The Baltimore Museum of Art has a new featured exhibition entitled “Max Weber: Bringing Paris to New York” as part of its contemporary art collection.

Max Weber (1881-1961) was a Russian-American artist who rose to fame in the early twentieth century as a revolutionary, avant-garde, visual artist.

His energetic style often blended traditional influences with more modern techniques that brought about noticeable change and sparked debate in the art world.

Weber’s first interaction with modern art was in 1905 when he left the United States and traveled to Paris, France.

It was there that he interacted with and studied with modern art legends Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, attended the Académie Julian and presented his work at major exhibitions such as the Salon d’Automne and the Salon des Indépendents.

Upon Weber’s return to the United States in 1909, he applied many modern techniques he learned from his contemporaries and became a pioneer in Cubism, wherein subjects are often broken up into a new and imperfect manner so as to be analyzed from many different perspectives. Weber began experimenting with distortion and color usage to bring his art to life.

The first room of the exhibition was heavily adorned with Weber’s finest figure drawings.

Each example shows how Weber re-imagined the human body, something that past artists have tried to perfect in their paintings, and portrayed it as an imperfect figure that can be broken down into a series of lines and enhanced with color.

For instance, “The Apollo in Matisse’s Studio” is a very colorful and dynamic painting that rethinks the male form as fluid, comprised of the intersection of many lines.

The dominant colors of lavender and green pay tribute to Matisse’s random color usage and plays with the concept of complementary colors as a tool for bringing out the cohesiveness of the overall work.

Similarly, “Female Nude No. 4” features an androgynous-looking figure, possibly to suggest that male and female forms have more similarities than differences.

The woman’s pale figure is deformed and imperfect and surrounded by a choppy band of deep, hunter green, making her skin tone and piercing dark eyes pop out to the viewer.

Weber did paint other subjects other than male and female nudes.

His “Still Life” of a collection of fruit on a table plays with perspective and optical illusions.

Its altered geometrical space and sharp outline of each element on the table give rigidity and complexity to an otherwise simple scene comprised of curvy and supple materials.

Additionally, “Avoirdupois” is a challenging, abstract and very Cubist work.

It has a Picasso-esque style in that it is a broken-up, shattered image of incomprehensible words and symbols.

It is unclear whether this scene belongs in reality or fantasy or what its true message really is, but it is clear that Max Weber was very much interested in exploring issues of space and rethinking the world and everything in it as very imperfect, challenging and wonderfully confusing.

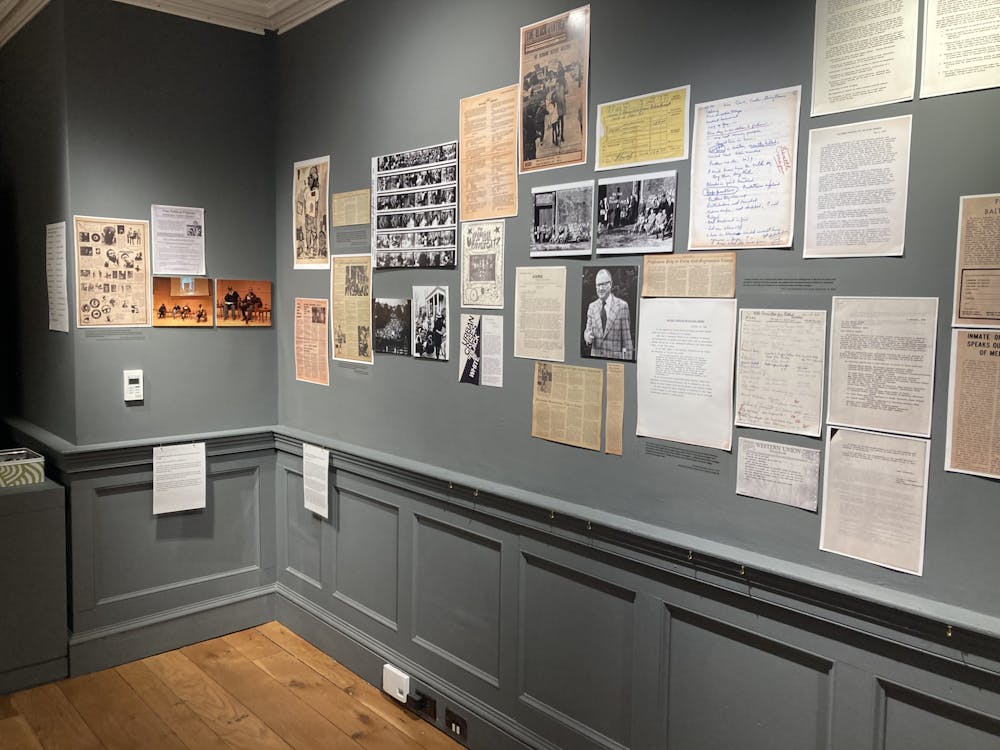

It is commendable that the Baltimore Museum of Art chose to feature a diverse array of Weber’s personal artwork, ranging from sketches to paintings to even small sculptures and notebooks. The exhibition does a good job of tracing Weber’s personal history and giving a detailed, historical context from Weber’s sojourn in Paris to his eventual return to New York City.

It is also helpful to the viewer to witness Weber’s work in the company of other modern paintings. Right next to the exhibition is a plethora of landmark works by Kirchner, Beckmann, Picasso, and Matisse, whose abstract styles help clarify the artistic direction that Weber chose to go in.

The only drawbacks are that the exhibition is quite small and the curators make an uncreative use of space.

For a featured exhibition such as this, it is a shame that it is only housed in two, moderately-sized rooms. Weber was such a dynamic, groundbreaking artist who produced very unique artwork, so the fact that that viewers are limited to such a small amount of space is disadvantageous.

Finally, it is odd that the very unusual and spatially distortive work of Weber is mounted on the walls in a very traditional manner. Instead of playing with every inch of space as Weber did, the curators chose to display the paintings and drawings in a predictable way, on a plain wall at eye level. Perhaps hanging paintings at different heights or at different angles would have complemented their spatial awkwardness more.

“Max Weber: Bringing Paris to New York” is free of charge and runs through June 23, 2013.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The News-Letter.