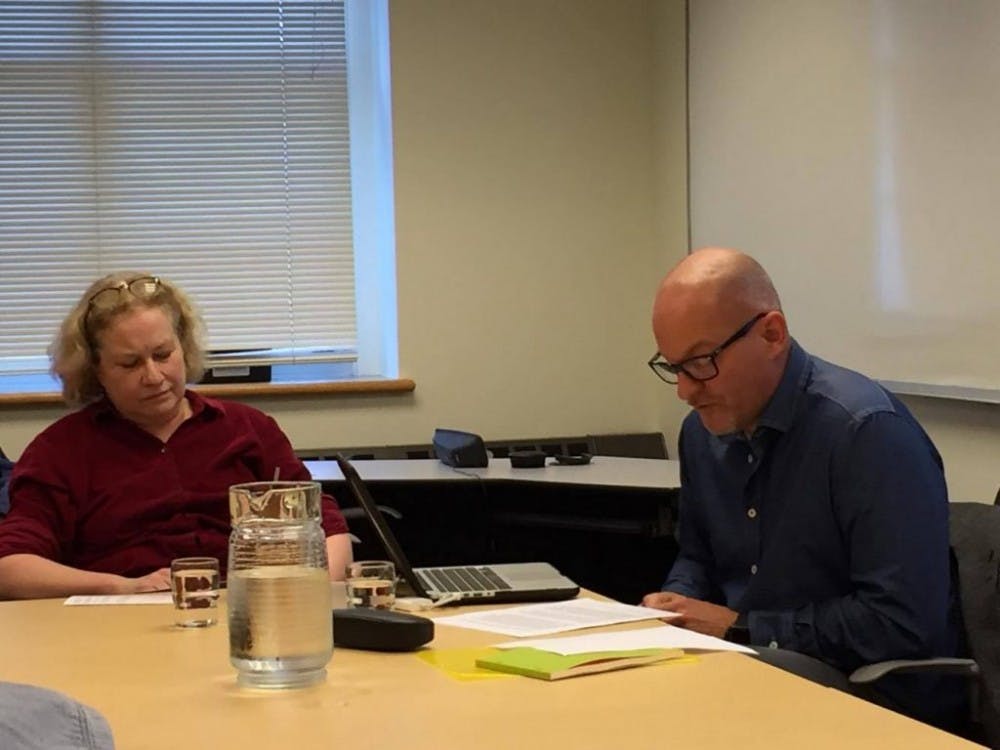

Nils Bubandt, professor at Aarhus University in Denmark, gave a talk titled “The Passing of Paradise: Corals and The(ir) End in West Papua” as part of the Critical Climate Thinking Lecture Series on Tuesday afternoon.

Sponsored by the Alexander Grass Humanities Institute and co-sponsored by the departments of Anthropology and German and Romance Languages and Literature, it was the second talk of the series this semester.

Bubandt has written papers on a wide range of subjects, including witchcraft in Indonesia, Islam and Sufism, Muslim-Christian conflicts and the Anthropocene, the term that refers to the current period in which humans dominate the environment.

“I will take it upon myself to be the eternal amateur,” Bubandt said. “Somebody who loves the world and is curious about finding something new.”

He began with discussing what drew him to coral.

“Corals are charismatic assemblages of life,” he said. “Anyone who has snorkeled or dived in a tropical coral reef can attest to this. They’re kind of alive with a tentacular curiosity that for me is enthralling.”

His talk, he said, was about the “tentacular charisma of coral” and its ability to build heterogeneous assemblages of life and symbiotic relations across multiple borders. These borders, he said, included the borders that separate species, humans of the global north from those of the global south and humans from spirits.

He emphasized the crossing of epistemological borders separating different branches of study, such as natural science from human science, biology from anthropology and religion from conservation.

“I’m attracted to coral because they seem to generate hope, worry, wonder and concern in equal measure,” he said. “Coral for me is a way of doing anthropology in and out of the Anthropocene. I am interested in tracing the overlaps of involutionary thinking in the millenarian movements and the biological understanding of coral.”

He described coral as figurations: creatures of fact and fiction that symbolize and embody social and scientific tensions, trends and transformations. He then proceeded to lay out three kinds of temporal thinking following through coral figurations: utopian, apocalyptic and millenarian.

“Millenarian temporality is the promise of a unfulfilled past, the return of a past that never was,” he said.

In exploring what he called coral millenarianism, he recounted his experiences with a 70-year-old Filipino man called Yesus In, who lives in a village in Bantayan Island. According to some people there, he is Jesus Christ.

“Much about this man flies in the face of good behavior,” Bubandt said. “He smokes, drinks inordinately and when drunk he offers roams the village swearing, cursing and yelling. The darkness of many nights in the village is often broken by the voice of Yesus In yelling at people to bring him more liquor, shouting at his dead ancestors to stop bothering him and walking along the beach wailing for his mother, the Virgin Mary.”

In honor of the Virgin Mary, In collects coral and arranges them on his porch in the shape of flower bouquets, tying them with a piece of string. In In’s view, corals are the flowers of the Virgin Mary.

“According to a prophecy that is widespread in the area, the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus, is seated in the coralline underwater gardens of Raja Ampat,” Bubandt said.

In discussing the second branch of temporal thinking, coral utopia, he began with outlining the progression of tourism in Raja Ampat, which brands its coral gardens as the “Last Paradise on Earth.”

“It’s true that growth in tourism in Raja Ampat has been phenomenal,” he said. “Though now, this tourist economy is being stretched beyond its ecological carrying capacity. Just last month, one of the big tourist yachts barreled into one of the coral reefs and destroyed a large area. But it still builds on the utopia of ecotourism.”

The final figuration, coral apocalypse, refers to the way the decline of coral reefs comes hand in hand with the decline of the globe.

“Increasingly, the future of the world has become unthinkable in terms other than apocalyptic,” he said. “Few other assemblages of life are becoming clearer examples or figurations of apocalypse than the tropical coral reef.”

The coral reef, he said, is the world’s most symbiotic ecosystem.

“What is interesting is the density of the symbiosis at stake here,” he said. “Between five and 50 million dinoflagellate cells crowd together on every square centimeter of coral pollen.”

He explained the relevance of involution to coral reefs.

“Corals are beings that live and die in multispecies coordination in which otherness is integral,” he said. “This is the source of the magic, the otherness within, of intimate involution.”

Graduate student Maya Ratnam commented on the new perspective the talk provided.

“All this super imaginative work is being done underwater, in the air, on creatures that are pretty far removed from human beings, and I think that’s really interesting to see how all this stuff is being invited into a discipline which has traditionally been about humans and human problems,” Ratnam said.

Ratnam described why she enjoys the climate lecture series, especially in the context of the changing environment.

“Now realizing that our problems are extending, causing problems in the world, causing ecological problems and that we have to theorize about that seriously, is what I found really fascinating about these kind of talks and the climate series,” she said.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The News-Letter.