By MEGAN CALLANAN For The News-Letter

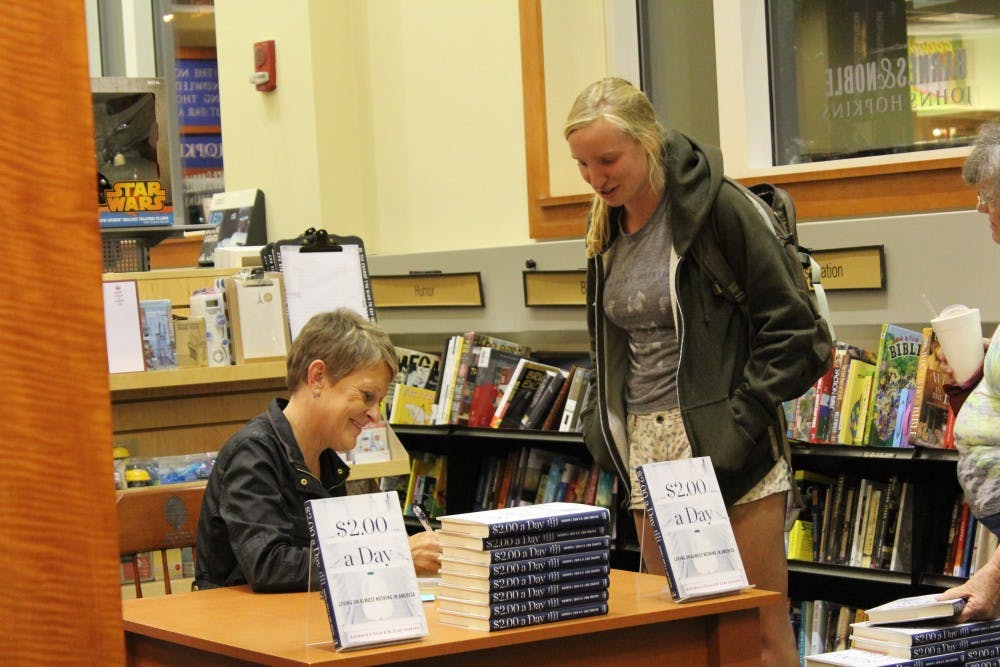

Sociology professor Kathryn Edin discussed her new book, $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America at Barnes & Noble on Tuesday with students and community members.

The book’s title came from the international poverty line of $2.00 day, a value that was calculated to quantify global poverty and is used by the U.S. government as well. It includes anything a family has told the census bureau about their cash holdings and their income.

Edin began her research before the welfare reform of the 1990s, when 68 percent of low-income Americans were receiving welfare, asking single mothers on welfare about their expenses.

She then transitioned to studying families and low-income working Americans. Her work in the summer of 2010 that followed young adults born into public housing in Baltimore led her to leave her post at Harvard to join the Hopkins faculty.

Her work led to two questions: Was it possible that in the aftermath of welfare reform a new form of poverty had emerged? And was it possible that in the context of America, there was something about cash that was essential to survival?

Edin said that welfare reform has allowed society to provide programs such as food stamps and medical care.

“[It has] transformed our safety net from cash to ‘in-kind resources’ such as food stamps and medical care,” she said. In-kind resources are those that provide physical services.

Edin and her team discovered that there are 3.4 million children living in households with virtually no cash flow for at least three months of the year. In these households, only 10 percent of parents receive welfare.

“[They are] workers who are hanging on to the ragged edge of a labor market that is increasingly punishing and degrading,” Edin said.

One million Americans today receive welfare, and 500,000 of them reside in New York or California, leaving many states with almost no welfare safety net.

Edin received a variety of responses when she asked those who may qualify for welfare benefits why they hadn’t gone on the program. Some people didn’t know what welfare was, and others believed it was hard to qualify. A welfare office employee told an individual to come back next year due to a surplus of needy people in Ohio.

She explained that if states don't use welfare money, they can use it for other programs. Two thirds of funds are diverted this way.

Edin shared anecdotes from her field work including common methods that those living under the poverty line resorted to in order to get cash, such as selling blood plasma and selling food stamps, all to enable themselves to pay for vital necessities.

Edin noted a positive element of the system: In almost every household at least one person had health insurance, which many low-income Americans still cannot afford even after the passing of the Affordable Care Act.

She found that many of the people she interviewed described work as therapeutic, yet the current system of employment is hard on low-income workers, who are often fired after missing just one day of work, even if illness or disability interferes, according to Edin. Edin advocated for an expansion of work opportunity.

“[I am] optimistic about the power of work to change lives,” she said. “Work brings dignity, a sense of citizenship and a sense of civil engagement.”

While many people argue that work is part of the problem with the welfare system, often called “workfare,” Edin argued that work is part of the solution.

She then opened the floor to questions. One student questioned how Edin could perform research of a seemingly depressive nature.

“If my story can even help one person like me, my suffering will be worth it,” Edin said.

She also cited the positive spirit of children as another factor that helps her stay positive when researching. Sophomore Kyra Meko explained she enjoyed this portion of the talk.

“I found this part of Edin’s talk to be particularly powerful,” Meko said. “While she portrays the acute suffering of these many Americans, she is also able to give the situation a sense of hope.”

After the talk concluded, Edin signed books for the audience members. On the way out, many students discussed with each other what they thought of Edin’s message.

Katherine Hamlet, a graduate student in the Bloomberg School of Public Health, looked at the talk through the lens of public health studies.

“She focused a lot on this as an issue that needs to be treated,” she said. “I like to also look at the side of prevention, and I think that is a topic that should be addressed to keep [low-income Americans] from getting to that point.”

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The News-Letter.