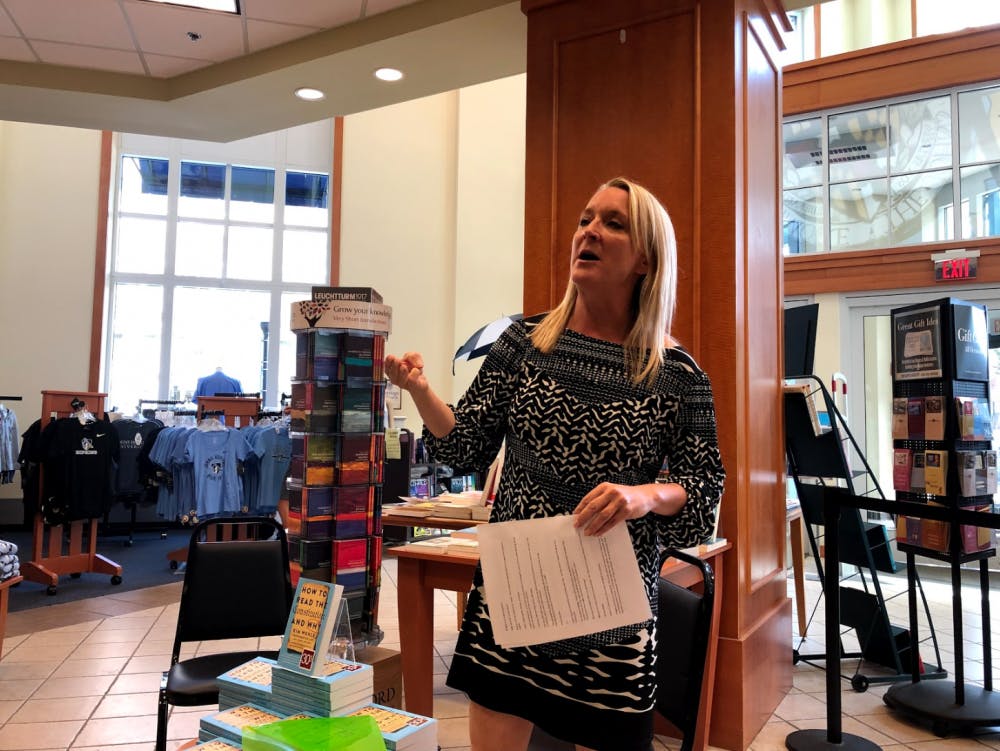

University of Baltimore law professor Kimberly Wehle presented her latest book, How to Read the Constitution — and Why, at the Hopkins Barnes & Noble last Sunday. In her discussion, Wehle insisted that the challenges the American constitutional order is facing right now are serious, but not necessarily insurmountable.

“I’m a little bereft like everybody else,” she said. “I share this sentiment of asking, ‘What are we going to do?’ But it’s not an option to just slip into autocracy and tyranny. That’s not acceptable to me. So we do what we can do, which is numbers and numbers and numbers of people going to the polls and voting for themselves, their families and their communities.”

Wehle’s talk centered on a discussion of constitutional rights. Many Americans, she said, know what some of these rights may be, or at least they think they do, but far fewer would be able to explain what a right is.

“It’s not like sort of the unicorn floating above us swooping in to protect us when we need it,“ Wehle said. “The constitutional right means you can go to court and get a court order to tell the government to stop doing something, stop barricading your house or even get money from the government for hurting you.”

The U.S. Constitution, Wehle explained, outlines the rights, or claims against the government, that Americans are due. She compared this function to that of a job description. In the workplace, a manager cannot expect an employee to do something not prescribed by their job description. If the dispute goes any further, all the employee has to do is point to the terms of their job description.

The same principle holds with the Constitution. If the government attempts to exceed its constitutional powers, that can be remedied by bringing it before the courts and pointing to the Constitution. However, Wehle conceded, it is hardly ever quite so simple.

“The Constitution and our rights — those are the abilities to limit government, to hold government accountable, to be able to rule ourselves — is not God-given nor self-enforcing.”

Wehle argued that one has to make a convincing argument that one’s rights are being violated in order to have the legal system step in and take action. An analogous situation could be when one party to a contract complains that the other has just taken her money and walked away with it. An unenforced contract has no more force than just a blank sheet of paper.

The threat of consequences is what actually gives effect to contracts and the Constitution alike, Wehle asserted. Just as how drivers who speed will slow down when they see traffic cameras, public officials will be slower to abuse the powers of their office when they see that the citizenry will not abide their doing so.

“Always look where’s the red light: there’s a red light somewhere,” Wehle said. “But if the red light is not enforced, there is no red light. And that power becomes absolute. It’s up to us to limit it.”

Wehle argued that the system designed by the Framers of the Constitution has functioned well, at least up until the present day. In today’s world, politicians no longer seem to believe that there may be consequences for their actions, explaining much of U.S. President Donald Trump’s behavior, Wehle said.

“When we ask, ‘Can he do that?’ the question is then, ‘What are the consequences?’ If there are no consequences, the answer is yes.”

Wehle reflected on why she feels Americans may not be as bent as they could be on guarding their constitutional rights.

First, the text of the Constitution is roughly 230 years old. This alone would account for some degree of difficulty in parsing it. Then add onto that the fact that the language overall displays an appreciation for brevity. Interpretation then becomes even more difficult relative to a standard modern text.

This is why, Wehle said, professors like her can and do teach entire courses devoted to constitutional interpretation. There is no substitute for getting in and reading and struggling with constitutional language, she maintained.

“It’s a bit like riding a bike... You can tell children how to ride a bike for 13 weeks of a semester and until they get on and struggle with it a little bit and wobble around, they are going to fall. You have to get on the constitutional bike to ride it,” she said.

Wehle emphasized the importance of getting students to realize that no school of constitutional interpretation can or should reign supreme.

“Justice Gorsuch and others convey this idea that there is one way of reading the Constitution: there is not... He might rely more on texts from 1787, and that is fine, but the suggestion that there’s one way to read it is false. Law, like life, is gray.”

The mention of Justice Gorsuch is not accidental. Although Wehle disagrees with his judicial philosophy, she recognizes that as a leader of the ascendant right wing of the Supreme Court, he holds enormous sway in the constitutional order.

For the people to amend the Constitution, they must sway two-thirds of the Congress and three-quarters of the states. This requires a truly overwhelming democratic consensus, which helps to explain why it has happened so infrequently throughout American history.

By contrast, Justice Gorsuch can effectively amend the Constitution by swaying just four of his fellow justices to sign onto his opinion. This happens far more frequently.

What all of this dysfunction in the operation of the constitutional order amounts to, Wehle said, merits serious concern.

“My honest fear, and I’m not the only one — other constitutional scholars agree — is that we could see democracy fail in our lifetime in this country.”

Wehle concluded with the takeaways that she’s gleaned from her many years of teaching and writing in this area. What they amounted to was: beware the power only grows unless it is checked; normal people must always be willing to stand up to creeping tyranny; and the common interest must come before all else.

After the talk, two audience members — Brian Watson and Ryan Deller — told The News-Letter that they both thought it was a good sign that such discussions were happening and were encouraged by the presentation.

Deller, a local high school teacher, said that while he was reading the book, he was pleased to find that it closely followed his curriculum for teaching civics and American history to his students. He believes that the questions Wehle raised in her book and in her talk are questions that he thinks Americans should be constantly grappling with.

Watson was a graduate of the last class to come out of Eastern High School.

“I think the talk was very healthy,” Watson said. “The environment was definitely very appropriate. The timing was good. The whole set-up I thought was very well organized and I learned a lot from it.”