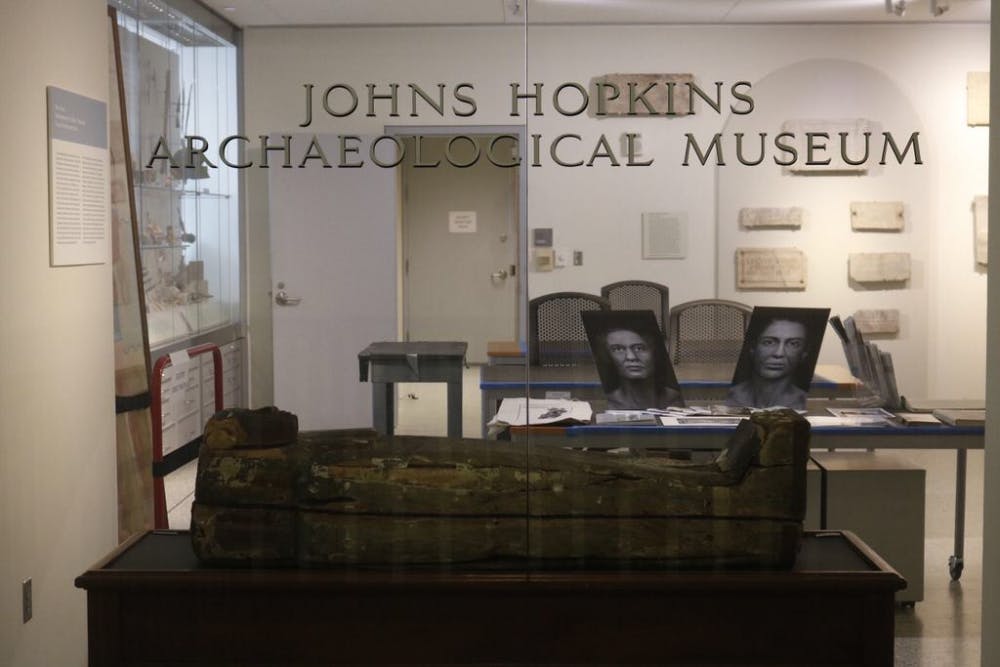

Stepping into the Hopkins Archaeological Museum, located in the heart of Gilman Hall, your eyes are sure to settle on two individuals: the Goucher Mummy and the Cohen Mummy. How can we understand the identity and humanity of these two ancient women? Beginning in 2016 and completed in 2018, Who Am I? Remembering the Dead Through Facial Reconstruction is an exhibition that aims to answer this question, telling the story of two ancient Egyptian mummies through scientific imaging technologies.

Sanchita Balachandran, associate director of the Archaeological Museum, and Eastern Studies graduate student Meg Swaney, sat down for an interview with The News-Letter to speak about the project, which sits at the intersection of archaeology and scientific technology.

Taking on such a significant project required a large variety of scientific methods across many different fields. The researchers on the team began with computer tomography (CT) scanning at the Hopkins Hospital to extract skeletal information from the remains of the mummies. The team also used laser scanning to gain potential information about the skin but had to be especially mindful of the potential consequences of declaring the exact skin tones and textures with confidence. Additionally, in order to increase accuracy, the team looked to relevant sets of data on specific physical characteristics of the modern population to analyze the features of the two individuals.

Swaney emphasized that the team carefully considered the boundary between objectivity and subjectivity in their research.

“We tried to be transparent about what we can say with 100-percent accuracy and what is in the realm of subjectivity,” she said.

With all of the technological information, they then sent the data to Liverpool, England, where forensic anthropologist Caroline Wilkinson and her team created three-dimensional skull models of the two ancient individuals using the data in a virtual sculpture system called Geomagic Freeform.

In addition to examining the actual remains, the team used multiband imaging to look at the coffin associated with the Cohen Mummy to better understand the potential time period and cultural context for the individual and her mummification process.

Using these scientific technologies, the team sought to not only create a physical biography of these two ancient women but also to deepen our own contemporary understanding of and connection to these ancient lives.

According to Balachandran, one of the most challenging aspects of studying humans of the past through scientific methods is to treat these individuals as real human beings with unique lives and identities rather than as mere artifacts or objects to examine.

“It’s just about human dignity,” Balachandran said. “The technology is one way for us to get closer to that recognition that these are real people. We have to investigate them in certain ways, and we also have the responsibility to present the technological information in a way that really centers their humanness.”

According to Swaney, there can be a tendency among museum visitors to question the authenticity of displays of ancient humans and their remains.

This surprises Swaney because such thinking indicates that the visitor considers the ancient human simply as a standard collected object. But Swany believes that this is not the case.

“It becomes apparent that this is an authentic dead body, and then the corollary to this is that this was a once-living person with a unique biography,” she said. “It is essential that museums give visitors the tools to contextualize that person and to approach them as a person and make that connection.”

Swaney believes that it is not simply researchers who embark on a scientific and archaeological project that can establish a personal connection to people from the past.

Another important albeit challenging aspect of the scientific process itself was communicating and negotiating with experts in different specialties across various fields.

From her involvement in the interdisciplinary research effort, Swaney noted that having the right vocabulary to ask the right questions about these mummies was the key for researchers to steer the scientific process in the right direction.

Establishing the right kind of language made it possible to reduce personal bias and expectations. This was crucial when the researchers made more nuanced decisions such as about visual details like skin color or texture and gendered features.

Since the museum works so closely with cutting-edge technologies, it is also important to address what exactly our understanding of “science” is.

Balachandran noted that some people assume that we’ve only started using technological processes in our modern world. Contrary to such assumptions, however, the ancient Egyptians used all sorts of complex technologies such as the process of mummification and burials.

“Current technology that we embrace is a way that we as contemporary people make sense of things,” she added. “Technology has always existed, scientific tools have always existed. These are just the ones that we’re familiar with.”

Swaney elaborated further by noting that technology should be considered simply as a point of entry in making the information accessible rather than as an entirely separate field of analysis.

“Technology can be thought of as a contemporary language for conveying this [archaeological] information,” she said.

For Swaney, the goal of utilizing science and technology in the museum is not to create a “monument to technology” but rather to equip individuals from varying backgrounds and levels of scientific or archaeological knowledge with the tools to build personal connections to potentially far-away people and cultures.

“I say goodnight to her when I turn the lights off,” Balachandran said of the mummified individual. “When you’ve spent this much time thinking about somebody, it’s really important for you to maintain that relationship. I would really hope that [connection to the individuals of the past] is something that would be part of the social life of a Hopkins undergraduate.”

Hopkins students interested in pursuing these fields can take courses on ancient technology taught by Balachandran or other courses that work with museum collections. Additionally, interested students can always visit the museum itself.

Meanwhile, the Hopkins Archaeological Museum will continue to explore humanity through the intersection of archaeology, science and technology.