Teaching for Change’s Alison Kysia led a discussion titled “The Story of Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf” on Monday. Teaching for Change is a D.C. nonprofit organization promoting social justice initiatives through educational outreach in schools. The event featured a partial screening of By the Dawn’s Early Light: Chris Jackson’s Journey to Islam, followed by an interactive conversation about black and Islamic representation in media. The Johns Hopkins University Muslim Association (JHUMA), the Office of Multicultural Affairs and the Department of Islamic Studies co-hosted the event.

By the Dawn’s Early Light, directed by Zareena Grewal, tells the story of Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, a former professional basketball player. In 1996, a few years into his National Basketball Association (NBA) career, he began refusing to stand for the national anthem at games. His refusal ignited a media firestorm, including mixed reactions from both black and Muslim athletes and individuals.

Zoya Sattar, president of JHUMA, explained in an email to The News-Letter why JHUMA decided to co-host the event.

“JHUMA was informed of Ms. Kysia’s work through Professor Homayra Ziad at the Islamic Studies Department,” she wrote. “Her and Ms. Kysia have worked together in the past, and Professor Ziad thought it would be a great idea to have her come on to campus.”

Kysia is the project director of the Teaching for Change’s program Islamophobia: A People’s History Teaching Guide, which includes lesson plans and video clips to educate students accurately on Muslim history in the U.S. Kysia used a lesson plan titled “Black Athlete Protest: The Case of Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf” to guide Monday’s discussion.

By the Dawn’s Early Light explores Abdul-Rauf’s childhood, his rise to fame and the controversy surrounding his later career. Born Chris Jackson in 1969, Abdul-Rauf was raised by a single mother in a lower-class neighborhood in Gulfport, Miss. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was active in the area, which was a cause of concern for black residents such as Abdul-Rauf.

Abdul-Rauf also suffered from Tourette Syndrome from a young age but was undiagnosed until high school. As he grew up, he devoted all of his time to basketball.

“Basketball, it became that father figure that I never had,” he said in the documentary.

Abdul-Rauf began playing for Louisiana State University and was drafted to the NBA’s Denver Nuggets in 1990. A year later, he converted to Islam; three years later, he legally changed his name. Throughout the documentary, filmmakers portrayed Abdul-Rauf as constantly searching for something. He explained that after reading Malcolm X in college, he started becoming more attuned to Islam.

“I found myself becoming more globally aware and concerned and active,” he said in the film.

In 1996, Abdul-Rauf chose not to stand when the national anthem was played before games. He believed that the American flag was a symbol of oppression.

“What caused me not to stand was just my Muslim conscience,” he said in the documentary.

Abdul-Rauf’s refusal to stand during the national anthem led to his temporary suspension from the NBA and a strong media reaction to his decision. By the Dawn’s Early Light featured reactions to the controversy from various people, including Abdul-Rauf, Muslim immigrants to the U.S. and other NBA players.

Kysia frequently paused the video to ask questions to the audience. She asked the viewers what they thought of the different reactions to Abdul-Rauf’s choice not to stand.

Abdul-Rauf’s suspension took place in 1996 and By the Dawn’s Early Light debuted in 2004, but Kysia put Abdul-Rauf’s decision in a modern context. She urged the audience to think about the similarities between Abdul-Rauf’s case and that of Colin Kaepernick, a black NFL player who was the target of both widespread support and fury for kneeling during the national anthem to protest anti-black police brutality.

“It’s not much different in that respect,” Kysia said.

