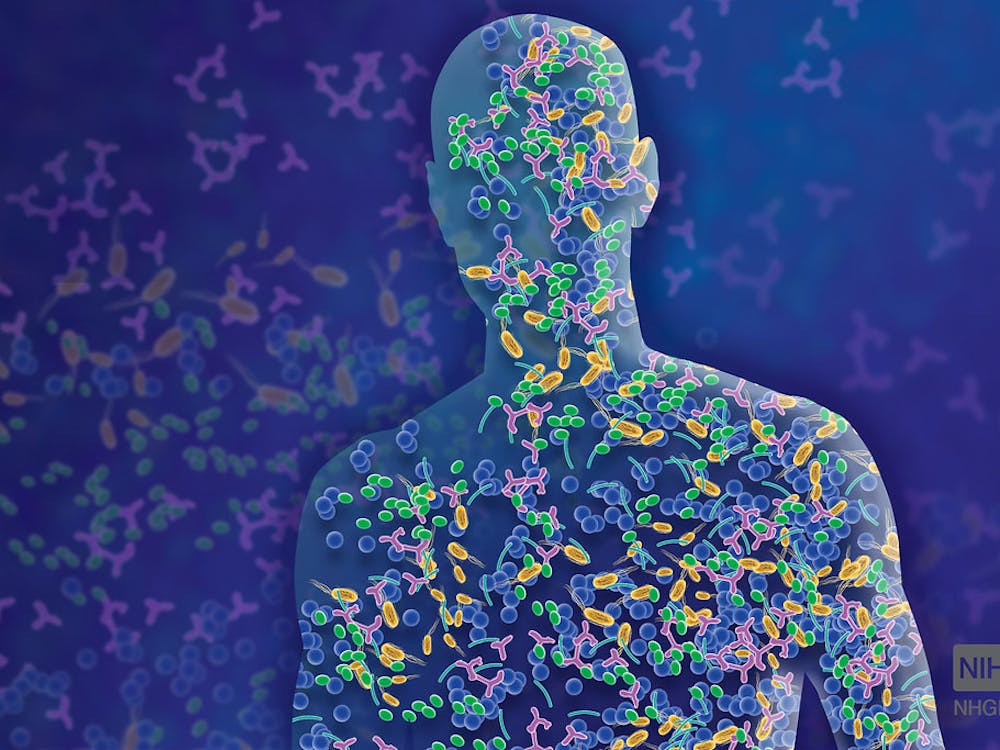

On every medical form, there is that one box to check off: “allergies.” It’s a question that most people are lucky enough to gloss over, but allergies are a very real problem in the United States and the world, especially among children. It is estimated that between two percent and 10 percent of children in the world are afflicted with food allergies.

Scientists have long suspected that one of the many causes of these allergies is genetic: An allergic reaction may be shared among several children in a family, or be passed from parents to children.

But several researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, in a study of the human genome, have pinpointed the exact genes associated with peanut allergies.

Dr. Xiaobin Wang was the principal investigator of the study published by Hopkins researchers in the scientific journal Nature Communications. During their study of the genome, Wang and her team analyzed DNA from over 2,700 patients, including 1,315 children and 1,444 of their parents. In particular, they focused on analyzing subtypes of some of the allergies that are more common and well-defined, including peanut, milk and egg allergies.

What they found was a specific locus in the genome associated with increased risk of a peanut allergy. The HLA-DR and HLA-DQ gene region of the human genome consistently had mutations in patients with peanut allergies. The significance of this finding is that it is one of the first genes conclusively associated with a certain food allergy. Though there has been speculation in the past, Wang’s research provides convincing evidence of a genetic basis to allergies.

Although Wang’s lab may have found a certain mutation in a specific gene associated with the peanut allergy, not all of those possessing the mutation had the allergy. The answer to this conundrum is epigenetics, when factors other than the DNA itself influence gene expression. DNA methylation, one of these processes can dictate if a gene is expressed at all; those who have the mutation but have fortunate epigenetics could still experience no allergies.

Researchers have also begun to discover ways of remedying food allergies. In a study led by Gideon Lack of King’s College London published in The New England Journal of Medicine, researchers discovered that peanut consumption during infancy led to overall lower rates of peanut allergies later in childhood. The study was conducted across genetically similar populations of Jewish children living in Israel and the United Kingdom. The Israeli children were naturally exposed to higher levels of peanut consumption during early childhood.

When the researchers brought their findings to the lab to test, they gave two diets out to children highly susceptible to allergies: one avoiding peanuts altogether and one including it regularly. Those who ate them regularly were seen to have an 81 percent decrease in allergy.

Such notable scientific findings in such close temporal proximity have great implications for how doctors and patients may handle allergies in the future. The discovery of a genetic basis is the first step to a cure. The knowledge that early exposure of allergens in high-risk children may alleviate symptoms provides a promising pragmatic treatment for food allergies in the near future.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The News-Letter.