his interaction with different neighborhoods in Baltimore.

He used walking as a way to interact with spaces in Baltimore and to remove boundaries separating him from the daily life of ordinary people without even having recognized himself.

Having integrated and immersed himself into the city over the last 40 years, Mayden now invites the public into the collected fragments of his journey.

Moving in tandem with this singular expedition into the lives of the people of Baltimore is an examination of the history of photography and the relation between photography and the lives of black people in America.

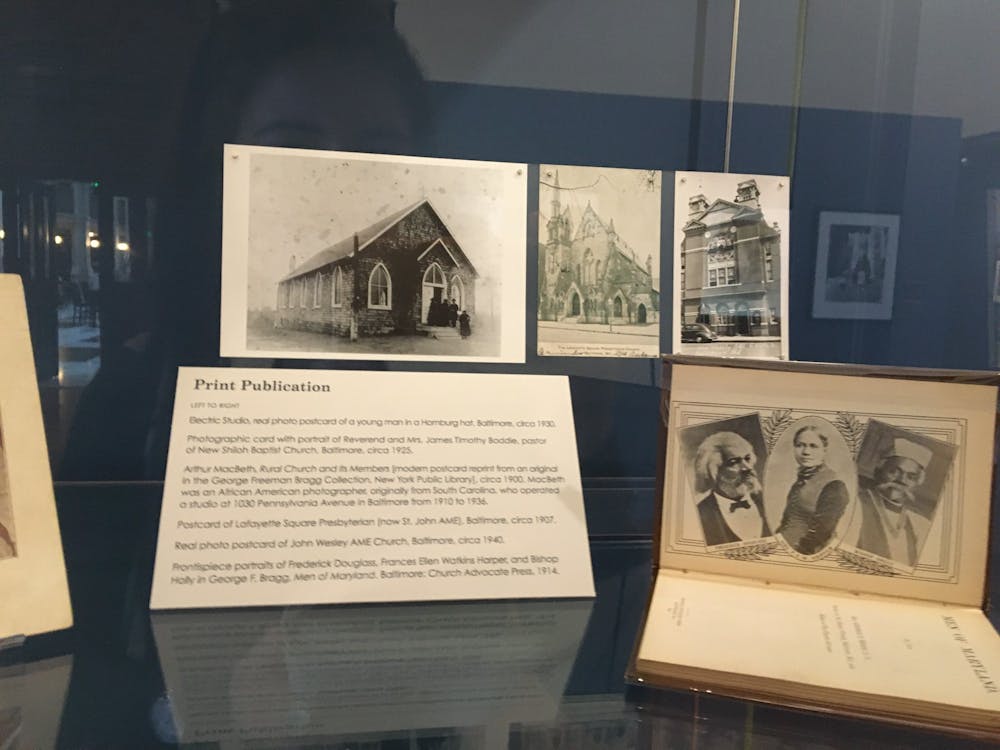

Along the walls of the exhibit is a collection of photographs of black people dating back as early as the 1800s, a reminder to the viewer of a history that is often not seen and has not been accounted for because — historically — social discourse has been dominated and defined by images that center on white people.

The signage accompanying this display discusses how photography and the subsequent relative ease of circulating images cheaply equalized the power of self-directed portraits, bringing autonomy to populations misrepresented and maligned in the media.

More personally, photography was a way to culturally solidify the family, to share and keep images of loved ones; in other words, to build a history and an identity that lasted even if society as a whole would not bear witness.

So much of history is dictated by those who have the power to control images of people, and this exhibit is a stark reminder that despite all our efforts today toward diversity in relation to image and representation, we simply cannot move past history.

With this in mind, the exhibit is based in the explorations of black existence in relation to the camera, while also moving beyond a simple effort of representation.

It is a testament to Baltimore’s community and reality, an exhibit that tracks an artistic talent and growth and a room that challenges the viewer to find their place.