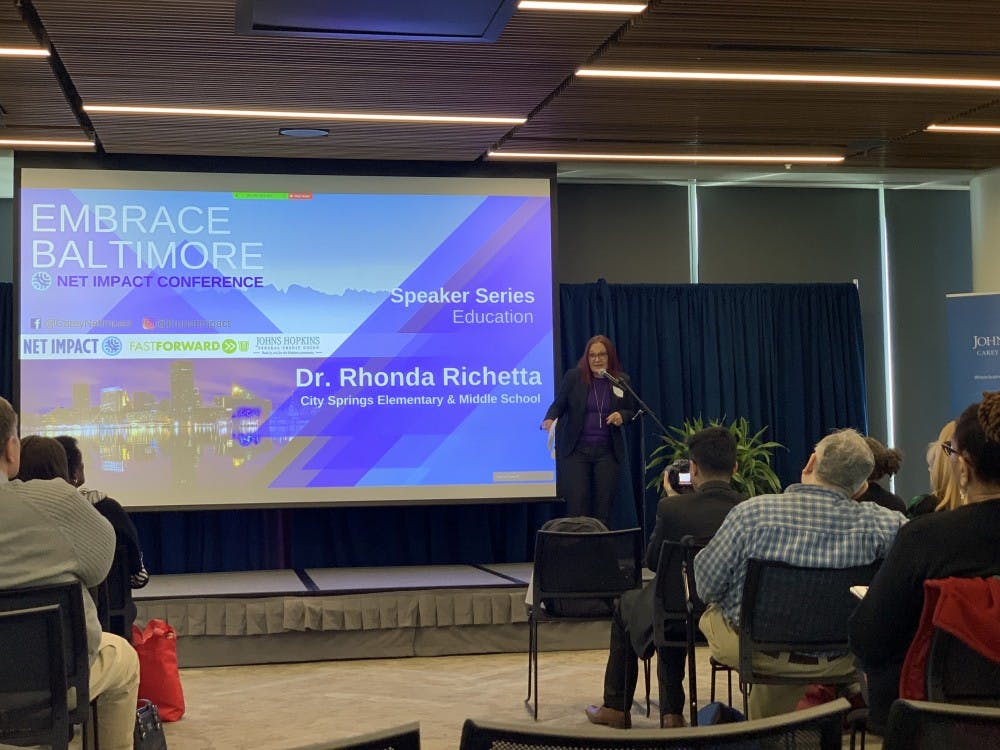

Baltimore entrepreneurs and social innovators came to the Carey Business School on Saturday to present their work to students and community members at the 2019 Net Impact Conference: Embrace Baltimore. Speakers included Elizabeth Nix, an associate professor in the division of Legal, Ethical and Historical Studies at the University of Baltimore, and Rhonda Richetta, a principal at City Springs Elementary/Middle School. The Carey Net Impact chapter hosted the conference.

Nix spoke about the historical and geographic influences that played a role in shaping Baltimore, including its easily accessible port, which helped turn the location into an economic powerhouse.

“All the developed areas were right around the harbor because people wanted to walk to work and that’s where the jobs were. There were warehouses, people were moving things in and out, there was ship-building, there was ship-repairing, all of those industries depended on being near the water. Baltimore’s location here on the water and leading into the hinterlands made it perfect as a transportation hub,” she said.

At the time, Baltimore surpassed even other coastal cities in terms of technology and economy. Nix explained that Baltimore had the first railroad in the U.S. and constructed some of the fastest ships on the market at the time.

An integral part of that booming economy, according to Nix, was free African Americans.

“A lot of people don’t know that... but we had the largest population of free African Americans before the Civil War,” Nix said. “Twenty-five thousand, five hundred people. Twelve percent of the city was free people of color.”

Because Maryland was a slave state, emancipated African Americans would often move to the city to earn money to free their friends and relatives.

“The capital that the community is amassing is often going back into the slave system. So just think about the injustice of that. They’re having to buy their friends and relatives out of slavery, and that money is going to enslavers,” Nix said.