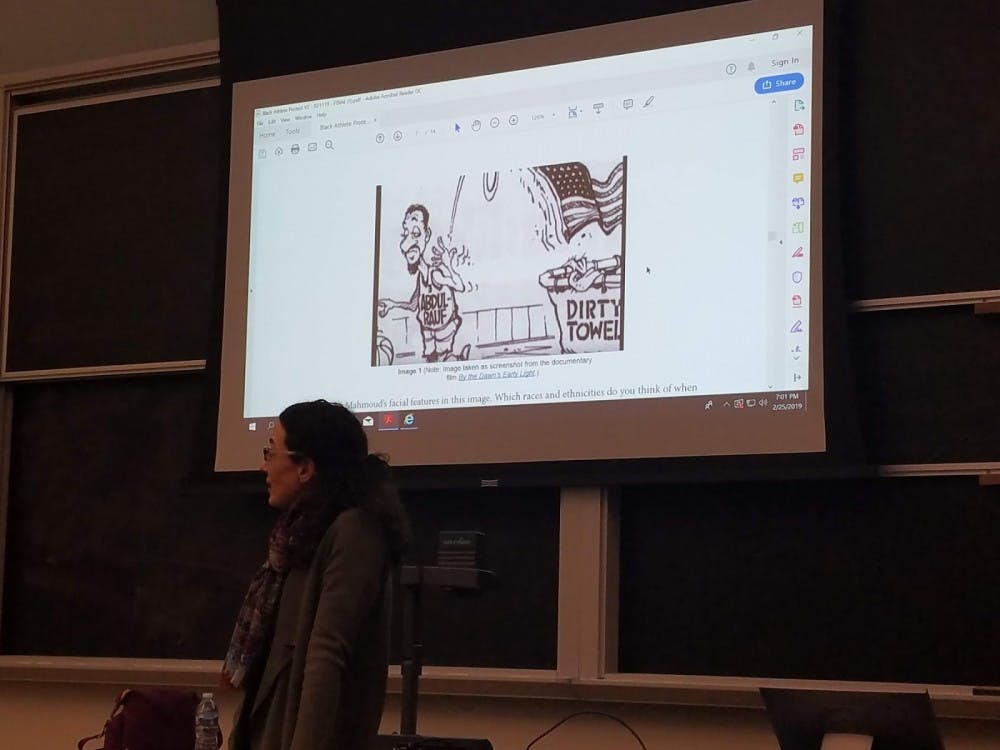

Kysia distinguished between the media’s two main reactions to Abdul-Rauf. One was to paint him as a clueless, while the other was to negatively play on his Muslim and black identity. Kysia focused more on the latter portrayal. One newspaper cartoon showed Abdul-Rauf throwing the American flag into a basket of dirty towels. People in the audience pointed out that the cartoon showed Abdul-Rauf with a large hooked nose and a more prominent beard than the one he had in reality.

Kysia explained that the cartoon plays on anti-Muslim, anti-Semitic and anti-black stereotypes.

“It’s leaving us in this ambiguous space,” she said. “‘We don’t know where this guy’s from, but he’s not from here.’ Even though he is from here!”

She further noted the Muslim community’s seeming lack of support for Abdul-Rauf at the time. Most immigrant Muslim leaders quoted in the documentary did not support his decision and distanced themselves from Abdul-Rauf.

Kysia discussed the prevalence of anti-black sentiment in immigrant Muslim communities.

“It’s not just a Muslim/non-Muslim conversation,” she said. “Everyone in the U.S. lives in a deeply racist culture.”

In an email to The News-Letter, Sattar wrote that Abdul-Rauf’s story has modern-day implications.

“His story shows that racism is alive and well in the Muslim community, as well as the devastating effects of this racism culminating in a lack of support,” she wrote.

Kysia believes that, generally, people are ignorant about races other than their own. She also thinks that schools in America are not sufficiently racially diverse.

“This whole notion of desegregation never really happened,” she said. “And this increases racism, as exposure to other races is the best way to sympathize with others’ experiences. If you actually know somebody from a group of people, you’re far less likely to be prejudiced against them... We can find the answer through education.”

Sattar also hoped that the event would help educate people.

“JHUMA’s target audience was the student Muslim population as anti-blackness and unfamiliarity with the history of Islam in black communities is prevalent in our immigrant communities,” Sattar wrote.

Kysia feels that American textbooks and political policy continue to contribute to anti-Muslim and anti-black sentiment. However, she believes this can change in the future. She pointed to the changing narrative surrounding gay marriage as an example.

She feels that both Islamophobia and racism can be combated by lessons such as those provided by Teaching For Change. She believes the best way to fight both is through the increased visibility of different groups of people.

“We are all infected by this,” she said. “And we all have to be studying what racism is and how it affects different people in different ways.”