The dour and gloomy atmosphere that keeps Homewood in a depressing stasis is all too familiar to your average Hopkins student — or maybe just the cynical ones. Fortunately, this environment is unique in Baltimore, a city that maintains its vibrance in spite of everything. So when one wants to escape the heavy-hand of academic insecurity and imagined doom, it is easier than they might assume to find refuge in what seems like a whole different world.

Enter Hampdenfest, the annual neighborhood party hosted by one of Baltimore’s most bizarre and, sadly, most rapidly gentrifying locale. Held this year on Saturday, Sept. 9, Hampdenfest showcased the neighborhood’s small businesses and its mixed population of hipsters, John Waters extras and working class people.

Not to be confused with Honfest, which is more of a largely white Baltimorean celebration of beehive hairdos and the city’s unique dialect, Hampdenfest is essentially a gentrification party. Whether this is good or bad is up to you, but it is worth noting that not so long ago the neighborhood was a stronghold of the white working class.

Hampden, like so many neighborhoods in major American cities, went from being very poor to being increasingly affluent as small businesses and artists moved in. In 2005 the Baltimore Sun reported that housing prices in Hampden had doubled.

That article painted a somewhat bleak picture of a changing neighborhood, describing a closed thrift store, “where a sign blaming the neighborhood’s ‘gentrification’ for its closure screams out from a shuttered storefront.”

Today the old neighborhood continues to recede as more boutique shops and restaurants move in. On one hand the influx of business has made Hampden more attractive to people willing to spend money — like maybe some affluent college students who live nearby. While that is no doubt good, gentrification is ultimately a destructive force: out with the old, in with the new.

Perspectives differ, but the Hampden Village Merchants Association (HVMA), which is a lead organizer of Hampdenfest, lauds the changes. The HVMA states on their website that, “Over the past several decades, Hampden has reinvented itself as a thriving community of independent and locally-owned businesses. The [cotton] mills have been repurposed as living spaces, offices, artists studios, restaurants, and more.”

The neighborhood certainly is home to some of the best restaurants and shops in the city, drawing in the increasing number of tourists that we apparently get around here. Businesses in Hampden’s commercial heart — West 36th St. or “The Avenue” — are almost entirely locally owned and operated. Because of this, Hampden remains uniquely Baltimorean, albeit in a different way than it used to be, and the annual Hampdenfest is still a celebration of part of what makes this city great.

Being Baltimore, Hampdenfest is hardly your average block party. Key to the festivities were the toilet races, which is basically people riding down a hill on elaborately decorated wheeled toilets. Vendors from both Hampden and other parts of Baltimore set up shop on West 36th St., selling the sort of endearing and homegrown goods that define the contemporary artisanal economy. Alongside all that commerce and bathroom athletics, local bands played to crowds at three stages spread across the street.

