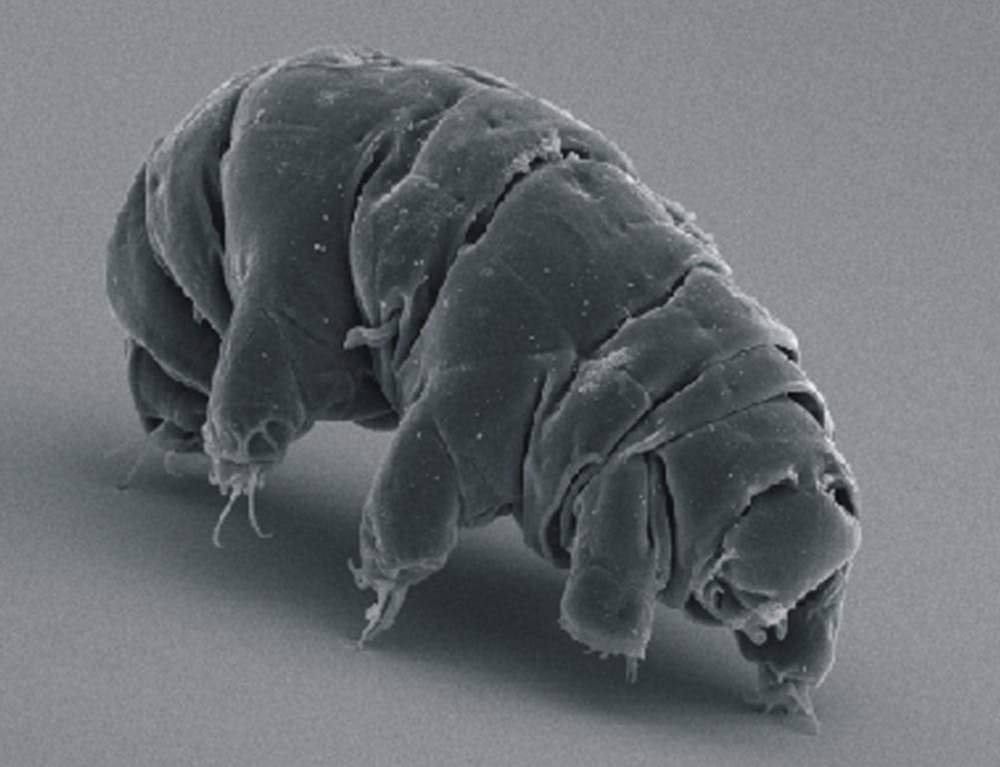

If you consider Siberian tigers or saltwater crocodiles to be the toughest animals on the planet, think again. Tardigrades, also known as “water bears,” are microscopic aquatic animals with four pairs of legs that average half a millimeter in length.

Among the more than 1,000 species of tardigrades, some can be found in leaf litter or between moss cushions, while others can be found in marine or freshwater environments.

According to an article published by Nature Communications on Sept. 20, a group of Japanese scientists led by Takumo Hashimoto at the University of Tokyo analyzed the genome of Ramazzottius varieornatus, an especially stress-tolerant tardigrade species, to determine the mechanism that allowed tardigrades to protect themselves in harsh environments.

Despite their chubby figure, tardigrades are capable of surviving in extreme conditions, including complete dehydration. During times of desiccation, a state of extreme dryness, tardigrades lose body water and shrink into a state called anhydrobiosis.

According to the authors of the paper, this almost invincible state allows tardigrades to withstand temperatures on extreme ends of the spectrum (from -273 degrees Celsius to nearly 100 degrees Celsius) as well as high pressure, immersion in different organic solvents, exposure to high dose irradiation and even direct exposure to space in low Earth orbit.

After the researchers decoded and sequenced the entire genome of R. varieornatus, they compared its genome to the genomes of other organisms and discovered that the tardigrade genome contains many more stress-related genes, superoxide dismutases (SODs) and MRE11, than other animals.

SODs help tardigrades endure dehydration by relieving oxidative stress. MER11 genes help repair damaged DNA that undergo DNA double-stand breaks (DSBs) during dehydration. Specifically, the tardigrade genome contains 16 SODs sequences and four MRE11 genes, whereas most animals have less than ten SODS sequences and only one MRE11.

Hashimoto and his team also discovered a special protein called Damage suppressor (Dsup) that is associated with the protection of DNA during their research.

The researchers infer that Dsup protein’s high basicity, particularly in the C-terminal region, is responsible for enclosing the DNA through electrostatic interactions. This envelopment then shields DNA from irradiation stress.

To prove the association of Dsup with DNA damage suppression, researchers genetically engineered the Dsup gene into human cells and exposed those cells to X-rays, which can induce DSB formation. In addition, X-rays can induce single-strand breaks (SSBs) through direct absorption of X-rays or reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Hashimoto’s results demonstrated that irradiated Dsup-expressing cells had only 16 percent of the DNA SSBs generated by direct absorption compared to the 33 percent for normal cells without Dsup expression.

Irradiated Dsup-expressing cells only had 18 percent of DNA SSBs generated by reactive oxygen species compared to the 71 percent for normal cells without Dsup expression. Dsup proteins also reduced X-ray induced DSBs by 40 percent. These findings both indicate that the expression of Dsup can protect DNA from radiation and opens up possibilities in various fields.

Ingemar Jönsson, an evolutionary ecologist who studies tardigrades at Kristianstad University in Sweden, said in an article published in Nature that the “protection and repair of DNA is a fundamental component of all cells and a central aspect in many human diseases, including cancer.”

The discovery of the Dsup protein is only the beginning of what the tardigrade genome offers. The researchers believe that, using their R. varieornatus genome sequence, more genes like Dsup may be found in future studies to enhance or impair a cell’s resilience to stress.