When was the last time you paid attention to the art in the library? The last time I did, perhaps one of the only few times, was when it was pointed out to me by an enraged security guard. This was a piece called Runaways by Glenn Ligon.

I work at the Service Desk in the Milton S. Eisenhower Library (MSE), and on one of my late shifts a few weeks ago, I noticed a security guard speaking to another quite animatedly.

“I’m never setting foot in this building again!” she exclaimed.

I timidly asked her if I could help her with whatever was troubling her. Her reply was emotionally charged. She told me that of all the artworks on M-level, the one exhibit that displayed African-American people and culture was a set of advertisements for runaway slaves.

“Of all the things you could display about black life, you choose to show black people as slaves,” she said. “You could’ve just put up a picture of MLK [Martin Luther King Jr.], and I would have been happy.”

I understood her anger; she felt as if her identity had been reduced to the suffering of her ancestors, that the vast culture and art that black people have contributed to American society were ignored in favor of making a spectacle of a dark history.

Shocked by this revelation, I asked her if she could show me this piece, and she led me to it. I expected the art to be displayed in a small corner of the library. As it turns out, it sits in the most popular spot on M-level, opposite the glass display on the wall next to the desks. And yet it went unnoticed until a few heads turned as the guard pointed at them. I myself had sat around here multiple times and never noticed it until today.

“There is so much we have done,” she told me. “Every day we fight to move forward, and every day we’re reminded of our past, that we’ll still be seen as slaves.”

There were angry tears in her eyes as she showed me the piece, and all I could feel was embarrassment and horror that the institution I identify with and have pride in could cause so much pain to an outsider looking in.

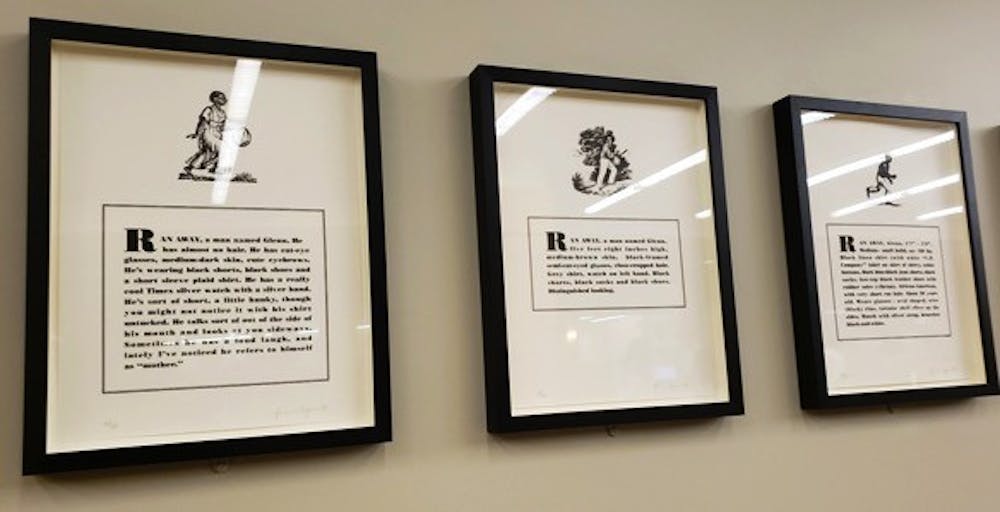

On closer examination, I found that Runaways, a series of 10 lithographs, is a satirical art piece by Glenn Ligon, an African-American artist famous for his conceptual art. The piece itself, as can be seen on a small plaque accompanying it, is a recreation of advertisements released in 19th century newspapers to locate runaway slaves, with Ligon being portrayed as the slave as drawn and described by his friends.

Ligon commented on his work in an interview conducted on July 11, 1997 by Thelma Golden.

“Runaways is broadly about how an individual’s identity is inextricable from the way one is positioned in the culture, from the ways people see you, from historical and political contexts.” I found this artwork to be an original and creative way of making a very powerful statement.

This realization made me want to discount my earlier experience with the work and hope that if the guard had known about the artist and looked more closely, she wouldn’t have felt as strongly offended by it. But I realized that it wasn’t the artwork itself she was opposed to, it was that the only representation of black culture in the library was of slavery and the reductive effect it has on the perception of African Americans. This led me to a deeper conversation about how context affects perception of art and the ethics of displaying art about collective suffering.

I reached out to Jackie O’ Regan, the curator of Cultural Properties at the Sheridan Libraries, to learn more about the story behind how the piece was chosen to be displayed in the library.

“Alumna and former trustee Constance R. Caplan gave Glenn Ligon’s ‘Runaways’ (1993) series to the university. She did visit campus and suggested the library because she (1) knew it’s where most Hopkins students congregate to study, do research, and socialize; (2) saw there was sufficient space — an important consideration since the work is a suite of ten framed lithographs; and (3) knew the library provides security,” she wrote in an email to The News-Letter.

O’Regan explained the importance of Ligon’s work.

“Ligon, who is African American, is one of the most important artists working in America today,” she wrote. “His work is known for being beautiful and provocative, and it’s important for the campus community to interact with challenging artwork, just as we tackle challenging subjects and ideas in the classroom.”

Ligon’s piece was meant to challenge, shock and simmer in your mind for days. This article is proof that it fulfilled this purpose. But would this have happened if the artwork hadn’t shocked the security guard first, or would I have only ever seen it out of the corners of my vision like most other students? I do believe that an astounding work of art like this deserves a wide audience, and a library on a college campus would seem like a natural winner, but does the audience deserve this work of art?

What makes us undeserving is our privilege and thus, our ignorance. Despite the optimistic rise in diversity in the past few decades and a steadily growing black community, Hopkins is still a historically white private institution, with a student body that is largely, if not racially then socioeconomically, privileged. Our distance from the issue gives us no reason to feel alarmed by it, unlike the immediate reaction of someone deeply tethered to its history.

Even if we noticed and spent time with it, what would it beget other than a few shaking heads and an intellectual consensus that “slavery was terrible”?

Is this moment of education and our distant sympathy enough to warrant the pain it causes? And after all these tireless years of progress and development, does the African-American population of this country not deserve to see representations of themselves beyond the image of the slave?

Runaways is a beautifully satirical piece of art, but it is placed in front of an audience that does not truly engage with it and in a context in which anyone who identifies with it finds themselves underrepresented.

Despite a lot of thinking, I cannot come up with a solution. It would simply be wrong to say that this piece should not be displayed; it is an African-American artist’s expression of criticism and anger and needs to be seen. Should the piece be moved to a place with a greater spotlight then? But if so, where else would one get more traffic than the library? Do we need to become a more engaged audience — more empathetic and aware, but if so, how?

I’ve raised a lot of questions that I simply cannot (and should not attempt to) answer myself. Though in some way, I hope to help Ligon challenge our thinking the way his work means to and begin the conversation it begs for.

The one conclusion I have arrived at though is that for every representation we have of black suffering, we need to have twice as many of black victory.

Because far more powerful than a spectacle of pity and pain are the emotions of inspiration and awe. Because to rise against the odds and the suffering and to create a culture as vibrant and influential as the African-American one is cause to celebrate.