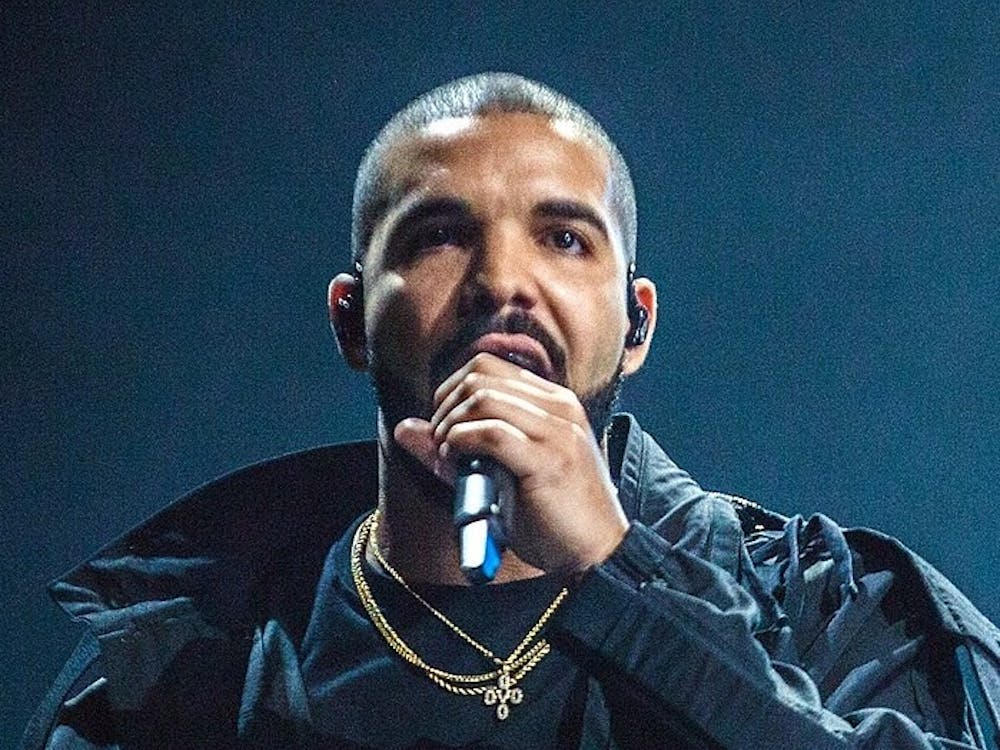

This year the rapper/producer team Bond St. District, comprised of emcee DDm and producer Paul Hutson, headlined the festival, accompanied by an eclectic mix of bands. Baltimore bands can be difficult to define with genres. Suffice to say there were plenty of good local bands — Raindeer, PLRLS and Canker Blossom to name a few — and good music. Indeed, public festivals like Hampdenfest are integral to the promotion of the city’s diverse music scene, particularly when they celebrate artists like DDm, who is black and identifies as gay.

Hampdenfest as an event seems to have a particular appeal to the Hopkins community. For one, it’s early in the year, so students can attend without the crushing weight of stress and hopelessness weighing down on them. Second, you can walk to it. Finally, the festival and Hampden itself is a healthy escape from the Hopkins bubble that so many unfortunately live their lives in.

While the neighborhood and much of the city is no longer what it used to be, it is still fundamentally Baltimore, something which Homewood and indeed many of the spaces controlled by the University arguably are not.

The festival is, if anything, an exploratory opportunity for the Hopkins community. Beyond the bubble is a city, a city that’s changing for better and for worse.

With that change, though, can come at least one opportunity — in this case an opportunity to interact with a place so often portrayed as being one dimensional. Hampdenfest is hardly a cross-section of the city, but following some of the paths that converge on W. 36th Street one weekend in September can lead one to another side of Baltimore.

Through a rapper like DDm, a fan can discover the movement that is Baltimore hip-hop: Young Moose, Lor Scoota, Tate Kobang, Jay IDK, Creek Boyz and on, all voices of another side of the city.

In the food offered at the festival’s stalls or even just in Hampden’s many restaurants, one can begin their hunt for more and better cuisine: like the vegan soul food of The Land of Kush, a black-owned business in Upton, to the simple Mexican meals at Tortilleria Sinaloa in the predominantly Hispanic section of Fells Point.

From the galleries of Hampden to the vendors on the Avenue, one can reach into a vibrant art scene defined by small, eclectic galleries catering to every taste and background; out of the bookstores and into a revolutionary literary culture led by young people of color.

Failing all that, the parties and festivals that every bar, club and public venue in Baltimore throws year round (usually every weekend) are worth going to. As far as the toilet race goes, that’s just good entertainment.

Dwight Watkins, who is probably the city’s foremost living writer and a voice of the Baltimore that exists for many only in platitudes and soundbites about the war on crime, once wrote, “I’m lost in this city. This isn’t the place I grew up in.” His words are conscious of what gentrification can do to a city like this, with poor people — usually people of color — left behind as change sweeps through.

So get to know Hampden, but understand that Baltimore is a city of blocks, each different from the next, and while becoming familiar with one through a celebration of what makes it unique is a good start, it is just that: a start.

Hampden, what it was and what is now, is part of Baltimore, just like every neighborhood in the city — from Fells Point to Sandtown, the Inner Harbor to Mondawmin.

Neighborhoods, gentrified or otherwise, make up Baltimore. The Baltimore that D. Watkins writes about, where people of color struggle to survive in a world that’s failed them, is inseparable from the fine dining and boutique stores of The Avenue. No painting is one brush stroke; No city is one block. So Hampdenfest is an invitation to get to know Baltimore, with the caveat that one should be conscious that Hampden might be Baltimore, but Baltimore is not Hampden.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The News-Letter.