Three days after Baltimore City celebrated Henrietta Lacks Day, the Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) held its eighth annual Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture Series on Saturday at the Turner Auditorium at the Hopkins East Baltimore campus.

Henrietta Lacks, who died in 1951, was an African-American patient with cervical cancer whose cells were taken by Johns Hopkins Hospital without her consent. Since then, her cells, known as HeLa cells, have contributed to many significant medical discoveries.

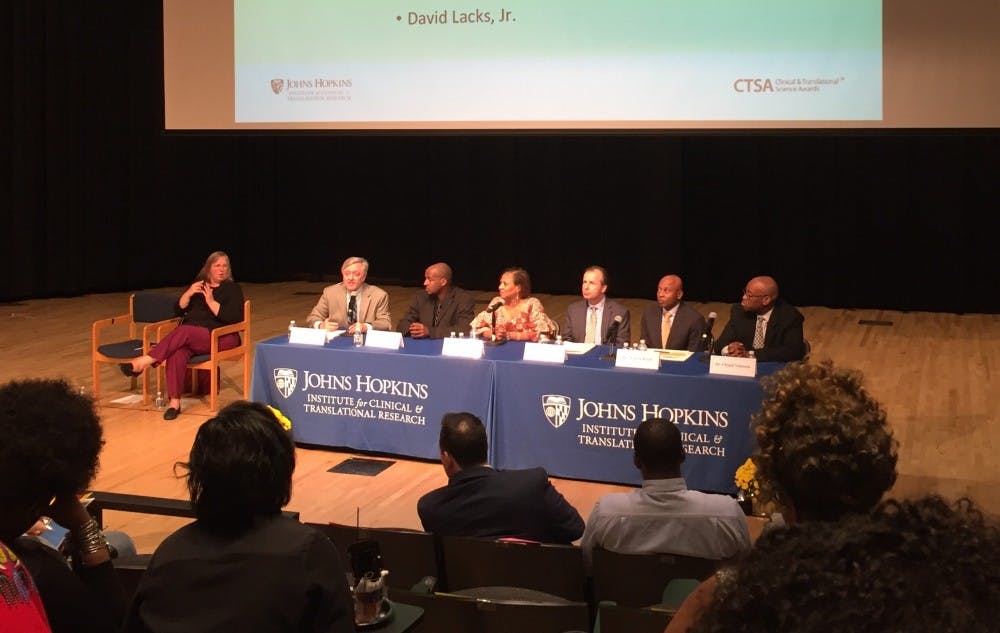

Three of her descendants participated in the lecture: Henrietta Lacks’ grandson David Lacks Jr. and two of her great-granddaughters, Aiyana Rodgers and Veronica Robinson.

Other speakers included Dr. Daniel Ford, ICTR director, and Dr. William Wade Jr., whose father had recommended Hopkins Hospital to Lacks and had served as her primary care physician.

Dr. Robert W. Blum, Director of the Hopkins Urban Health Institute (UHI), presented the UHI Henrietta Lacks Memorial Award to Turnaround Tuesday, a program developed by Baltimoreans United in Leadership Development (BUILD) to secure jobs for unemployed citizens.

Dr. Lisa Cooper, Bloomberg distinguished professor and director of the Hopkins Center for Health Equity, gave a keynote speech titled “Reaching Health Equity and Social Justice in Baltimore.” She described coming to Baltimore in the late ’80s and being struck by the City’s socioeconomic gaps.

“There were a lot of people struggling with poverty, not having opportunities to get an education, to get a good job,” she said. “There was stress going on in neighborhoods due to the drug epidemic and to crime.”

Social instability led to misunderstandings between doctors and patients — namely African-American patients, whom Cooper’s colleagues assumed were coming in for drugs.

“A lot of my colleagues who weren’t African-American would look at me, as if I could translate,” she said. “If you just listened to someone and tried to put yourself in their shoes, then you would hear what the struggle is.”

To highlight the severity of health disparities within Baltimore, she compared Madison-Eastend, a neighborhood in East Baltimore, to Roland Park, a predominantly white neighborhood whose mean income is three times higher. The two neighborhoods are about five miles apart, but there is a 20 year difference in life expectancy. Roland Park residents live 83 years on average, while Eastend residents live an average of 63 years.

After conducting surveys and interviews with patients from various racial and ethnic groups, Cooper discovered that there were lower levels of trust in physicians, hospitals and researchers among African-Americans and other minority groups.

She believes that this mistrust stems from a history of discrimination against minorities.

“[Ethnic minorities] were asked less often to participate in decisions about their care,” she said.

After analyzing exchanges between doctors and patients, she noticed that doctors had fewer personal conversations with African-American patients, focusing instead on technical conversations about the patient’s condition.

She added that communication breakdowns were more frequent during interactions between white physicians and African-American patients, compared to interactions between physicians and patients from a similar ethnic background.

“We know that this is a natural thing: When we are like someone, we feel more comfortable,” she said. “But we can’t allow things like that to influence the delivery of care when they’re sick.”

Calling for greater community effort in resolving health disparities, Cooper discussed the role of the Hopkins Center for Health Equity, which partners with communities and trains scholars, as well as raising awareness and promoting policy reform.

“Health equity is everyone’s problem,” she said.

Following Cooper’s speech, audience members were able to submit questions on notecards for a panel Q&A session moderated by Ford. Amongst the five panelists were Cooper and David Lacks Jr.

In response to a question on how DNA and sequencing data could be responsibly obtained, Lacks stressed the importance of consent and making sure everyone involved is properly informed.

“Being on the National Institute of Health (NIH) board, I can see what is going on,” he said. “You want to know what is going on, be more engaged and willing to help.”

Robinson, who serves as executive director of the Lacks family’s nonprofit organization Henrietta Lacks HeLa Legacy Foundation, reflected on her family’s role as advocates for health equity.

“We will break down these barriers between the community and the health care field to continue my great-grandmother’s legacy,” she said.

She stated that in continuing her great-grandmother’s legacy, the Lacks family made themselves responsible for promoting health equity.

“Our great-grandmother’s story can be your family’s story,” she said. “Sometimes bad things happen to good people so that great things can happen for others. That’s part of my great-grandmother’s story.”

Natasha Hemeng, a student in the Hopkins School of Nursing, attended the event to learn more about Lacks’ legacy.

“Hopkins was the main contributor of real injustices from the case of Henrietta Lacks,” she said. “I just wanted to see what steps towards progression or solutions or involvement that they have in the present day.”

While she appreciated the event as a way to honor Lacks’ legacy, she felt that the lecture series failed to fulfill its agenda.

“We’re not really addressing the ideas of health disparity and how situations that may not be as extreme [as the Lacks case] still happen today,” she said. “Especially here in Baltimore... the African-American population is still very much suffering.”

Jodie Pelusi, another student in the Hopkins School of Nursing, praised the lectures but felt that Hopkins had not properly made up for what happened to Henrietta Lacks.

“They didn’t address the wrongs that happened in the past,” she said. “We can’t really move forward without reflecting on the past.”