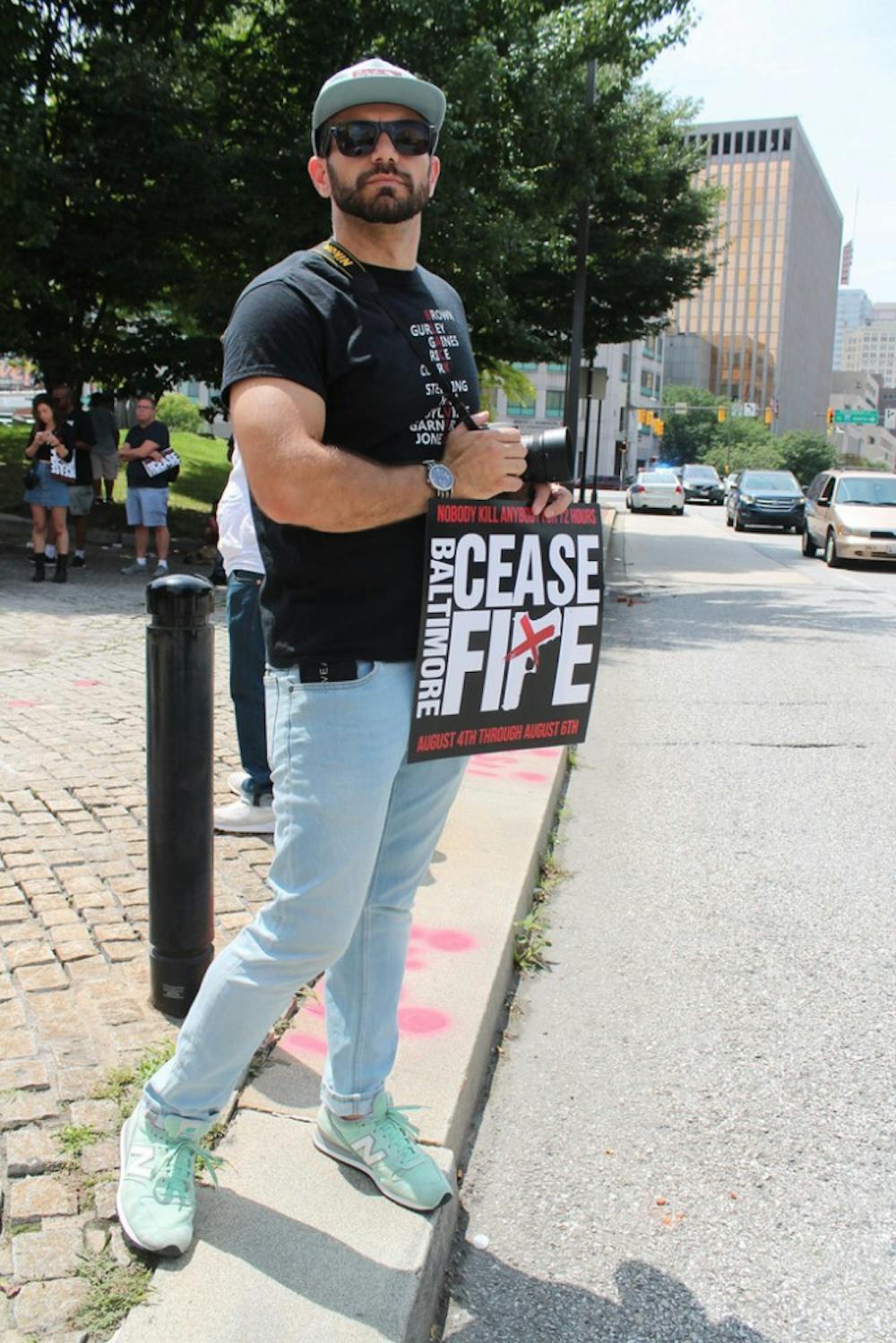

Baltimore Ceasefire 365 celebrated its first anniversary this August. The anti-violence organization was created to encourage Baltimore citizens to decrease gun violence in the City through the hosting and promotion of Ceasefire weekends four times a year. During this past Ceasefire weekend, the City went 41 hours without a shooting.

According to The Baltimore Sun, the City has, on average, more than a murder a day.

Erricka Bridgeford, a Baltimore resident, is the founder and co-organizer of the Ceasefire movement. During the Ceasefire Weekends, Bridgeford works with locals to guarantee that certain zones of the City will remain murder-free.

Sophomore Bentley Addison was introduced to the movement through the Community Impacts Internship program (CIIP) at the Center for Social Concern. For his internship, Addison worked with the 29th Street Community Center, a partner of Ceasefire, which holds events during Ceasefire Weekends. Addison heard many stories of violence over the course of his summer internship. Because of this, he has become a supporter of the Ceasefire movement.

“We have youth workers who’ve lost family members, friends, cousins, all to violence in Baltimore City,” he said. “That’s the reason why I think Ceasefire is such a great movement. It’s trying to end this cycle.”

According to the Baltimore Homicides map, published by The Baltimore Sun, the area directly around the University has been murder-free in 2018. However, Addison believes that the homicide rate in Baltimore is an issue Hopkins students should care about as members of the Baltimore community.

Kent Abdullah, a member of the Baltimore community and a criminal defense specialist at a juvenile and family services center in Baltimore, emphasized the importance of a stable family in violence prevention.

“With these youngsters, they are more than likely from violent homes. So we don’t just reach out to the individuals, we reach out to the families,” Abdullah said. “Not all cases are the same. But, we encourage them to think positive, to seek employment, to further their education.”

Abdullah also works with the Ceasefire movement by hosting violence prevention workshops which are open to the community. As a criminal defense specialist, his goal is to reduce sentences and prevent future incarcerations through community interactions.

“We go out and spend time with the community. We give time to at-risk individuals. Our job is to try to reverse the cycle, to de-program it,” Abdullah said.

Abdullah thinks that it will take a long time to meaningfully reduce crime.

“Everybody thinks it’s the weekends, but it’s really [about] the 365 days of ceasefire,” he said. “Crime doesn’t stop on the third, fourth or fifth. It’s an ongoing process that we’ll have to do throughout the years.

Addison agreed, emphasizing the need for public health solutions beyond the Ceasefire movement.

“It’s simply unrealistic to expect what is a public health problem to go away without public health solutions,” Addison said. “What we have to do going forward, is to implement public health solutions.”

Abdullah went on to speak about the goals of the Ceasefire Weekend.

“If we can save one person’s life, that would be the goal. But the most important goal is to bring peace and justice throughout the community,” he said. “Let them know that there are options and life other than crime.”

Klaus Philipsen, author of Baltimore: Reinventing an Industrial Legacy City, explained that Baltimore’s Ceasefire movement is not unique and is modelled after other cities’ movements.

Boston’s Operation Ceasefire is a government-led program which aims to procedurally remove gangs and gun violence from the city. Contrarily, Baltimore’s Ceasefire movement is more of a grassroots movement.

Like Abdullah, Philipsen sees family life as a source of criminal behavior. He spoke specifically about the children from families impacted by poverty or other social problems.

“They don’t learn the basic values that life is precious, or to delay your own interest or to negotiate,” Philipsen said. “They need basic skills of how people can live with each other [which are] taken for granted by the more privileged folk.”

The 2017 U.S. Census states that 23.1 percent of Baltimore residents live in poverty, which is almost twice the national average. Philipsen believes that there is a link between systemic injustices and violence.

“Baltimore has so many systemic injustices, inequality and inequity issues that too many people are left out from participating in what makes a community,” he said. “They have no upside.”

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The News-Letter.