In addition, public schools were not open to the children of taxpaying black residents.

“In Baltimore City, there were public schools, but they were only open to white people before the Civil War. So the black church took over a lot of the responsibility covering education — not just religious education but all kinds of education,” Nix said.

The other speakers focused primarily on their own initiatives in the city, all of which aim to address socioeconomic and racial inequity in Baltimore.

Richetta discussed her experience as a principal at a school in a predominantly low-income neighborhood. She told several anecdotes about her experiences confronting social and educational issues, using Jamal as a pseudonym for one of her students.

“A situation that happened one day after school, Jamal was picked up at dismissal time by his grandfather and his teacher allowed him to go with this man whom she thought was his grandfather — until his mother showed up a little while later saying, ‘Where’s my son?’, and when the teacher said, ‘He left with his grandfather,’ she said, ‘What grandfather? He doesn’t have a grandfather,’” she said.

Richetta concluded that two kids had been switched at pick-up and that Jamal was taken home by another student’s grandfather. It took that family several hours to notice the mistake. Richetta then explained the challenges tied to working with children primarily from lower-class backgrounds, pointing out that very few stereotypical middle-class parents would ever pick up the wrong kid, let alone not notice for an entire evening.

“What happened that day was that three hours passed and no one had a conversation with that child, no conversation about ‘How was your day?’; the child walked in the house, the grandmother said ‘Take off your coat, and go sit in front of the TV,’ and that’s what he did,” she said.

Richetta tied this story to the broader issue of educational inequity.

“When my ‘children’ come to school on their very first day, they walk in the door and they’re already behind. They have very low vocabulary, their language skills are low, they have very little background knowledge, because the other thing that would happen in a middle-class family is in the evening, they would sit around a table and they would have dinner-time conversation, and throughout that conversation, Jamal would learn a lot. He would learn new vocabulary words, he would learn a lot of things about the world that he didn’t know, and that doesn’t happen with the children that attend my school at the end of the day,” she said.

Drawing on this anecdote, Richetta argued that these issues have been prevalent, both locally and nationally, for generations.

“What I have learned is that racial disparity really does exist. It exists today in this country, it exists in Baltimore; in fact, the disparity between blacks and whites, that education gap, is exactly the same as it was in 1990. I tell my teachers all the time that what we need to be is equity warriors because the other thing that I’ve learned is that ‘equal’ is not fair,” Richetta said.

Martin Schwartz, another speaker at the conference, founded Vehicles for Change in 1999. His organization receives car donations from the public, repairs the cars and then sells them at deep markdowns to eligible families, referred to his organization by social service agencies. Since its start, the initiative has awarded over 6,000 cars, resulting in 75 percent of recipients claiming to have received better jobs or pay increases since the donation.

“Transportation was identified as the number one barrier for low-income families to gain and maintain employment over any other barrier in the country. Think about that. If you don’t have a car and you live in Sandtown or Cherry Hill, you, your children and your children’s children are never going to ever escape Baltimore,” Schwartz said. “That is a scary thought. We can go down today and we can get everyone in Cherry Hill a PhD, and they will be in poverty for the rest of their lives and their children will be in poverty because they can’t get to a job.”

Other conference speakers included: Lawrence Grandpre, the director of research at racial equity grassroots movement Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle; Anna Fitzgibbon, the founder of Outgrowth LLC, a student-farm outreach organization; and Pamela Kellett, who played a large role in designing and implementing the Baltimore Trash Wheels, floating solar-powered trash-collecting machines that have picked up over 800 tons of trash from Inner Harbor since 2014.

Following the speakers’ presentations, conference attendees attended a fireside chat with Bishop Douglas Miles, a Hopkins alum and founder of the Black Student Union who has dedicated his life to fighting for social justice in Baltimore. The conference concluded with workshops on financial literacy, social entrepreneurship, impact investing and a food solutions challenge.