Biologists at the Longevity Institute of the University of Southern California (USC) Leonard Davis School of Gerontology recently discovered a new diet that reduces the risk of age-related diseases.

47 million Americans suffer from metabolic syndrome, another name for five conditions that raise your risk for heart disease, diabetes and stroke. The five conditions are abdominal obesity (a large apple-shaped waistline), a high triglyceride level, high blood pressure, low levels of HDL cholesterol and high fasting blood sugar.

The National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute predicts that metabolic syndrome may replace smoking as the future leading risk for heart disease. Many adults attempt to mitigate the effects of metabolic syndrome by consuming no food and only drinking water for days at a time.

Although they may lose weight using this method, fasting leads to lower levels of circulating glucose, causing the body to start producing insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), which has been linked to cancer.

The scientists developed a low calorie fast-mimicking diet (FMD) that provided enough calories and nutrients to subjects to avoid producing IGF-1 while still suppressing the effects of metabolic syndrome. In a previous study the group showed that the diet was safe and feasible to consume for five days each month over a three-month period.

In the most recent study 100 subjects took part in a randomized trial. 71 participants ate the newly designed FMD for a five-day period each month for three months. 39 of the participants began eating the FMD and the team added 32 of the participants after they had eaten a control diet. The team then evaluated the effects of the FMD on risk factors and markers for aging, cancer and metabolic syndrome in healthy subjects who ranged between 20 and 70 years old.

Between April 2013 and July 2015 all 100 participants were assigned to two groups. 48 participants were in arm one and 52 were in arm two. The participants in control arm one continued their normal diet for three months, whereas participants in arm two started the FMD intervention.

While eating the FMD, the participants most commonly complained of fatigue, weakness and headaches. After three cycles of the FMD, the participants reported only mild or very moderate side effects.

Overall the team found that the subjects on the FMD lost an average of about six pounds. Their waistlines shrank by one to two inches and their systolic blood pressure, which was in the normal range when the study began, dropped by 4.5 mmHG, while their diastolic blood pressure dropped by 3.1 mmHg. Their levels of IGF-1 also dropped significantly, reaching a range associated with lower cancer risk.

“After the first group completed their three months on the fasting diet, we moved over participants in the control group to see if they also would experience similar results,” Valter Longo, director of the USC Longevity Institute and a professor of biological sciences at USC Dana and David Dornsife College, said.

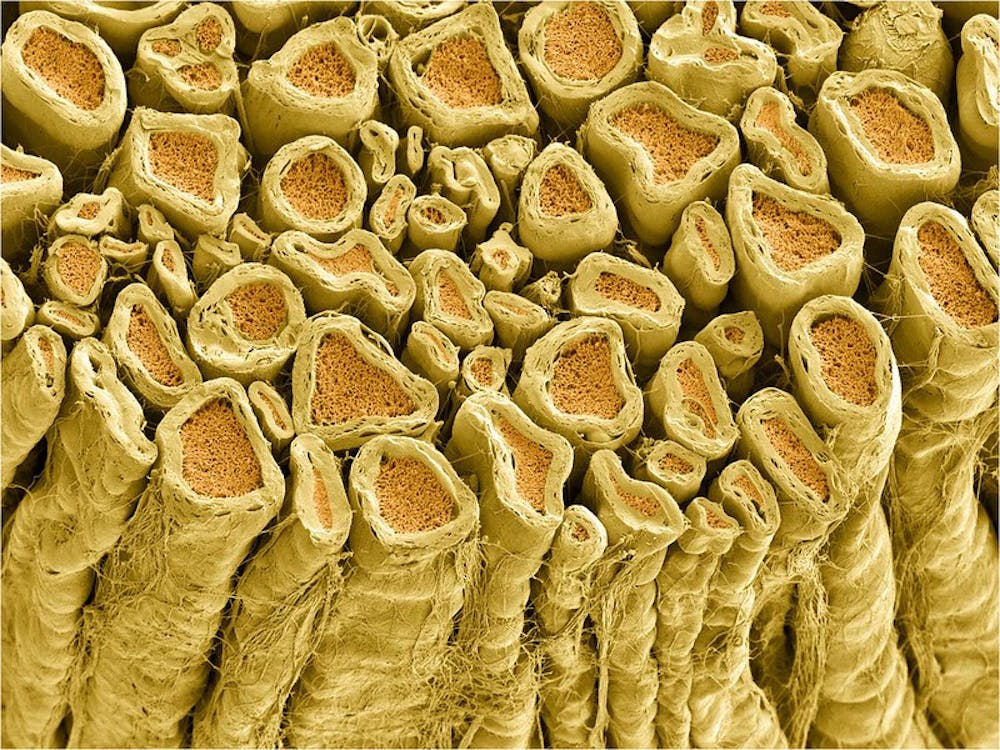

“We saw similar outcomes, which provides further evidence that a fasting-mimicking diet has effects on many metabolic and disease markers. Our mouse studies using a similar fasting-mimicking diet indicate that these beneficial effects are caused by multi-system regeneration and rejuvenation in the body at the cellular and organ levels,” Longo said.

He added that the subjects retained the benefits after the trial period.

“Our participants retained those effects, even when they returned to their normal daily eating habits,” he said.

The team noticed that subjects who were considered “at risk” at the beginning of the trial, because they had one of the five conditions, made large improvements to healthier living over the course of the trial.

“Fasting seems to be the most beneficial for patients who have the great risk factors for disease, such as those who have high blood pressure or pre-diabetes or who are obese,” Longo said.

Three months after the trial ended, the researchers invited the participants back and found that they continued to benefit from the diet even after they stopped eating it. To confirm the effects of the FMD on a large scale, the researchers want to conduct a large FDA phase-III clinical trial to discern the long term benefits of the diet.

“This study provides evidence that people can experience significant health benefits through a periodic, fasting-mimicking diet that is designed to act on the aging process,” Longo said. “Prior studies have indicated a range of health benefits in mice, but this is the first randomized clinical trial with enough participants to demonstrate that the diet is feasible, effective and safe for humans.

“Larger FDA studies are necessary to confirm its effects on disease prevention and treatment,” he said.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The News-Letter.