A federal judge is allowing a $1 billion lawsuit against Hopkins to move forward after it was dismissed in 2016 for the University’s alleged involvement in a 1940s experiment that infected hundreds of Guatemalans with sexually transmitted diseases.

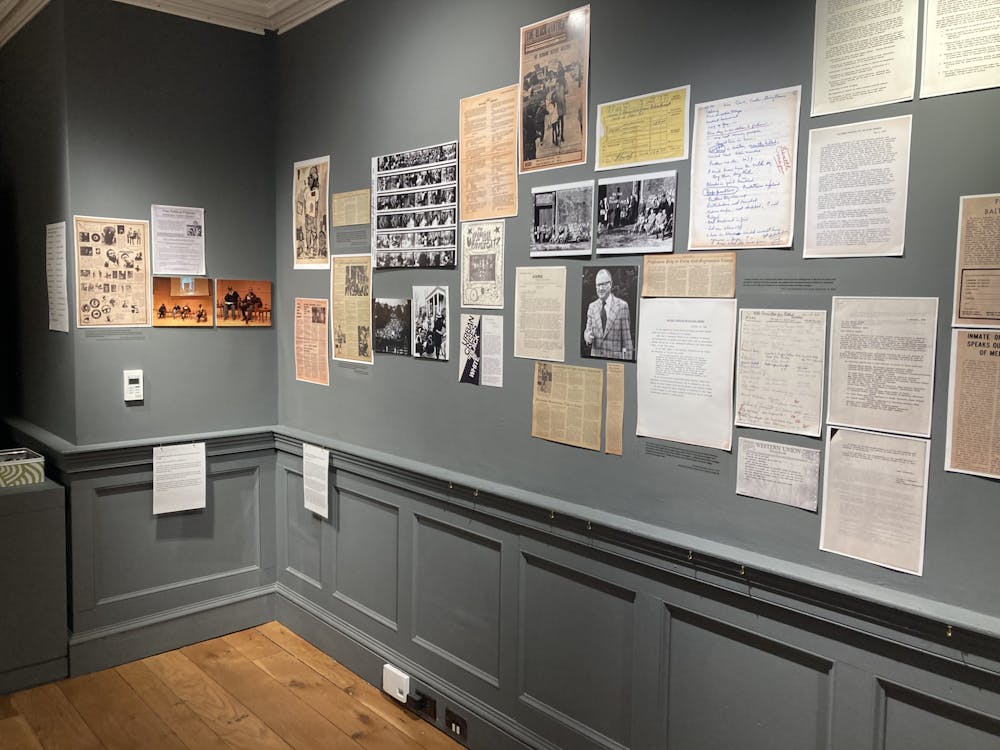

In the 1940s, the U.S. government conducted studies in Guatemala by intentionally infecting people with diseases like syphilis and gonorrhea without their consent. Subjects included psychiatric patients, soldiers, prisoners and sex workers. Several Hopkins physicians and doctors held positions on a committee that reviewed the research proposal in Guatemala.

Kim Hoppe, director of public relations and corporate communications for Johns Hopkins Medicine, defended the University.

“We feel profound sympathy for the individuals and families impacted, and reiterate that this 1940’s study in Guatemala was funded and conducted by the U.S. government, not by Hopkins. We will continue to vigorously defend the lawsuit,” she wrote in an email to The News-Letter.

Hoppe also clarified that the lawsuit was not reopened. Instead, the federal judge dismissed the plaintiffs’ claims for damages under the Guatemalan civil code but allowed claims made by direct victims and their family members.

“We are pleased that the judge dismissed a significant portion of the complaint and maintain that the plaintiffs’ claims are not supported by the facts or the law,” Hoppe wrote.

There are 842 plaintiffs, which include those directly affected by the experiment and their family members. In 2015 they filed a lawsuit naming Hopkins, the pharmaceutical company Bristol-Myers Squibb and a philanthropic organization called the Rockefeller Foundation as defendants. The plaintiffs are seeking up to $1 billion in punitive damages.

The experiments were kept secret for almost 60 years. In 2010, former U.S. President Barack Obama formally apologized to Guatemalan President Álvaro Colom. And in 2011, the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues, a panel of scientists and researchers meant to advise the President on bioethical subjects, released a report entitled “‘Ethically Impossible’ STD Research in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948.”

Research practices have changed since the Guatemala experiment. The University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), an independent ethics committee, puts forth several requirements for experiments today that involve human subjects. Researchers must ensure that the rights and wellbeing of research subjects are protected, the benefits of the research outweigh the risks, the “selection of subjects is equitable” and that the subjects give informed consent to the experiment.

Zaya Amgaabaatar, a senior majoring in public health and philosophy, learned about the Guatemala experiments because of her interest in bioethics. She explained that over the years, the scientific community has started to monitor the ethics of experiments.

“This was before IRBs. There was no large body governing what should be okay,” she said.

Amgaabaatar first learned more about the University’s alleged involvement in the Guatemala experiment in 2015, when plaintiffs first filed the lawsuit.

She views the Guatemala experiment as a case study in unethical experimentation, an example of all the practices that scientists today should avoid. Amgaabaatar also drew a comparison between the Guatemala studies and the Tuskegee syphilis experiments.

“A lot of people compare it to Tuskegee, which I think is interesting,” she said. “A big misconception in Tuskegee is that the U.S. Public Health Service was injecting African-American males with syphilis, which wasn’t the case. But they share similarities in that lots of violations of research ethics happened in both experiments.”

She also questioned the moral obligations of researchers.

“There’s a reason why it didn’t happen in the U.S.,” she said. “They wanted to use sex workers and vulnerable populations — they chose to do it in Guatemala. Should U.S. researchers be allowed to do things in a different country when the intended benefits of that research is still U.S. citizens?”

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The News-Letter.