Where there’s a will, there’s a way. For extremophiles, those words aren’t just a mantra but a way of life. Thriving in environments from volcanoes to the frozen Arctic, extremophiles have found a way to adapt to the harshest environments on Earth. Research professor Jocelyne DiRuggiero and her team at Hopkins are studying these extremophiles to learn how they have come to be so versatile.

“Some questions I had at the beginning of my career that had to do with how microbial communities assemble and evolve in the environment are still the same,” DiRuggiero said.

Before coming to Hopkins, DiRuggiero worked at Claude Bernard University Lyon 1 in France and then at the University of Maryland. She has now been at Hopkins for about eight years.

“When I came to the U.S. I got interested in extreme environments. I just love volcanoes, so it was a perfect for me,” DiRuggiero said.

To study microorganisms in these extreme environments, DiRuggiero’s lab uses archaea as a model system.

Archaea is one of the three domains of life, along with bacteria and eukarya, which all life is descended from. DiRuggiero explained that these are the best extremophiles to work with because in extreme environments like high salt concentrations or high temperatures, it is more common to find archaea than bacteria.

Archaea also share a more recent common ancestor with eukarya, the domain that includes Homo sapiens. Humans and archaea have similar processes of DNA replication, a process that is fundamental to life.

DiRuggiero and her team focus on studying archaea that grow in rocks, striving to understand what forces drive their biodiversity and how archaea will respond to environmental stresses. They look at what processes or factors in individual archaea allow them to exist in such extreme environments. They also look at microbial communities to learn about their genetic diversity and what mechanisms sustain their ecosystem.

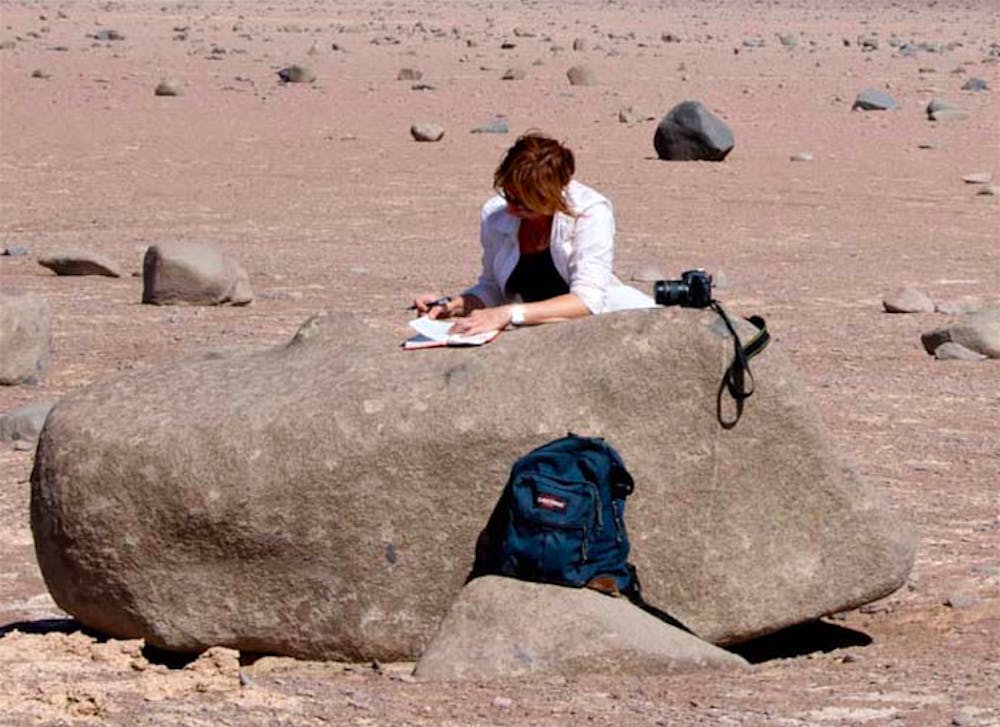

One focus in the lab is to understand how early life may have spread and evolved across Earth. In order to do so, DiRuggiero and her team must study rocks from deserts across the globe. This inspired them to create a citizen science project called Rockiology.

“We need to collect samples from all around the world, as many as we can. But I can’t go to every single desert around the world,” DiRuggiero said.

Citizen science is a general term for research that is conducted in part by amateur scientists. Rockiology asks amateur archaeologists to go into desserts, collect rocks that have been colonized by microbes and send them into DiRuggiero’s lab for analysis.

This way the team can study the differences in microbial extremophiles in different parts of the world. The study aims to answer whether all early life was initially dispersed over the entire Earth or if there were regional pockets that evolved separately at first.

Rockiology is a new program, but it has already reached far beyond Baltimore. DiRuggiero explained that someone in Arizona who homeschools children has contacted her and is now designing a curriculum based on Rockiology for the homeschooled students.

Beyond understanding the extremes of life on Earth, DiRuggiero’s work has implications much greater than our little planet; it can give insight into possible extraterrestrial life.

“If you look in the solar system — the closest place we can go — all these habitats where we think we might find life are very extreme,” DiRuggiero said. “If you understand what are the extremes of life on Earth, then you can think, ‘Where are the places where I can find life?’”

DiRuggiero also explained that by studying the microorganism communities found in rocks on Earth, we can narrow down locations where evidence of life might be found on Mars.

She went on to say that being able to teach and mentor graduate students makes her work that much more rewarding.

“Recently my graduate student submitted his first paper, and it was really big for him, and I was really happy. Those are the moments that you really feel proud about the students that you train,” she said.

When asked about her research, DiRuggiero said she also takes pride in the papers she has published.

Until the next one is published, DiRuggiero’s lab continues to study extremophiles and how they adapt to the most extreme environments on Earth.