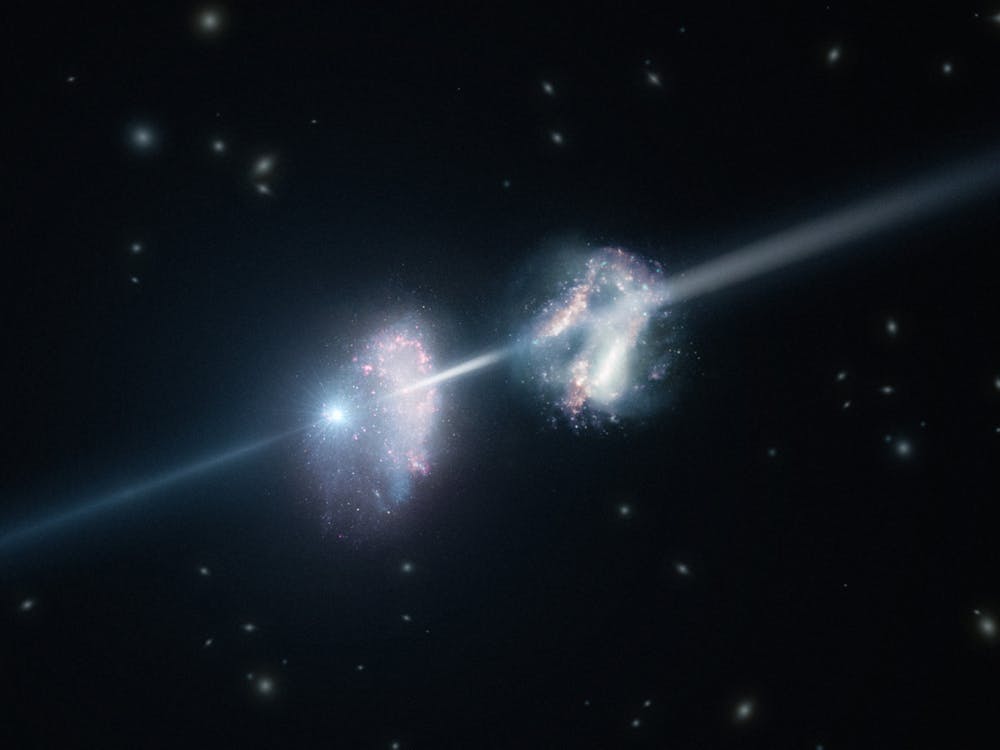

Researchers at California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, Calif. have recently discovered evidence of “Planet Nine,” a giant planet located at the outer edges of the solar system.

Planet Nine has a bizarre and highly elongated orbit, and it orbits about 20 times farther from the sun on average than Neptune. This means that it would take 10,000 to 20,000 years for the new planet to make one full orbit around the sun. It has a mass about 10 times that of Earth.

“This would be a real ninth planet,” Mike Brown, one of the head professors on the research team, said. “There have only been two true planets discovered since ancient times and this would be a third. It’s a pretty substantial chunk of our solar system that’s still out there to be found, which is pretty exciting.”

Brown, along with fellow Caltech researcher Konstantin Batygin, discovered the planet using mathematical modeling and computer simulations. However, the team has not yet been able to observe the object directly. The two researchers published their work in the Astronomical Journal. One key idea addressed in their article was how Planet Nine helps to explain a number of mysterious features of the Kuiper Belt, a expanse of icy debris located beyond Neptune.

“Although we were initially quite skeptical that this planet could exist, as we continued to investigate its orbit and what it would mean for the outer solar system, we become increasingly convinced that it is out there,” Batygin said. “For the first time in over 150 years there is solid evidence that the solar system’s planetary census is incomplete.”

Brown noted that, because this planet is 5,000 times the mass of Pluto, there should be no debate over whether it constitutes a true planet. Brown adds that Planet Nine is certainty not a dwarf planet since it gravitationally dominates its neighbors in its region of the solar system. In fact, this planet dominates a region larger than any of the other eight planets.

The path leading to this theoretical discovery began in 2014 when Chad Trujillo, a former postdoctoral student working with Brown, published a paper noting the similarity among the obscure orbits of 13 distant objects in the Kuiper Belt. Trujillo proposed that the presence of a small planet present could explain these obscure orbits.

Soon after Trujillo published his paper, Batygin and Brown realized that six of the 13 objects that Trujillo studied follow elliptical orbits pointing in the same direction.

“It’s almost like having six hands on a clock all moving at different rates and, when you happen to look up, they’re all in exactly the same place,” Brown said in a Caltech press release.

According to Brown, the odds of having that happen are something like 1 in 100. But on top of that, the orbits of the six objects are also all tilted in the same way: pointing about 30 degrees downward in the same direction relative to the plane of the eight known planets. The probability of that happening is about 0.007 percent.

“Basically it shouldn’t happen randomly,” Brown said. “So we thought something else must be shaping these orbits.”

Brown and Batygin first investigated the idea that there were many Kuiper Belt objects that, together, exerted the gravity needed to keep the subpopulation together. However, this hypothesis was ruled out because it would require the Kuiper Belt to have about 100 times the mass it has today. The two researchers then explored the possibility of a planet. They noticed that if they ran simulations using a massive planet in an anti-aligned orbit, the Kuiper Belt objects followed the elliptical orbits observed.

They went on to discover that Planet Nine’s existence helps explain more than just the alignment of the Kuiper Belt objects. Using the simulations, the researchers also predicted that there would be objects in the Kuiper Belt on orbits inclined perpendicularly to the plane of the planets. Batygin had, in fact, discovered such orbits over the last three years.

Both Batygin and Brown are continuing to refine simulations to learn more about Planet Nine’s influence on the solar system. The scientists are also making an attempt to find the planet in the skies.

“I would love to find it,” Brown said. “But I’d also be perfectly happy if someone else found it. That is why we’re publishing this paper. We hope that other people are going to get inspired and start searching.”

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The News-Letter.